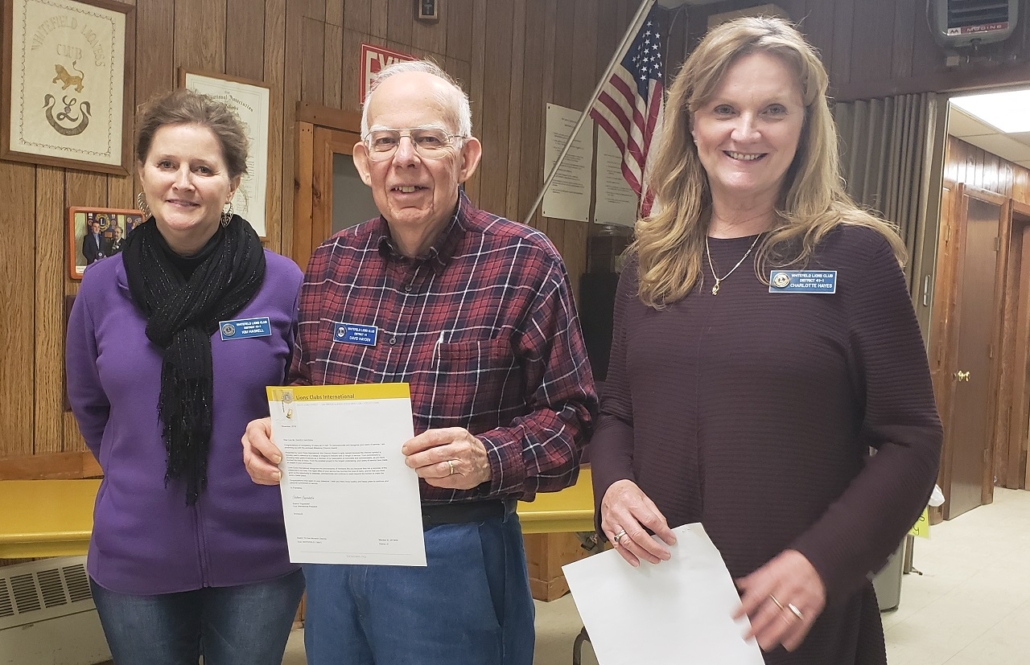

Contestants prepare for the duct tape sled competition. (Photo by Bob Bennett)

by Rick Hansen

We don’t often have the option or opportunity of opening our property to neighbors, and sometimes that feels un-neighborly. It is a consequence of the litigious world in which we live, and sometimes it can’t be avoided. We feel that there need to be times set aside for intentionally welcoming and visiting with our community… as family, as friends, and as neighbors.

Living in the northeast, we usually think of summer as the best time for community gatherings like block parties, backyard picnics, parades, and outdoor celebrations. Some of our neighbors realized that there was a need for winter community also, and that is why they approached us four years ago about being the host site for a China Community family sledding party.

We had some reservations, but decided to pray about the opportunity and then accepted the challenge. What began as a small, localized sledding event has steadily grown into an event that attracts hundreds of people looking for a day to celebrate winter fun in Maine with family and friends and neighbors. This year, February 16 was the day for the Family Fun Day… and what a day it turned out to be! Despite concerns due to lack of snow, icy conditions, unpredictable weather, etc., prayers were answered and all the pieces landed in place for a memorable outdoor event on a pleasantly mild winter day.

After months of reviewing last year’s event, brainstorming and planning for this year’s event, and reaching out to sponsors new and old, it was time for the 2019 Family Fun Day to begin. Volunteers arrived throughout the morning, ready to serve their neighbors in the kitchen, dining hall, and sledding areas. That included some Jobs for Maine Graduates and other students from China Middle School as well as several adults. Final adjustments were made to the sledding hill and the delicious food that was very generously provided by Big G’s, in Winslow, was warmed.

Banners, provided by Central Church of China, were hung around to direct families to the festivities while Fletcher’s Lawn and Yard Care spread sand on the icy areas. Bar Harbor Bank and Trust set up a table from which they offered Gatorade, cocoa, and sunglasses near where Bob’s Glass and More set up a S’more station so that people could warm by the fire and make their own S’mores with ingredients donated by Gene at Lakeview Lumber. Delta Ambulance and China Village Fire and Rescue were both represented, making sure that any sledding injuries were quickly and skillfully handled.

The China Four Seasons Club brought their new trail groomer and sleigh to offer rides through the field by the lake. The cardboard (and duct tape) sled race capped off the day as imaginatively designed, homemade sleds sped down the hill, racing for gift card prizes purchased with donations by LaVerdiere’s General Store, Branch Mills Heating Solutions, Lakeview Lumber and others.

Other ingredients for the day were donated by local churches and individuals, and everyone was so blessed by them! Because of such generous donations of time and resources, there was absolutely no charge to enter, participate, eat, and enjoy the fellowship with neighbors. Family is foundational in this community, and the local definitions of neighbor and family are often one and the same.

We appreciate the generosity of our sponsors, those who brought gifts of food which were donated to the China Food Pantry to help keep our neighbors fed this winter, and those who donated their time to come serve their community and neighbors.

Planning for a 2020 Family Fun Day has already begun and we expect to make a few improvements for next year. We hope to see you then!

The Hansens are Camp Directors at China Lake Camp.

In Burlington, Vermont, Kaitlyn Sutter, of Palermo, along with 40 teams and over 700 participants, has helped the University of Vermont’s annual student-led fundraising event RALLYTHON raise a record-breaking $117,520.29 for the UVM Children’s Hospital.

In Burlington, Vermont, Kaitlyn Sutter, of Palermo, along with 40 teams and over 700 participants, has helped the University of Vermont’s annual student-led fundraising event RALLYTHON raise a record-breaking $117,520.29 for the UVM Children’s Hospital.

Tim Theriault, Chief, China Village FD

Tim Theriault, Chief, China Village FD A spectacular evening of ballet, contemporary dance, tap, and jazz, “Moving Stories” showcased exciting new dance works November 8-10, 2018 at Muhlenberg College’s Trexler Pavilion for Theatre & Dance, in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

A spectacular evening of ballet, contemporary dance, tap, and jazz, “Moving Stories” showcased exciting new dance works November 8-10, 2018 at Muhlenberg College’s Trexler Pavilion for Theatre & Dance, in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

Mikayla Reynolds, a senior at Winslow High School, is one of six Maine girls who will receive an award at Hardy Girls Healthy Women’s 12th annual Girls Rock! Awards on March 22. The girls were nominated by their communities to be honored for their outstanding achievements in one of the following categories: STEM, athletics, entrepreneurship, health advocacy, community organizing, and defying the odds for success. Mikayla was chosen for her outstanding achievements in community organizing. Here is what was written about Mikayla for her nomination:

Mikayla Reynolds, a senior at Winslow High School, is one of six Maine girls who will receive an award at Hardy Girls Healthy Women’s 12th annual Girls Rock! Awards on March 22. The girls were nominated by their communities to be honored for their outstanding achievements in one of the following categories: STEM, athletics, entrepreneurship, health advocacy, community organizing, and defying the odds for success. Mikayla was chosen for her outstanding achievements in community organizing. Here is what was written about Mikayla for her nomination: