Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Agriculture – Part 5

by Mary Grow

Race horses and work horses

Some of the central Kennebec Valley agricultural pioneers chose to breed racehorses, specifically trotters, instead of, or in addition to, the cattle discussed last week. For example, Kingsbury mentioned in the chapter on Waterville in his Kennebec County history that George Eaton Shores, of Waterville, who bred Hereford cattle, “also handled some horses, selling in 1879 the race horse Somerset Knox for $2,700.”

The April 2016 lead article in a publication called Fishermen’s Voice: News and Comment for and by the Fishermen of Maine, written by Tom Seymour and found on line, offers historical information on Maine horse racing.

Seymour gave three reasons for the interest in breeding and racing horses in the latter half of the 19th century.

First, he said, by then “technological innovation made farming more efficient,” giving farm families time for recreation. Second, since many farms had horses, “it was only natural to employ these animals in something other than work-related activities.”

The third factor Seymour cited was “the new and hopeful attitude of Americans coming out of the dark days of our Civil War. Returning soldiers and their families needed something to belong to, to feel good about.”

Simultaneously, he wrote, farmers’ organizations began putting on agricultural fairs in late summer and early fall. Therefore, “Maine’s fairgrounds included not only buildings where people exhibited new, perfectly-shaped and sometimes giant vegetables and flowers, but also raceways.”

An on-line source says horses in the first trotting races were “under saddle,” but soon they were “in harness,” pulling first a wagon, then a two-wheeled sulky and as the sport developed, a bike sulky, the light-weight, two-wheeled single-seat cart still used today.

Seymour wrote that there were more than 100 Maine trotting parks during the post-Civil War decades, enough so that “horse owners were able to go from one trotting park event to another, with little time left in between.” With prizes for winning races and publicity that led to stud fees, owning a good trotting horse became financially rewarding, as well as a source of pride and prestige for breeder and owner.

Your writer was unable to learn more about the horse named Somerset Knox mentioned above, except that he was one of many descendants of General Knox, described in an 1895 issue of the Eastern Argus (Portland) as Maine’s most famous horse. General Knox was owned for 14 years by Col. Thomas Stackpole Lang, of Vassalboro, another area farmer who bred both cattle and horses.

A register of American Morgan horses found on line says that General Knox, also known as Slasher, was born in June 1855, in Bridport, Vermont (a town at the south end of Lake Champlain), and died July 29, 1887, in Trenton, New Jersey. He is described as “black with star and snip, nose, flanks and stifles brownish, 15 ½ hands and weighed 1050 pounds.”

(The world-wide web says a star is a white mark on a horse’s forehead between the eyes; a snip is a white patch on a horse’s nose; a stifle is a hip joint; and a hand equals four inches.)

Lang bought General Knox in January 1859, for $1,000. He was used primarily for breeding, as Lang showed in an August 1870 Maine Farmer article he wrote (quoted in the Morgan register).

Lang said of General Knox: “His temper is always good, always cheerful and full of spirits and ambition, and never nervous at the most exciting sights and noises. Strike him in anger or abruptly, and it must be a strong man to hold him even when tired with trotting, yet entirely under control of the voice; attaches himself readily to those who pet him, and when away from home on the boat or on the cars, lies down to rest readily if his groom lies down with him.”

Lang described two trotting races General Knox won in the early 1860s, the first when the horse was seven years old.

The General was supposed to compete in Skowhegan against General McClellan, in response to a challenge from McLellan’s then-owner, G. M. Robinson, Esquire, of Augusta. However, Lang wrote, Robinson withdrew McClellan, because a few days earlier a horse named Hiram Drew had beaten him in Portland and Hiram Drew was running in Skowhegan.

General Knox had 22 days to relax from his stud duties and prepare for the race, “having served 136 different mares since April.” (Lang did not say what month the race was; your writer guesses September.) He “beat Hiram easily in three straight heats, without a break.”

(E. P. Mayo, in his chapter on agriculture in Edwin Whittemore’s history of Waterville, said General Knox outpaced Hiram Drew on Oct. 22, 1863, in Waterville. He wrote that supporters of both horses came from all over Maine to watch the race, “which is recalled even to this day by the oldest lovers of racing as one of the great events of their lives.”)

Lang wrote that he intended to stop racing General Knox, but was persuaded to enter him to uphold Maine’s honor in the Springfield fair (presumably, the fair in Springfield, Massachusetts, now the Big E [for Exposition], dubbed the only multi-state fair in the world and held this year Sept. 15 and 16).

That year (1863 or 1864) General Knox had served 112 mares since April and had 15 waiting. Lang and the General left home on a Thursday morning and reached Springfield Sunday morning. General Knox raced on Thursday and won easily.

They came back as far as Boston Thursday night, “making,” Lang wrote, “in all 21 days from the time he was drawn from service until he had traveled upon cars and boat three days without rest, won his race and was bound home.”

After the race, Lang wrote, four other New England horsemen offered to buy General Knox, bidding up to $30,000. Lang declined. He wrote that Knox had raced only once since, in 1866, and in 1870 was anticipating the most mares he had ever served in one year.

In 1872, the on-line Morgan register says, Lang sold General Knox, for $10,000. The register includes a list of some of his descendants, with remarks about two or three.

Mayo wrote in the Waterville history that Waterville’s trotting park was initiated by the North Kennebec Agricultural Society, legislatively incorporated July 31, 1847 (and mentioned last week in connection with early officers Joseph and Sumner Percival).

In January 1854 the society appointed a committee to find land for a racetrack. A site was chosen in southern Waterville and a half-mile track was built, perhaps the same year.

On Aug. 22, 1863, Mayo found, the track “was leased to the Waterville Horse Association for their annual exhibition.” T. S. Lang was one of the signatories to the lease.

Mayo also found in the society’s records an Oct. 4, 1859, vote of thanks to Lang for donating his horses’ prize money to the society. He quoted: “He ever strove to win all the prizes that he could in order that the society might be the more benefited thereby.”

The North Kennebec Agricultural Society gave annual exhibitions into the 1880s, until increasing competition from nearby towns’ fairs caused members to give up. They leased the track for a while and finally sold it “for the enlargement of our present beautiful [Pine Grove] cemetery.”

* * * * * *

Alice Hammond, whose history of Sidney was published in 1992, did not mention any Sidney horse-breeders, but she gave more detail than many other historians about horses as work animals.

In her chapter on agriculture, she summarized sequential methods of harvesting hay: men mowing with scythes gave way to “horse-drawn mowing and raking machines,” which in turn were displaced by “mechanical reapers and balers.”

On-line sites say the first horse-drawn mowers date from the 1840s or 1850s. The machines became popular after the Civil War, and, one source says, are still used in this century in special areas like nature preserves and organic farms.

But it was in her chapter on transportation that Hammond expanded on the important role horses played on early Sidney. The Kennebec River was important, and she mentioned oxen, for example used to build the first roads.

Most of these roads succeeded bridle paths, which followed earlier Native American trails. In the late 1700s, the “bridle paths were widened to allow pack horses and even carts and sleds in season.”

Through the 19th century and into the 20th, Sidney residents rode horseback or in horse-drawn carts or wagons. Road maintenance depended partly on horse labor; Hammond wrote that between 1860 and 1870, horses pulled the “road scrapers with metal blades” that “were used to shape and smooth the roads.”

“Later,” she continued, “mechanical road machines pulled by horses were used,” until trucks replaced the horses.

Hammond quoted an article written by an earlier Sidney resident, Russell M. Bailey, on winter travel and road maintenance early in the 20th century, with horses still a major power source. She gave no dates for events he described; one of the genealogies in her history says he was born in 1901.

Bailey wrote that there were three kinds of personal winter vehicles. The fastest and fanciest was the single-seat sleigh, “with a sweeping high curved dashboard and luxuriously upholstered seat.” One horse, “a light driving horse if available,” pulled the sleigh.

The pung was “a lower slung, long runnered, single horse utility winter vehicle, suitable for hauling light loads or the family.” For heavy loads, a farmer would use the double sled drawn by a pair of work horses.

To keep roads passable, Sidney and other Maine towns used snow rollers, large wooden and metal contraptions that packed down the snow. On-line sources say horse-drawn rollers were used from the late 1880s into the 1930s.

Hammond wrote that in 1895, Sidney “raised money to build snow rollers.” Bailey described a Sidney roller as pulled by eight horses, in two sets of two teams.

Hammond included a story of a winter storm Bailey remembered that covered roads with more than a foot of new snow under a thick icy crust. When the horses’ hooves broke though the crust, the sharp edges cut their legs.

After protective padding failed, Bailey wrote, “additional men were hired to proceed the lead team to break the crust with their feet and shovels.”

Main sources

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous.

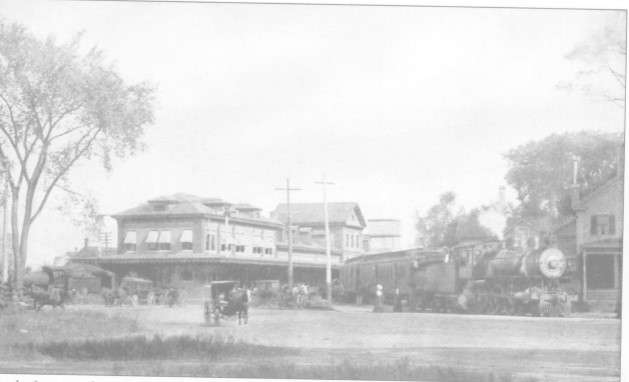

CORRECTION: In last week’s article, the location of Waterville Railroad Station was incorrect. It should have said, the Waterville railroad station was located on what is now an empty lot, on the west side of College Ave., to make room for Colby St. circle where it intersects with Chaplin St., near Burger King. The railroad tracks that cross Chaplin St. are an indication of where the train terminal was located. The locomotive pictured in this 1920s photo, is located where the train tracks cross Chaplin St.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!