Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Native Americans – Part 1

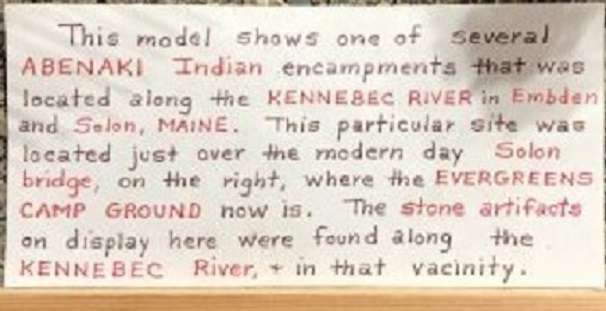

This model and an inscription of a typical Abenaki encampment can be viewed at Nowetah’s Indian Museum, in New Portland.

by Mary Grow

Logically, your writer should have started this series on the history of the central Kennebec Valley with the first human inhabitants, the groups once called Indians and now more commonly called Native Americans.

Your writer is a coward. She did not want to take on a topic about which there is no contemporary written evidence and limited later evidence.

However, in collecting information for the series it has become clear that reliable, unbiased and uncontradicted evidence is in short supply on most topics. Therefore, it is time to write about prehistoric – or better, pre-European-historic – Native American life in the central Kennebec Valley. Readers are hereby warned that everything written, no matter how authoritative the source sounds, might be wrong.

There are two areas to research: reports on archaeological excavations and interpretations of the findings; and written records by 16th and 17th European explorers, missionaries, traders and the like, as edited by later historians.

The archaeological record is incomplete in two ways: a vast amount of evidence of the way people live does not survive for hundreds of years; and modern archaeologists have found only small samples of what did survive. Nor have they necessarily correctly interpreted their findings.

Written records, too, have an interpretation problem. Europeans arriving on the coast and moving inland viewed a very different culture through their own cultural lens. Some wanted to denigrate the indigenous people, others to glorify them, and even those who intended to be purely descriptive could not necessarily understand what they were seeing.

This article will present an arbitrarily-chosen triple overview: linguistic issues; a brief and incomplete description of Native American life in Maine; and comments on relations between Maine’s Native Americans and European settlers. A subsequent article (or articles) will discuss what is known and surmised about pre-contact Native Americans in the central Kennebec Valley.

The linguistic issue involves tribal names and their spellings. The Native Americans lacked a written language, so Europeans transcribed the sounds they heard in a variety of ways.

Further, they applied them differently. Ernest Marriner wrote in Kennebec Yesterdays that the Native Americans did not give names to large areas of land or water, but only to specific smaller places, like a section of a river. The word “Kennebec” is indigenous; “Kennebec River” is European.

The Native Americans who were living in the Kennebec River Valley when the Europeans began arriving were a tribe whose name is commonly spelled Kennebec. Other spellings, listed in various sources, have included Caniba, Kenabe, Kennebeck, Kinibeki, Kinipekw, Quinebequi, Quinibequi and Quinibequy.

The last three are allegedly French explorer Samuel de Champlain’s spellings. Henry Kingsbury, in his Kennebec County history, wrote that Quinibequi was the French spelling of a Native American word, Kinai-bik, that meant “monster.” It referred to an underwater monster whose movements supposedly caused the dangerously turbulent water Native Americans encountered in the winding passage between Bath and Sheepscot Bay, where river water met tidewater.

Kingsbury and William Williamson, in his Maine history, each mentioned a Native American chief named Kennebis, who in 1649 “conveyed” to Europeans an area as far up the Kennebec River as Ticonic Falls.

Ticonic (or Teconnet) is another Native American name that is still in common use. Kingsbury said “Ticonic” was the name for the place where the Sebasticook River flows into the Kennebec, and also for the rapids a short distance upstream.

Another lasting name is Cushnoc (Cusenage in the 1650s, according to Kingsbury, or Cushenock in the 1690s, according to one of Williamson’s sources). Several historians agree it comes from a Native American word that means the place where the tide stops flowing upstream, as on the Kennebec at Augusta.

The Kennebecs were among several subtribes of the Eastern Abenaki (or Abenaque, Abenaqui, Abnaki, Abnakki, Abinaki, Alnôbak), also called the People of the Dawn. The Abenaki were one of several groups of Algonquian-speaking Native Americans who lived in what are now the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada.

Before Europeans arrived, the Kennebecs and related tribes lived off the land. Houses, tools and utensils, clothing and weapons were made of materials like wood; stone; grasses that could be woven; and animal hides, antlers and other useful parts.

Food came from hunting and trapping, fishing, collecting berries, nuts and other wild edibles and to a lesser extent growing crops. Multiple sources list the principal crops as corn, beans, squash and smoking tobacco. Some add potatoes, pumpkins and other vegetables.

Hunting weapons included lances and spears made of wood with sharpened stone points. Chert, a fine-grained, hard rock related to flint, was the preferred material for points.

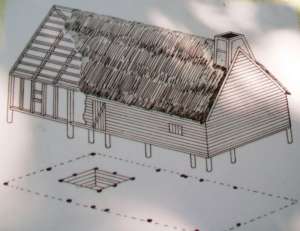

Historians describe houses as oval or round, made of different materials depending partly on whether use was seasonal or year-round. One common type was the teepee or wigwam, constructed of branches slanting upward and tied at the top. Animal hides or mats woven from plant fibers covered the outside to keep out wind and water. Year-round houses might have floors of gravel sunk below ground level.

Warmth came from a fire pit, central or near the doorway. Smoke went out through a hole in the roof where the branches met. Mats or animal skins lined the lower part of the inside and covered the benches along the walls for warmth and comfort.

Native Americans traveled on foot on land, aided by snowshoes in the winter; there is no record of use of horses or similar animals or wheeled vehicles. Water travel was in dugouts and later in birchbark canoes.

Many people traveled; for example, seasonal camps would be set up on rivers and streams, including in the Kennebec Valley, in spring when river herring and salmon were migrating and on the coast in the summer.

The first Europeans began ascending the Kennebec in the 1620s. After about half a century of reasonably peaceful relationships, war broke out between the Native Americans and the English settlers. The wars that make up the Second Hundred Years War between Britain and France were fought mainly in Europe; they overflowed into the colonies, where they merged with local issues.

Williamson and Robert P. Tristram Coffin (in his Kennebec Cradle of Americans) each counted six separate wars, starting in the 1670s and ending in the 1760s. The British conquest of Québec in 1759, made permanent in the 1763 Treaty of Paris, eliminated France’s role in the northeastern United States.

Cranmer, in his Cushnoc, and the unnamed authors of The Wabanakis of Maine and the Maritimes added local reasons for hostility, based on major cultural differences. The latter writers said that the Native Americans lived in a world of abundance – except, sometimes, in late winter when stored food supplies ran low, they had all they needed and shared generously.

Williamson agreed, describing a community in which accumulating property was neither praised nor practiced, no one stole and trade was fair. Instead, the Native Americans valued and helped other people, whether neighbors or strangers.

(These historians, and others, did not glorify the Native Americans, however. Their vindictiveness against those who offended them and their cruelties in war were described in terms sadly reminiscent of the present day.)

When the first trading posts opened, the English needed the indigenous people. In addition to acquiring furs to sell, traders needed help getting food and shelter in this new environment; and the Native Americans extended their sharing to the invaders.

From the traders, the Native Americans accepted materials that made their lives easier, like metal instead of stone tools. As time went on, Cranmer said, they abandoned their old skills and became increasingly dependent on imports, and therefore on the importers. The result of the reversed relationship was complicated by the introduction of firearms and liquor, and led to the Native Americans beginning to resent the in-comers.

Resentment increased, Cranmer and other historians wrote, as the English imposed their ideas, especially the totally foreign idea of individual land ownership. British settlers cut down trees, built houses and fenced gardens and cattle pens, eliminating habitat for game animals and making traditional foods less available.

Their holdings cut off access to rivers, and they punished Native Americans who trespassed on land they claimed. Further, they captured Native Americans to sell as slaves, and killing a Native American was not a crime. One historian said scalping was practiced in Maine by Europeans and Native Americans alike.

A major effect of the arrival of Europeans was the spread of European diseases – measles, chicken pox, smallpox, influenza and many others – against which Native Americans had no immunity. In the 17th century, thousands died. The writers of The Wabanakis explained that with elimination of entire families and even entire villages, deaths of leaders and discrediting of shamans (curers or “medicine men”), native governmental and social structures were disrupted.

Williamson wrote (rather arrogantly) that “In the first settlement of this country, the judicious management of the natives was an art of great importance.” The British weren’t very good at it, he said.

But, Williamson wrote, the French, “by a condescension and familiarity peculiar to their character,” did better in making friends and allies. Other historians agree that the French who came south from Québec were generally respectful of Native Americans. Coffin wrote that unlike most of the British, the French intermarried with Native Americans.

Another reason for French popularity was their willingness to sell firearms to Native Americans, who found them useful for hunting. British traders were strictly forbidden to arm Native Americans, lest the arms be turned against them (though the prohibition was not always obeyed).

Additionally, French Catholic priests were welcomed, notably the succession of able men who served at Norridgewock, like the Jesuits Father Gabriel Dreuillettes (1610-1681) and Father Sebastien (or Sebastian) Rasle (or Rale, Ralle, Rasles) (1652-1724). These men came as friends, not masters, and several historians say Catholicism fitted readily into the indigenous way of life.

Consequently, when wars spread from Europe to the budding colonies along the Maine coast and tributary rivers, most Native Americans sided with the French, with disastrous results for early British settlers on the Kennebec. The removal of French influence, and the effective destruction of Native Americans in the Kennebec Valley, made the region safe for British expansion.

Cushnoc Trading Post replica planned

An article by Chris Bouchard in the May 29 issue of the Kennebec Journal announced that leaders of Old Fort Western have started raising money to build a replica of the Cushnoc Trading Post.

Bouchard quoted museum director and curator Linda Novak as saying the replica will be built behind the fort. The original site was nearby on what is now the lawn of the First Church of Christ, Scientist, at 6 Williams Street.

The reconstructed building is to be “a post and beam structure with earthfast construction.” Novak explained that “earthfast” means no foundation; “the vertical roof-bearing posts will come in direct contact with the ground.” The floor will be either planks or dirt.

Because the trading post will be open to the public, Novak said, it must include anachronistic elements required by contemporary building codes, like fire alarms and a sprinkler system.

The fund-raising goal is $250,000, and the preferred deadline is 2026, to allow Novak and supporters to buy special Canadian lumber that needs to be dried for two years and to open the new trading post in 2028, the year Novak calls the 400th anniversary of the original.

In December 2021, former Augusta Mayor David Rollins proclaimed 2022 The Year of the Fort. His proclamation, a history of the fort and much more information can be found on line by searching for Old Fort Western.

Main sources

American Friends Service Committee, The Wabanakis of Maine and the Maritimes (1989).

Coffin, Robert P. Tristram, Kennebec Cradle of Americans (1937).

Cranmer, Leon E., Cushnoc: The History and Archaeology of Plymouth Colony Traders on the Kennebec (1990).

Hatch, Louis Clinton, ed., Maine: A History (1919; facsimile, 1974).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Marriner, Ernest, Kennebec Yesterdays (1954).

Williamson, William D., The History of the State of Maine from its First Discovery, A.D. 1602, to the Separation, A.D. 1820, Inclusive Vol. I and Vol. II (1832).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Read part 2 of this series here.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!