SCORES & OUTDOORS: The bug and the tree

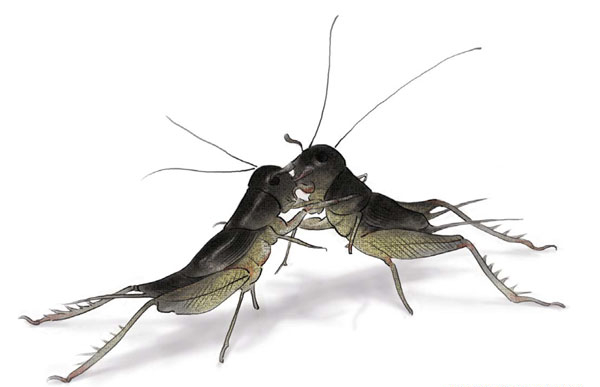

The boxelder bug

by Roland D. Hallee

by Roland D. Hallee

There they were! Marching along the railing of my porch as my wife and I were enjoying the day’s end of sunshine on a Saturday afternoon. They formed a column like a trucking convoy, one behind the other, all heading in the same direction. Blackish-colored bugs with red stripes, about a half inch long. I had seen them before, but not this many.

Then, it happened! The next morning, one had found its way into the house, clinging to the outside door, trying to make its best impression of an opossum. Playing dead, not moving.

It was time to find what these things were and why were they trying to enter our domain.

It really didn’t come clear to me until a little later, when evidence started to fall into place. First was a call out to my contact, Allison Kanoti, acting state entomologist, with the Maine Forest Service. But, it was the weekend, and I would have to wait until mid-week for an answer.

Second, I met with an arborist with the plan to cut down some dead trees on my property. The arborist informed me the trees were boxelders, and would have not much heating value. (That was OK, I just wanted to get rid of them.)

Then came the news from my state contact: the bugs were most likely boxelder bugs. Ta-dah! There is the connection.

Boxelder trees and boxelder bugs

The boxelder bugs feed almost entirely on boxelder, maple and ash trees. Another clue. I have a maple tree directly in front of my porch.

These bugs also like to winter indoors, if possible. Should they enter your home, they will hibernate there, mostly in cracks in window frames, gaps and crevices, and tears in screen doors. But, once they get in your home, they will lay dormant while the weather is cool. Once your heating system becomes active, they falsely perceive that it is spring time and they will head out in search of food. Their extracts may stain upholstery, carpets, drapes, and they may feed on certain types of house plants.

The next question: do they bite?

They are not typically known as biters, but they have the ability to pierce into skin, which makes the skin a bit irritated and results in a red spot that resembles a mosquito bite. Medical attention should be sought in the case of a bite. They are, in general, harmless to humans and pets.

These bugs are not classified as agricultural pests and generally are no danger to ornamental plantings. They are, however, known to do damage to some fruits in the fall as they leave their summer homes in trees to seek areas to overwinter.

The boxelder bug, Boisea trivittata, emits a strong scent, similar to stink bugs, should they be disturbed or threatened. Spiders are their minor predators, but because of their defense mechanism, only a few birds or other animals will eat them.

Eggs are laid by females in the cracks of tree bark during spring. They prefer female boxelder trees, which produce seeds, as opposed to male trees that do not.

Boxelder bugs prefer seeds but will also suck leaves. They are frequently seen on maple trees as these trees provide them with seeds as well.

So, the arborist is coming in a week or so to take down those boxelder trees, and that should help reduce the population. However, my maple tree stays.

Roland’s trivia question of the week:

Have the Boston Red Sox and Los Angeles Dodgers ever met in a World Series?

The house fly, Musca domestica, is believed to have evolved in the

The house fly, Musca domestica, is believed to have evolved in the