Jack’s: Where everybody knows your name

by Eric W. Austin

Growing up near China Village in the latter half of the last century, there was one place everyone visited at least once a week. Officially named China General Store, Incorporated, most of us knew it simply as “Jack’s.” It was the center of life in China Village for more than 50 years.This is the story of Jack’s General Store, and the man who ran it.

Jack Sylvester was born to a family from Eustis, Maine, on Friday, October 13, 1938. From this inauspicious beginning, young Jack would grow up to have a profound influence on another community far to the south of the place of his birth.

Jack’s father and grandfather operated a livestock business in Eustis, providing horses to businesses all over the state of Maine, especially those involved in the logging and farming industries, which at the time still relied on horsepower to get the job done.

By the early 1940s, however, the horse business in Eustis was flagging, and the Sylvester family moved south to Albion when Jack was only six. Jack’s maternal grandparents had a residence in Albion, and the Sylvesters hoped the busier metro-area of Waterville and Augusta would keep the horse business going for a few more years.

In Albion, Jack Sylvester attended Besse High School, which was located in the brick building that now houses the Albion Town Office. Jack vividly remembers the day in 1957 when, during his senior year, the school burned down.

“I was on the fire department at that time, and I can tell you exactly where I was,” he says. “I was cleaning out the horses of manure.” The Sylvesters’ livestock farm was located not far from the school. He continues: “I heard the fire alarm go off, and I turned ‘round to look and that old black smoke was just roaring.”

Teenage Jack dropped his shovel and rushed to the scene of the fire. He wasn’t happy. “You’d think I’d feel good that the school burned down — you don’t have to go to school no more,” he says, flashing a characteristic Jack-grin. “But I felt terrible ‘cause the school was burning down. I set there with a hose, puttin’ water on it, and cryin’ like crazy!”

The cause of the fire was never discovered. The superintendent at the time, who will go unnamed, was the only one in the building, in his office on the upper floor. The superintendent wanted Albion to join the local School Administrative District (SAD), and there was talk around town that he had started the fire in an effort to force a decision on the matter. Nothing was ever proven, however, but after the fire, Jack tells me, “He moved out of town right off quick.”

After high school, Jack worked as a grease monkey for Yeaton’s Garage for a couple of years, and then got hired by Lee Brothers’ Construction, work that sent him all over the state of Maine. That’s where he met Roy Dow.

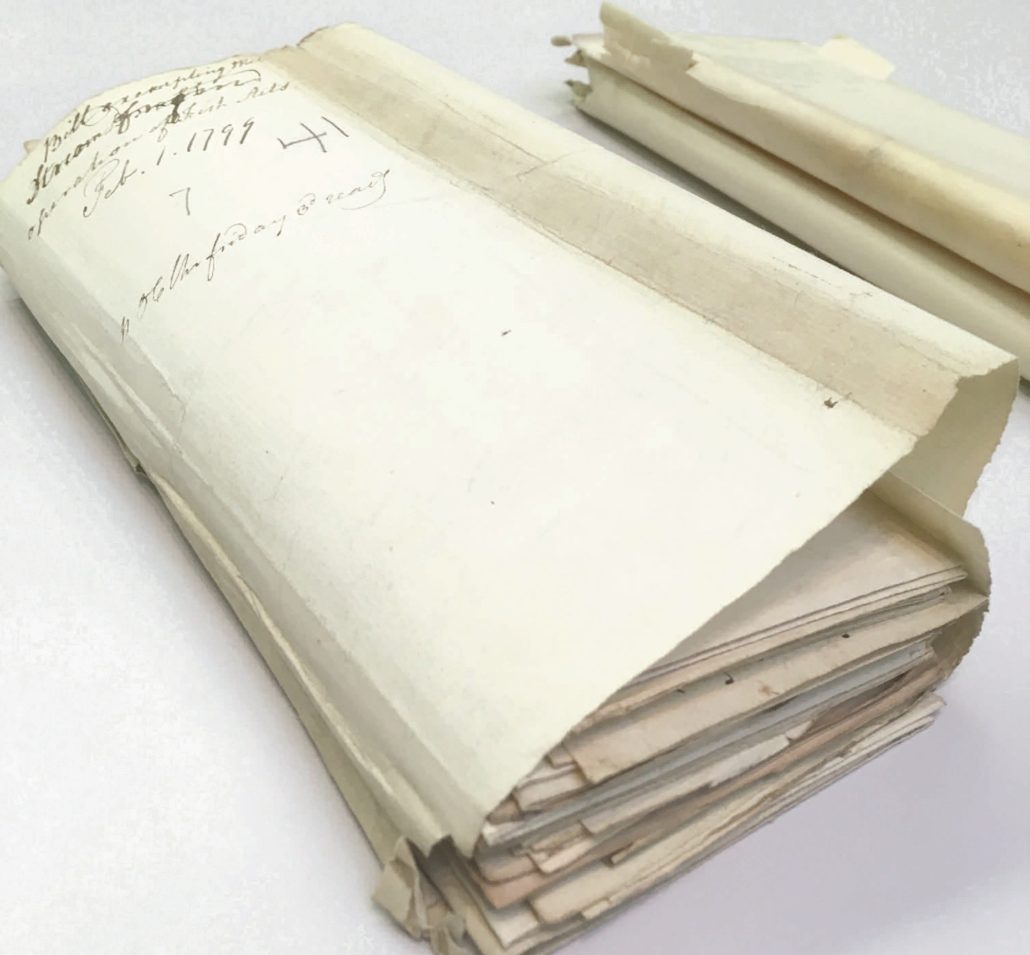

At this point, we need to pause for a bit of backstory. The tale of how Jack Sylvester came to own China General Store is the story of another fire, this time in China.

Main Street in China Village used to be quite a bit more commercial than it is now. The Masonic Lodge was on the north side of Main Street, opposite where it is now; and next to that, heading east, was the post office; a small house that is no longer there; then a bean factory (”Most every small town around had a bean factory,” says Alene Smiley, Jack’s older sister); a printing shop; a mechanics garage operated by Roy Coombs, who got his start fixing wagon wheels, and then transitioned to transmissions; and finally the old China General store, owned by the Bailey family, but later sold to the Fenlasons. The Village’s one-room schoolhouse was also located here, directly across the street from where the China library is currently.

Then on Sunday, August 20, 1961, the old China General Store caught fire and burned down. The blaze also claimed the garage and the bean factory next door, both owned by Roy Coombs. Flames from the fire leapt more than 100 feet into the air and could be seen up to 10 miles away. In a single night, nearly the entire commercial district in China Village was destroyed. Coombs, who was also serving as fire chief at the time, suspected arson as “three or four fires of suspicious nature have occurred in the town within recent months,” according to an article published the next day in the Morning Sentinel.

Photo of the aftermath of the fire at the old China General Store in 1961. (submitted by Susan Natalie Dow White)

Since the current owners, the Fenlasons, weren’t interested in rebuilding, Roy Dow and his father-in-law, Tommy James, who both worked in construction, decided to take on the job of building a new one themselves. They enlisted the help of Ben Avery, of Windsor, and chose as the location for the new establishment a spot on the eastern end of Main Street. It would turn out to be a propitious choice of location when the 202 throughway was built a decade later.

“I’d always loved the store business,” says Jack. “So, one day I was down there [at the new store], visiting Roy. He was sittin’ in front of the cash register in an old recliner. He said, ‘What’re you doin’? Why don’t you come work for me? I need a meat cutter.’ I said, ‘For God’s sake, Roy, I’m a truck driver; I ain’t a meat cutter!’ He said, ‘I’ll teach you.’”

And Roy did, and much else besides. Jack learned how to cut meat, how to manage a store, and how to select the best cuts of beef for the store freezer. He also got to know the store’s customers, and there was one customer in particular he was interested in. Her name was Ann Gaunce.

Ann’s family lived just down the road from the store, and she frequently passed by on her way to the post office. “Oh, she was beautiful!” Jack says, his eyes a little glassy at the memory. “Ann was walking by one day, and I was filling a car full of gas. I hollered at her and I said, ‘How ya doin’? Why don’t you come over here,’ I says, ‘I wanna talk to ya.’ So, she came over and I talked to her for a while. I got a date for that night.”

They went to see the movie “Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay!”, a flick from 1948, at the old Haines Theater, which used to exist on Main Street, in Waterville, across from where Maine-ly Brews is now. Jack and Ann’s was a romance destined to last a lifetime.

“I don’t call her Ann anymore,” Jack tells me, a twinkle in his eye. “It’s Saint Ann now. She’s put up with me for 54 years!”

Jack worked at the general store for Roy Dow until 1974. “He came in one day,” Jack recalls, “and says, ‘Wanna buy this place?’ I said, ‘I’d like to.’”

And he did. Together with his wife, Ann, and his son Chris, who became his right-hand man in later years, they took over management of China General Store, Incorporated. Jack Sylvester was 36 years old.

I ask Jack if owning a business in a small town like China had been a struggle. “No, sir,” he says. “I had a business that was wicked good. The last year I owned that business, I did over a million dollars.”

And Jack didn’t just manage one of the most successful businesses in China, he also served as selectman from 1965-67, belonged to the Masons since the age of 21, and joined the Volunteer Fire Department, first in Albion and then in China, where he served as fire chief for a number of years in the 1970s and ‘80s.

“Jack was always really good about his employees volunteering for the fire department and the rescue,” says Ron Morrell, who pastors the China Baptist Church and has lived across the street from Jack’s store since the early 1980s. “You’d go in sometimes and Ann might be the only one in the store, because all the guys were gone on a fire call. It left him short-handed sometimes.”

Jack’s favorite time of the year was Halloween, when he dressed up in a variety of creative costumes and hosted upwards of 350 neighborhood kids at his store, who came for the free chocolate milk and the bag of chips that he gave out every year.

That wasn’t the only interaction Jack had with the kids of China Village. He would, on occasion, catch a child shoplifting from his store. Pastor Ron relates one such incident that he witnessed firsthand. “One day, I came across the street for an afternoon cup of coffee,” he tells me. “Jack had some kid in the back, talking to him. I could tell something serious was going on.”

Totally coincidentally, a few minutes later a Kennebec County sheriff’s deputy also came into the store. Without missing a beat, Jack exclaimed, “See, here he is!”

Apparently, Jack had faked a call to the sheriff in an attempt to scare the kid straight. The sudden appearance of the deputy was a complete surprise to everyone, excepting, perhaps, the poor kid being interrogated.

“The sheriff’s deputy caught on real quick as to what was going on,” Pastor Ron recalls. “They had not worked this out ahead of time. The cop was really good about it, and they scared the kid good. And more than one kid, when they were an adult, came back and thanked Jack for what he’d done to set them straight, and for not getting the authorities involved. He could put the fear of God into them though,” Pastor Ron finishes with a hearty chuckle.

In April 2002, at the age of 64, Jack Sylvester finally hung up his apron and sold the general store. The new owners kept the store open for a few more years, but eventually closed it.

“It was never the same after Jack left,” Pastor Ron remembers. “People came because of Jack.”