SCORES & OUTDOORS: Lady bug, lady bug, fly away home…

by Roland D. Hallee

by Roland D. Hallee

That is the beginning of the popular child’s rhyme about lady bugs. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Many years ago, when our kids were growing up, we did a lot of camping in our popup camper. Every year, after the campgrounds closed, usually on Columbus Day weekend, we would take our “last picnic of the year.”

Last week, our daughter called and wanted to do that again. It was a little strange request seeing that she is 48 years old. Maybe it was the anticipation of the empty nest syndrome seeing that her youngest child is a senior at Waterville High School, and will be leaving after the school year to pursue her education.

So, my wife and I agreed. It was just a matter of where we would go with limited time on our hands. We decided on Blueberry Hill, in Mt. Vermon. From there, we could have our picnic, and take in the brilliant foliage from that vantage point. Looking east, you can see Great Pond and Long Pond, along with miles and miles of colorful fall leaves.

While there, we were infested with lady bugs. They were swarming around us, landing everywhere on us. As we tried to flick them off more would come. As we were leaving, they also were inside the car.

We finally decided to go to Lemieux’ Orchard, in North Vassalboro. My wife wanted to make an apple pie for our trip to Vermont this coming weekend, and some homemade apple sauce.

While there, the lady bugs made their appearance. They were everywhere, also. I ran into an old friend and we began talking. He also commented on the lady bugs.

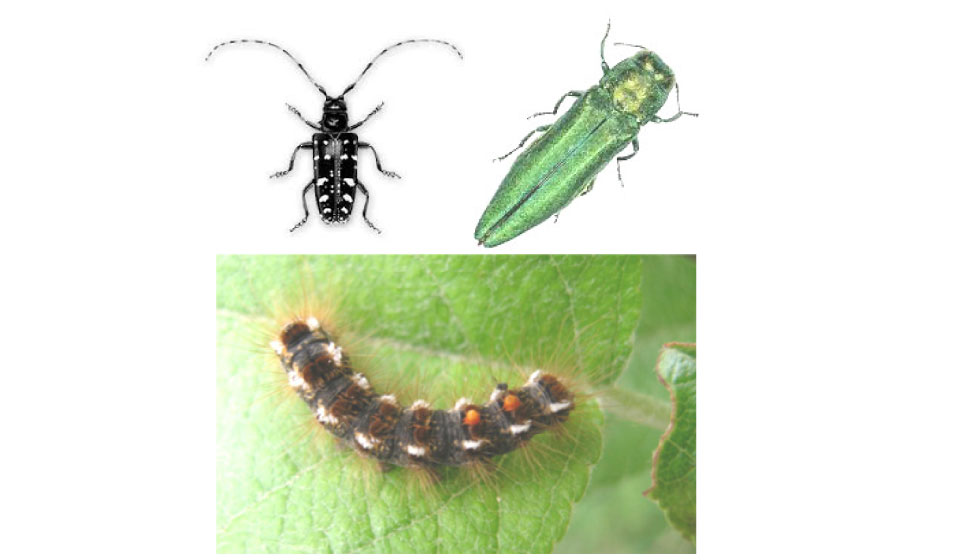

The family is commonly known as lady bugs in North America, and ladybirds in Britain. Entomologists prefer the name ladybird beetles as these insects are not classified as true bugs.

The majority are generally considered useful insects, because many species prey on herbivorous insects such as aphids or scale insects, which are agricultural pests. The lady bug, or ladybirds, are only minor agricultural pests, eating the leaves of grain, potatoes, beans and various other crops, but their numbers can increase explosively in years when their natural enemies, such as parasitoid wasps that attack their eggs, are few. In such situations, they can do major crop damage. They occur in practically all the major crop-producing regions of temperate and tropical countries.

The lady bugs usually begin to appear indoors in the autumn when they leave their summer feeding sites in fields, forests and yards, and search out places to spend the winter. Typically, when temperatures warm to the mid-60s F, in the late afternoon, following a period of cooler weather, they will swarm onto or into buildings illuminated by the sun. Swarms fly to buildings in September through November depending on location and weather conditions. Homes or other buildings near fields or woods are particularly prone to infestation.

A common myth, totally unfounded, is that the number of spots on the insect’s back indicates its age. In fact, the underlying pattern and coloration are determined by the species and genetics of the beetle, and develop as the insect matures. In some species its appearance is fixed by the time it emerges from its pupa, though in most it may take some days for the color of the adult beetle to mature and stabilize.

The harlequin ladybird, is an example of how an animal might be partly welcome and partly harmful. It was introduced into North American, from Asia, in 1916 to control aphids, but is now the most common species, out-competing many of the native species. It has since spread to much of western Europe, reaching the United Kingdom in 2004. It has become something of a domestic and agricultural pest in some regions, and gives cause for ecological concern. It has similarly arrived in parts of Africa, where it has proved unwelcome, perhaps most prominently in vine-related crops.

It does explain something, maybe. As we have discussed before, toward the end of the summer, particularly in September, we were inundated with parasitoid wasps at camp, and saw no lady bugs. On Blueberry Hill, we saw plenty of lady bugs, but no wasps. We have yet to see a lady bug in our house this fall.

So, what about that rhyme? Here goes:

Lady bug, lady bug, fly away home;

Your house is on fire and your children are gone;

All except one, and that’s Little Anne;

For she has crept under the warming pan.

Roland’s trivia question of the week:

Of the four remaining teams in the MLB playoffs, which team has never won a World Series?