Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Native Americans – Part 4

by Mary Grow

East side of and away from the Kennebec

Last week’s article talked about Native American sites along the Kennebec River between Fairfield and Sidney on the west bank, but the east bank between Ticonic (Winslow) and Cushnoc (Augusta) was skipped for lack of space. This week’s article will remedy the omission by talking about Vassalboro and about sites inland on the east side of the river (as was done for the west side last week).

Vassalboro either was popular with the Kennebec tribe or has been more thoroughly explored than other areas (or both), because various histories mention several areas connected with Native Americans, including at least one Native American burial ground on the Kennebec.

Alma Pierce Robbins, in her Vassalboro history, quoted a historian of the Catholic Church in Maine who claimed Mount Tom was an “Indian Cemetery.” Mount Tom is now in the Annie Sturgis Sanctuary a little north of Riverside, on the section of old Route 201 between the present highway and the river named Cushnoc Road.

Charles E. Nash, in the chapter on Native Americans in Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history, reported a large burial ground north of the mouth of Seven Mile Stream (or Brook), which runs from the southwest corner of Webber Pond to join the Kennebec at Riverside.

Kingsbury himself, in his chapter on Vassalboro, suggested that Robbins’ source and Nash were talking about the same site. Kingsbury wrote that the burial ground was the south side of Mount Tom, “sloping to the brook, on the Sturgis farm.” Artifacts and bones were still “plentiful” there in 1892, he said.

Nash wrote that the Native American name for Seven Mile Brook was Magorgoomagoosuck. James North, in his history of Augusta, spelled it Magorgomagarick.

The pestle was used against the mortar for crushing and grinding and were commonly used for meal preparations such as reducing grain and corn into wheat and meal. Mortar and pestles would have also been used in the preparing of medicine as well as the manufacturing of paint.

An undated on-line copy of a University of Michigan document titled Antiquities of the New England Indians includes descriptions and photographs of a variety of artifacts, including knives, axes and mortars and pestles. The writer explained that mortars and pestles, either wooden or stone, were essential for crushing dried corn kernels.

One pestle that the writer particularly admired came from Vassalboro, and when the description was written it was owned by Kennebec Historical Society. It is now in the Maine State Museum, according to KHS archivist Emily Schroeder.

The pestle is described as 28.5 inches long, made of green slate, topped with a small human head. The illustration shows an almost round head, with oval eyes, a nose indicated by two straight lines with a connecting line at the bottom and a pursed mouth. The writer said the lower half of the pestle was found near Seven Mile Brook; the upper half was found a few miles away four years later, and “The two pieces fitted perfectly together.”

The pestle was broken intentionally, the writer asserted. He wondered whether the destruction of what could be seen as an idol was related to the nearby seventeenth-century Catholic mission.

There are also references to a Native American site farther north along the river, on the section of old Route 201 called Dunham Road.

Robbins wrote that many artifacts had been found on the shores of Webber Pond – so many, she said, that cottages built around 1900 used them as trim around fireplaces.

The major Native American site in Vassalboro located and partly investigated to date was at the outlet of China Lake in East Vassalboro, partly on property on the east side of the foot of the lake and the east bank of Outlet Stream owned for generations by the Cates family. The Vassalboro Historical Society museum in the former East Vassalboro schoolhouse has a room dedicated to information about and artifacts from the site.

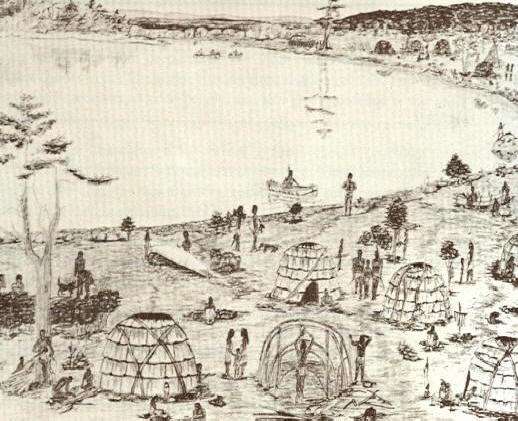

According to the exhibit, the area was occupied at least sporadically from 10,000 years ago until Europeans displaced the Native Americans. Different types of tools, weapons and houses are displayed or illustrated and explained. Alewives were harvested at the China Lake outlet 5,000 years ago.

Correspondence on exhibit shows that the Maine Historic Preservation Commission listed the Cates farm site as a protected archaeological site on the Maine Register of Historic Places in the fall of 1989, as requested by George Cates.

The part of China Lake that is in the Town of China was also frequented by Native Americans. The town’s comprehensive plan says the Maine Historic Preservation Commission has found prehistoric sites on two islands in the lake, Indian Island in the east basin and Bradley Island in the west basin (plus one at the north end of Three Mile Pond, and an accompanying map shows a fourth site on Dutton Road). Commission staff think it “highly likely” that there are other sites in town, especially along waterways.

According to the China bicentennial history, the lake was part of one of the Native Americans’ routes inland from the coast in the fall. After final seafood feasts, people would paddle up the Sheepscot to a place about two and a half miles south of China Lake, portage to the south end of the lake and paddle northwest to the outlet in Vassalboro. From there Outlet Stream carried them to the Sebasticook and then to the Kennebec at Ticonic.

The Kennebecs left behind on the west shore of the southern part of the lake’s east basin a heart shape carved into a boulder. World-famous Quaker Rufus Jones, of China, told a story about this carving several times, including as a chapter in Maine Indians in History and Legends.

Jones began by warning readers that his version of The Romance of the Indian Heart is part history and part imagination. He refused to say which was which.

The legend features a Kennebec brave named Keriberba, son of Chief Bomazeen (or Bomaseen, mentioned in the June 9 article in this series), from Norridgewock, and his wife Nemaha, from Pemaquid, whom he met at one of the annual seafood feasts at Damariscotta.

Coming home from the coast, Keriberba, Nemaha and their companions stopped to roast and eat the last clams on the west shore of China Lake’s east basin by “a large sentinel granite rock” from the glacial age. They continued to Norridgewock, where Father Sebastian Rale married them beneath a picture of the Sacred Heart that hung above the altar.

Nemaha immediately organized a group named “The Sisters of the Sacred Heart,” Jones wrote. The women took lessons from Father Rale and hosted an annual feast.

When the British soldiers made their final and successful attack on Norridgewock in August 1724, Keriberba and a few other young men “escaped across the river.” Nemaha grabbed the picture of the Sacred Heart from the church and with others of her sisterhood ran to a secret hiding place in the woods.

The next morning the two groups reunited. After burying Bomazeen, Father Rale and others, they gathered up what the British had left of their belongings and went back to settle at the feasting spot on China Lake.

Jones described the 300-year-old pines that sheltered their wigwams, and the shrine they built for the Sacred Heart picture that became “the center of their religion.” The importance of the picture was reinforced when, one evening, Keriberba called across the lake, “Le sacré Coeur,” (“the sacred heart” in Father Rale’s native French). His words echoed back to him across the water.

Jones wrote that he too had experienced the echo, from the place on the shore that repeats whole sentences. But to the Kennebecs, it seemed to be the voice of the Great Spirit. From then on, Keriberba called every evening and they were comforted by the reply.

Jones described years of living in peace, traveling to Norridgewock to grow corn (because they could not clear enough land by the lake), hunting deer, moose and an occasional bear, importing clams that fed muskrats (both edible), netting and smoking alewives. As children were born and grew up, the group became larger.

One night, a storm destroyed the Sacred Heart shrine and blew the picture into the lake, where it turned to pulp. The next day, Keriberba began carving a recreation of the sacred heart into the granite rock.

When his picture was finished, the group feasted and danced until late at night. Before they went to bed, Keriberba stood beside his carving and shouted, “Le sacré coeur” – and the words came back just as they should.

There is a little more to Jones’ story; it will be continued next week.

* * * * * *

Your writer has found only bits and pieces of information about Native Americans in the areas now included in the towns of Albion, Clinton and Palermo, and nothing from Windsor.

The 2004 report on the archaeological survey around Unity Wetlands and along the Sheepscot River, reprinted on line and mentioned last week, cited a person named Willoughby who, in a 1986 publication, described one pre-European relic from Albion. The reference is to “an isolated Indian artifact recovered by a farmer in the town of Albion – a ‘mask-like sculpture’ of sandstone with pecked and incised eyes, mouth, and other facial lines. It is unclear if the portable rock sculpture was found within the Unity Wetlands study area or simply nearby.”

A photo of what is almost certainly the same sculpture, described as “found while digging potatoes in Albion, Maine” appears in the on-line Antiquities of the New England Indians. The writer described the head as sandstone, about 10 inches long by two inches thick at the thickest point.

The writer continued, “Its natural smooth surface was used for the face, and the rougher fractured surface of the back was smoothed by pecking.” The face tapers to a chin; ears round out on either side; two small round dark eyes each has a circular outline; a smaller dark circle represents the nose; and parallel horizontal lines make a slightly off-center mouth.

The writer described traces of red pigment on the front and yellow pigment on the back. He surmised the effigy came from a grave.

Clinton’s 2006 comprehensive plan says the Maine Historic Preservation Commission had found four prehistoric sites within the town boundaries, one on the Kennebec River, one on the Sebasticook River and two on Carrabassett Stream. Commission staff suggested waterside archaeological surveys. The 2021 plan gives no new information.

Palermo historian Millard Howard doubted there were permanent Native settlements within the boundaries of present-day Palermo, either before or after 1763, because, he wrote, most settlements were on rivers like the Kennebec or the lower Sheepscot.

Kerry Hardy’s map of Native American trails converging on Cushnoc shows one from the coast near Rockland that crosses the east branch of the Sheepscot River a little north of Sheepscot Pond, about where Route 3 now runs east-west a bit south of the middle of town.

Linwood Lowden began his history of the Town of Windsor with the first European settlers. Because the Sheepscot River running out of Long Pond is in southeastern Windsor, including the junction of Travel Brook, it seems likely that parts of the town would have been at least a Native American travel route, if not home to settlements.

Main sources

Grow, Mary M. China, Maine Bicentennial History including 1984 revisions (1984).

Hardy, Kerry, Notes on a Lost Flute: A Field Guide to the Wabanaki (2009).

Howard, Millard, An Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine (second edition, December 2015).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Maine Writers Research Club, Maine Indians in History and Legends (1952).

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!