Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Shipping on the Kennebec River

by Mary Grow

The Kennebec River that has been an important feature of the towns and cities so far discussed in this series runs from Moosehead Lake to the Atlantic Ocean, a distance of about 170 miles. It served as the first route to the interior for Europeans, and as a known landmark in a largely unknown area.

The Kennebec Proprietors’ land extended 15 miles either side of the river, and their surveyors laid out lots from the river inland. Settlers bought and built on riverside lots before inland lots. Most travel was by water, especially if goods were to be carried.

Kingsbury’s History of Kennebec County says Captain James Howard and his sons Samuel and William were the first to use the river to export local products. (He does not specify the products; they undoubtedly included forest products; perhaps fish, since he writes later that by the 1790s the head of tide at Cushnoc falls or rapids was a source of fish for food and commerce; and perhaps crops as well.)

The older Howard had been Fort Western’s commander. After the 1763 Treaty of Paris eliminated the French from most of North America and permanently ended the need to defend the Kennebec, the fort was abandoned. Howard bought the fort and surrounding land, opened a store and built a mill, not on the main river but on a tributary about a mile north that was first named Howard’s Brook and by 1892 was Riggs’ Brook, the name it still bears.

Not all freight needed a boat. Kingsbury says when Fort Western was built in 1754, trees were cut in what is now Dresden, downriver from Augusta, shaped into building timbers, dumped into the river, hitched together and towed upstream to the building site.

The earliest story in this series explained that the area that is now Augusta started out as part of Hallowell; in February 1797 Augusta was separated and named Harrington and in June 1797 it was renamed Augusta (see The Town Line, March 26). Kingsbury says at the time of separation Harrington had 620 tons of shipping; he also lists human population, houses, cows and other statistics.

[See also: Benedict Arnold’s Québec Campaign came up the Kennebec River]

Large passenger and freight ships and boats came from Boston and elsewhere up the Kennebec as far as Augusta. Some could navigate Cushnoc rapids, and a lock for ships and for floating logs was included when the dam was built there in 1837.

The Taconic (Ticonic, Teconnet and numerous other spellings) falls or rapids just upstream from Waterville were the final limit for large boats. Upstream, and often downstream as well, settlers used a variety of wooden boats, usually flat-bottomed.

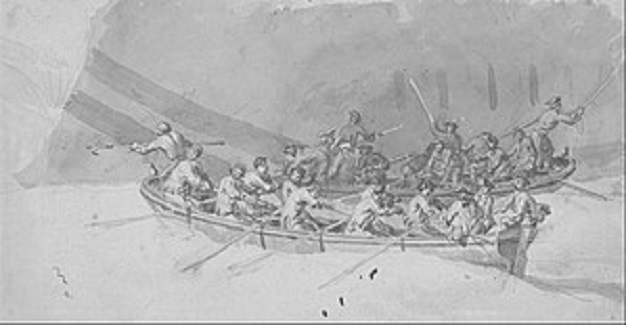

Kingsbury describes the longboat, no longer in use by 1892, as a principal carrier of heavy freight – sometimes more than 100 tons – and passengers for part of the 19th century. Longboats, he says, were from 60 to 95 feet long and 15 to 20 feet wide. They had two masts that could be lowered to go under bridges. Going downriver with the current was the easy part; to go upriver, they depended on a south wind.

Longboats were used between Augusta and Waterville until at least the 1830s. In the summer of 1832, the Ticonic was the first steamship to come upriver as far as Waterville. By 1848, Kingsbury says, there were five trips a day between Waterville and Augusta. Around that time, there was so much competition that a passenger ticket from Waterville to Boston cost only a dollar.

By 1840, after the Augusta dam eliminated the rapids as an obstacle, the Federal Writers Project Maine guide says schooners traveled weekly between Augusta and Waterville. Freight was transferred at Augusta from ocean-going ships to longboats; oxen hauled the longboats through Cushnoc rapids, walking in the river when there wasn’t room for a towpath on the shore.

Many of the ships were built locally. The Federal Writers Project guide says more than 500 ships were built in yards along the river from Augusta to Winslow in the 1800s. Merchants owned thousands of tons of shipping; it was not unusual to see 20 or so ships at Augusta wharves.

The Howard family started Augusta’s shipbuilding industry in the 1770s, according to local history, building ships that carried lumber to Boston. William Jones had a shipyard in the 1840s and 1850s; it might have been he who oversaw construction of the J. A. Thompson, built in 1849 to take easterners to the California gold rush.

The R. M. Mills, built in 1854, is described by a local source as an 800-tonner, the largest ship of the 37 ships built in Augusta between 1837 and 1856. In the dramatic account of her near-loss in the United States Register for 1860, she is listed at 673 tons.

The Mills was in the Bay of Biscay (between northern Spain and southwestern France) on her way from Ardrossan, in southwestern Scotland, to Genoa, Italy, when she started leaking. The crew of the schooner Stork saw her distress signal, and they and crew of “the Douro steamer” rescued everyone aboard, including ladies. The Stork’s passengers were taken to London, the rest to Lisbon.

The rescuers left the Mills apparently sinking on May 27. But the Register continues the story: on Tuesday, May 29, the ship Scotia from Baltimore found the Mills abandoned. The Scotia’s captain put his first mate and two crewmen on board and they brought her safely up the Thames to Victoria Dock, in London.

Vassalboro had shipyards as well. Robbins’ History of Vassalborough Maine 1771-1971 says “shipbuilding on the river” is one reason the southern part of town had enough residents by 1817 to deserve its own post office, in Benjamin Brown’s store near Seven Mile Stream. Robbins believes Vassalboro’s mail was delivered by boat on the river until 1820, when the road linking forts Western and Halifax was improved enough for stagecoaches.

Around 1850, Kingsbury describes Vassalboro entrepreneur Ira Sturgis expanding his wood-based empire that started with a sawmill and a box factory by adding a shipyard, which produced a bark, a brig and two schooners. The sawmill was on Seven Mile Stream and the shipyard nearby on the Kennebec.

In Sidney, the 1904 Belgrade and Sidney Register says there was only one shipyard (undated), at the mouth of Thayer Brook (now Goff Brook). It was owned by Willard Bailey and John Sawtelle, who also had a sawmill on the brook. The shipyard built schooners smaller than 100 tons.

In Waterville, shipbuilding started in 1794 and continued into the 1820s. In Kennebec Yesterdays, Ernest Marriner says the abundance of timber in the surrounding area helped the business flourish.

John Getchell had the first shipyard, from which the schooner Sally was launched in 1794. Marriner and Whittemore’s Centennial History of Waterville say 22 vessels came from Waterville before 1835, the largest the 290-ton Francis & Sarah, built by Robert Shaw and launched in 1814. The 178-ton brig Waterville was launched in 1825.

Shipyard owners included John Clark at the foot of Sherwin Street, next north Nathaniel Gilman, then Asa Redington and W. & D. Moor. Whittemore says the larger ships were launched during high water in spring or fall, floated down to Hallowell or Gardiner to be rigged and were never able to return to Waterville.

Kingsbury writes that Daniel Moor’s family came to Waterville in 1798. Three sons went into lumbering and boat-building; Kingsbury says they built numerous river steamers, including two they sold to Cornelius Vanderbilt.

In Winslow, Kingsbury mentions Nathaniel Dingley as a shipbuilder, as well as a lumberman and a farmer, but gives no other details.

From 1849 on, railroads along the Kennebec supplanted the waterway as a commercial route for both people and goods.

Main sources:

Federal Writers Project Maine: a Guide Down East (1937)

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed. Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

Marriner, Ernest Kennebec Yesterdays (1954)

Plocher, Stephen, Colby College Class of 2007 A Short History of Waterville, Maine Found on the web at Waterville-maine.gov.

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902)

Web sites, miscellaneous.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!