Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Albion

by Mary Grow

There is debate over names of the first settlers in what is now Albion, partly because records are incomplete, partly because current Albion once included parts of several other towns. For example, Nathaniel Wiggin’s and several other families’ holdings at the north end of China Lake’s east basin were in Albion before the Albion-China boundary was moved north and their land became part of China.

Ruby Crosby Wiggin, in her well-researched and well-illustrated Albion on the Narrow Gauge, lists Burrills (Belial Burrill, by 1790), Crosbys, Davises (Samuel Davis, listed in the 1790 census), Fowlers, Haywoods (Nathan Haywood, by 1793) and Lovejoys. Kingsbury’s Illustrated History of Kennebec County 1792-1892 adds Libbeys (elsewhere Libbys), Prays, Shoreys and Rev. Daniel Lovejoy.

The last, Wiggin says, is probably an error. She found records in which Daniel Lovejoy’s sons said Daniel’s father, Francis Lovejoy, brought the family to settle on Fifteen-Mile-Pond (later Lovejoy Pond) when Daniel was about 14, making Francis an early settler.

Albion resembled other area municipalities in changing its boundaries and its name repeatedly. Wiggin says when the area was incorporated in 1802 as a plantation called Freetown, it was nearly square. A 20th-century map shows parallel boundaries on the east and west. On the south, a rectangle with a slanted east end indicates the 1815 transfer of the China Village area from Albion to China. The north boundary is irregular.

Wiggin says in 1803 Freetown voters asked the Massachusetts General Court to upgrade the plantation to a town. On March 9, 1804, the town of Fairfax was incorporated. In March 1821 (by then by the Maine legislature’s action) Fairfax became Lygonia (sometimes spelled Lagonia).

In January 1823, town meeting voters chose a five-man committee to ask the legislature to change Lygonia to Richmond. The petition apparently failed, for a January 1824 meeting created a seven-man committee (Daniel Lovejoy and John Winslow served on both committees) to request a change back to Fairfax. On Feb. 25, 1824, the name Albion was approved, Kingsbury says; and Wiggin says voters accepted it at an April 5, 1824, meeting.

Ava Harriet Chadbourne’s adds the following information, without specifying cause and effect. Fairfax was an 18th-century English general (the web suggests Sir Thomas Fairfax [Jan. 17, 1612 – Nov. 12, 1671], commander in chief of Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentary army).

Lygonia was the name of a former land grant in York County, Maine (whence many Albion settlers came), to Sir Ferdinando Gorges. The web adds that Gorges named the 1,600 square mile piece in honor of his mother, Cicely Lygon Gorges.

Albion was an early Greek and then Roman name for the island that became England.

In the early 19th century, Albion settlement expanded from the area between China Lake and Lovejoy Pond, sometimes called South Albion (Wiggin points out there seem to have been three areas called South Albion, and Kingsbury mentions two, with Puddle Dock the second) as stream and road junctions provided places for mills and businesses.

Fifteen-Mile Stream and tributaries meander from southeast to northwest. Kingsbury lists numerous mills; some of the earliest were William Chalmers’ gristmill and carding mill on Fifteen-Mile Stream before 1800; Josiah Broad’s sawmill and gristmill on the same stream’s east branch before 1810; Robert Crosby’s sawmill around 1812 in what Kingsbury and Wiggin call the Crosby neighborhood, with, Wiggin says, two dams across a small stream; and Levi Maynard’s sawmill, fulling mill, carding mill and gristmill, built about 1817 near a bridge across Fifteen-Mile Stream east of Albion Corner.

Albion historian Phillip Dow adds that the stream was named because part of it was 15 miles from Fort Western, in Augusta. It originates in a bog in Palermo, he says; runs northwest through a bog in northern Albion; continues north and west and is supplemented by another stream from Fowler Bog, in Unity; and eventually joins the Sebasticook River that flows into the Kennebec River.

Kingsbury says Nathan Haywood and Joel Wellington owned the only two taverns in Albion before the stagecoach route from Augusta to Bangor started running through town in 1820. (Joel was also Albion’s first postmaster when the post office was established in March 1825.) Joel’s brother, John Wellington, opened another tavern in 1820 at Albion Corner, which Kingsbury says he ran until it burned in 1860.

There have been two Albion Corners, in addition to the three South Albions. John Wellington’s tavern was at the eastern one, where the Hussey Road runs south off the main road (this Albion Corner is labeled on the map in the 1879 Kennebec County atlas). About the same time Wellington’s tavern opened, Kingsbury says Ralph Baker opened an inn at the present Corner, where the China and Winslow roads meet.

Other businesses in the first quarter of the 19th century included at least two blacksmith shops and at least five stores in different parts of town. The latter, Kingsbury comments, were needed to provide three necessities that settlers could neither find in the water or woods nor grow in their fields: molasses, tobacco and rum.

Albion Corner seems to have been Albion’s main commercial center, but Wiggin reports a thriving area at Puddle Dock in the mid-19th century. The 1856 Albion map shows 21 buildings in the area, she says, including George Ryder’s store that housed the post office. In 1856, South Albion is south of Puddle Dock, near the China and Palermo town lines.

The 1879 atlas’s map shows at least a dozen buildings near Puddle Dock still, including a schoolhouse on the east bank of Fifteen-Mile Stream. This map shows the South Albion post office at Puddle Dock.

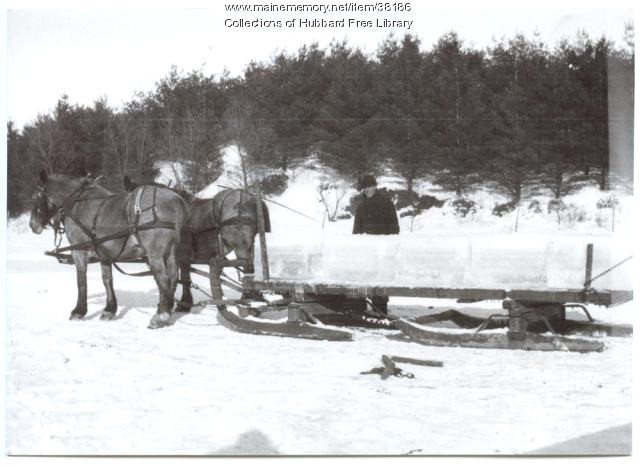

Wiggin describes the stage route between Puddle Dock and Fairfield around 1894. The Puddle Dock postmaster was M. J. Hamlin, she says. Stage-driver Martin Witham made two trips a day with mail, passengers, freight or all three, pulled by one horse in good weather and two if travel were difficult. From Puddle Dock the stage went through Albion Corner to East Benton and via three more Benton stops to Fairfield.

Some area residents still remember the dance hall at Puddle Dock. Dow says its first incarnation was in the 1940s and 1950s, when it was what he calls “a rough joint.” It closed for several decades and, Dow says, was briefly revived in the 1980s.

Daniel Lovejoy, mentioned above, had seven sons, of whom three became nationally known: Elijah Parish Lovejoy, born in 1802, martyred in Alton, Illinois, in 1837 for his anti-slavery activities; Owen Lovejoy, born in 1811, active abolitionist and member of Congress from Illinois from 1857 until his death in office in 1864; and John Ellingwood Lovejoy, born in 1817 and for three and a half years U. S. Consul to Peru, appointed by President Lincoln.

Kingsbury and Wiggin present the Crosbys as another important Albion family for many generations. The first connection was through Rev. James Crosby, one of the first settlers; Wiggin says he came around 1790. His great-grandson, George Hannibal Crosby (born in 1836) spent his working life in Massachusetts, where he was a mechanical engineer who invented and patented more than 30 improvements on gauges and valves and founded the Crosby Steam Gauge and Valve Company.

In 1886, he returned to Albion, married for the second time (to a cousin, also a Crosby), and bought a 250-acre farm on Winslow Road that had a stream and a pond. He moved the farmhouse across the road and replaced it with the Crosby Mansion, which he designed. Dow locates the Mansion (Wiggin capitalizes it) on the east side of the Lovejoy Pond outlet.

Kingsbury reproduces two pictures of the elaborate building. Wiggin includes plans of two of the five floors; the first had three piazzas, two looking west and one looking east. One piazza, she says, was built around an elm tree, because Crosby disliked removing trees. The third floor contained seven bedrooms; above it were the attic and the cupola.

The Mansion cost $75,000 or more in 1886 dollars. A feature Crosby proudly showed to visitors was a bathroom on the second floor, at the head of the south stairs. Water for flushing was stored in a third-floor tank; pulling a chain brought it down. The wooden bathtub was zinc-lined.

Dow, who has researched the history of the narrow-gauge Wiscasset, Waterville and Farmington Railroad (1895 to 1933), says Crosby supported the railroad and encouraged building the line across his land so passengers could see his house. One map of the railroad on the web shows the Crosby Tank (one of many places where train crews could take on water for the engine), and Wiggin refers in her history to Crosby’s Crossing.

After Crosby’s death the family lost the Mansion. It had several tenants and owners before it burned on Dec. 27, 1914. Wiggin says it was empty at the time and no one knows how the fire started. When she was writing 50 years later, a local family was using a piece of tile salvaged from the ruins as a hot dish mat.

Twenty-first-century Albion has a concentrated downtown around the two Albion Corners, with Lovejoy Health Center, Lovejoy Dental Center, a pharmacy, the elementary school, the town office, the library, the fire station, stores and other public and private buildings close together.

From August 1927 until January 2013, H. L. Keay & Son’s general store was one of the downtown anchors. According to a Jan. 13, 2013 Central Maine Morning Sentinel article, Harold Keay, with his wife Lena, ran the store from 1927 until his death in 1982. His son Crosby then took over; he died Nov. 26, 2011, aged 86. By 2013 the store was co-owned by Crosby Keay’s four children, Daryl, Jerry and Kevin Keay and Lisa Fortin.

Starting with a small grocery store, Harold and Lena Keay added space and inventory until by 2013 grandson Kevin Keay said the store was 8,000 square feet and there were another 8,000 square feet of warehouse. In addition to groceries, the store sold hardware, lumber and building supplies and other miscellaneous items small-town people need, and, residents commented to the Sentinel reporter, it was the place to catch up on local news.

Kevin Keay told the Sentinel business had fallen off because of the economy and competition from chain stores like Hannaford and Walmart.

The former Keay’s store has been run for a year by Andy Dow (Phillip Dow’s son). The nearby Albion Corner Store is run by Parris and Cathy Varney, of China.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed. Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892″ 1892.

Personal interview

Wiggin, Roby Crosby Albion on the Narrow Gauge, 1964.

Web sites, miscellaneous.

Most information in this section is from the comprehensive history section of

Most information in this section is from the comprehensive history section of