Remembering the Thanksgiving without power

/0 Comments/in Community, Holidays, Palermo/by Website Editor by Connie Bellet

by Connie Bellet

Nearly everybody who has lived in Palermo for a number of years has stories to tell about power outages (no disrespect to CMP, whose workers are heroic). However, when the power went out after the usual November storm right before Thanksgiving a few years ago, we all had to get creative. At least we can all laugh about it now.

My husband, Phil, won a large turkey at a raffle sponsored by the Palermo Community Library. Don Barrett had raised the monster bird and I think it was trying to take over his farm. It weighed in at 38 lbs. It would not fit into my oven. It would not fit into my large roaster, either. So, we called around to see if anybody would saw it in half.

The guy at Hussey’s finally said he’d do the deed. So, Phil wrapped it in a towel so he could get a better grip on it and lugged it into Hussey’s. It was like hauling a beer keg. He hoisted it onto the meat counter, amidst a number of curious onlookers. The butcher considered this a challenge, so he turned on his big band saw and grabbed the turkey’s ankles to guide it through. The band saw made some unusual noises in protest, then, almost halfway through, shrieked and ejected the saw blade.

Nobody was hurt, but there was a lot of crashing and clanging, drawing more onlookers. The butcher was now taking this personally. He carefully cleaned and remounted the band saw blade. Then he turned the turkey around and guided it in by the wings. The band saw protested, but kept going until the turkey stuck in the gateway. Only an inch or two remained. It was just too big.

Not to be deterred, the butcher decided he needed a tool to split the last inch of breastbone and spine. I thought he’d grab an axe, but nooooo. He was a real Mainer (who shall remain nameless to protect his innocence). Without an axe handy, he picked up a tire iron and stabbed it into the breastbone. It struck with a resounding crack, the turkey fell open, and the crowd went wild!

No sooner had I cleaned and brined the turkey, the power went out, and stayed out. Our next door neighbor had a generator, so he offered to plug in my roaster. I had a gas oven, which held the other half of the turkey and its stuffing, so we were good to go.

As usual, I had invited local people who didn’t have family to share Thanksgiving to join us at the Community Center. About 23 people showed up, even though we had no heat or lights. Phil collects oil lamps, so we lit several of those, and somebody brought in a space heater. Everybody brought some food, so very shortly our laughter warmed the rooms and eyes sparkled with reflected lamplight. We toasted the power company trucks as they hustled down Turner Ridge Road and in a couple of days, the power came back on and we were thankful again.

Once again, we will host Thanksgiving Dinner at 2 p.m., on Thursday, November 27. To reserve a place at the table, please call Connie at 993-2294 or email pwhitehawk@fairpoint.net. We will be delighted to welcome you.

EVENTS: Without family to share Thanksgiving? Join friends and neighbors at Palermo Community Center

/0 Comments/in Events, Palermo/by Website Editor If you have no family nearby to share the Thanksgiving Holiday, you are welcome to join friends and neighbors at the Palermo Community Center for a potluck dinner, on Thursday, November 27, at 2 p.m. There will be a roasted turkey, mashed potatoes, gravy, and fresh cranberry sauce. To prevent duplications, there is a sign-up list so we can share all our favorite dishes and make sure we have enough pies.

If you have no family nearby to share the Thanksgiving Holiday, you are welcome to join friends and neighbors at the Palermo Community Center for a potluck dinner, on Thursday, November 27, at 2 p.m. There will be a roasted turkey, mashed potatoes, gravy, and fresh cranberry sauce. To prevent duplications, there is a sign-up list so we can share all our favorite dishes and make sure we have enough pies.

Space is somewhat limited, so please call Connie at 993-2294 or email pwhitehawk@fairpoint.net, to reserve a place at the table. There is no set fee, but donations to the Living Communities Foundation are most welcome. We view Thanksgiving as a day of gratitude and sharing, so if you have a story, song, or legend to share, that would also be appreciated.

This celebration is hosted by the Community Center and the Great Thunder Chicken Drum, which honors a spirit of peace, sharing, and teaching, parts of the original Thanksgiving tradition among the early immigrants and the Native Peoples. Thus, if you choose to bring a Native American dish, that would be especially welcomed. Examples might be roasted venison, chestnut pudding, stewed blackberries, Indian pudding, or succotash. The food donation is not strictly necessary, however. Some people don’t or cannot cook, and SNAP benefits have been cut off, so the emphasis is on sharing and fellowship. You are most important. We look forward to welcoming you.

The Palermo Community Center is just off Turner Ridge Road across from the ball field. You will see our new sign as you approach Veterans Way.

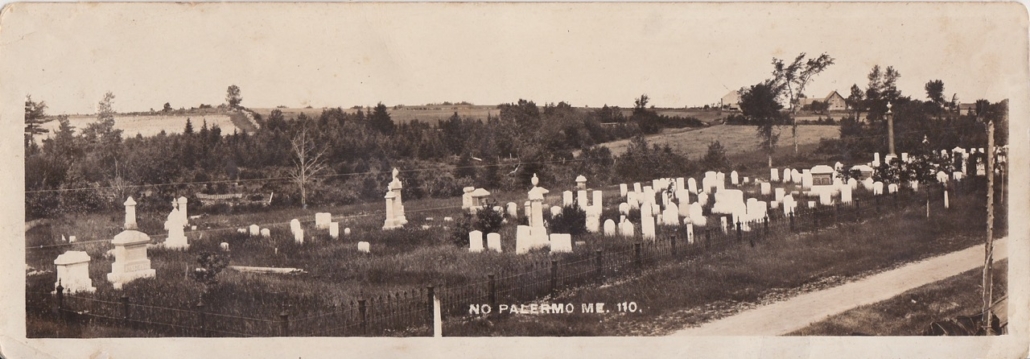

A history of Palermo’s Smith Cemetery 1825-2025

/0 Comments/in Local History, Palermo/by Andy Pottleby Andrew Pottle

2025 marks the bicentennial anniversary of Smith Cemetery on Level Hill Road in North Palermo.

Among the last of the major cemeteries in the area still operated by a cemetery association rather than the town itself, it has had an interesting history over its 200 years.

In 1807, the Town of Palermo, then just four years old, purchased its first two cemeteries: one at Greeley’s Corner for the lower half of town, and one on Dennis Hill for the upper half. By 1825, the population had grown from around 500 to almost 1,200, and the cemeteries were filling up. In 1825 the town purchased half an acre of land on what is now known as Level Hill Road for $5.50. The land was laid out in eight grave lots and sold to townspeople.

From the 1830s through the 1850s, Isaac Smith, pastor of the First Baptist Church at Carr’s Corner, lived adjacent to the cemetery. After his death in 1857, when he was buried there, it became known as Smith Cemetery.

At the end of the 1800s, the Ladies’ Improvement Society of North Palermo was formed. This group was active and successful in raising money and improving the community, with a particular focus on Smith Cemetery. In 1900, working closely with the Ladies’ Improvement Society, the Smith Cemetery Association was established. The Society sponsored many events to raise funds for the cemetery, including suppers at various homes, ice cream socials, and most notably, their highly successful annual Old Home picnic at Prescott’s Grove, located at Prescott Pond, behind the cemetery.

The Old Home Picnic was a great success, running for nearly 20 years. Hundreds of people attended each year, traveling not only from neighboring towns but also from out of state, some from as far away as New Jersey and Chicago. According to a 1910 newspaper clipping, “fully a thousand” people were in attendance that year.

A dinner was served at the picnic for those who didn’t bring their own baskets, along with a confectionery table run by Wilder Young and an ice cream table operated by Percy Turner. Anna Clark and Abbie Arnold presided over the “fancy article” table, raising funds by selling postcards of the Methodist Church, First Baptist Church, and other places of interest, as well as souvenir dishes featuring the First Baptist Church.

Manie Greeley, Mary Norton, and other women from town donated quilts and sofa pillows to be raffled off, sold, or awarded to those who correctly guessed the number of buttons in a jar.

There was music and country dancing, with some of the recorded groups including The Eureka Brass Band of Liberty, Tozier’s Orchestra of Albion, and the fiddler Charlie Overlock, of Washington.

After the first picnic in 1900, the Smith Cemetery Association was able to expand and buy land from Joel Bailey for $30. Between 1904 and 1907, $900 was raised at the picnic for the iron fence that still stands around the cemetery. Other improvements include maple trees planted in front of the fence in 1905 that lasted just over 100 years, and stone hitching posts that are still there today.

In the early years of the Association, Sanford and Manie Greeley were very active as officers of the Association, with Sanford being president for many years. They had no children of their own, but took in Kenneth Black, orphaned at eight years old, and raised him as their son until his death from tuberculosis at eighteen. When Manie died in 1940, she willed the remainder of their estate to the Cemetery Association, creating a fund of several thousand dollars for maintaining the cemetery.

In the 1940s the upkeep of the cemetery was primarily done by communal work days by lot owners. Some names of the people leading the work days include Norman Belden, Ray Nutter, Forest and Maurice Howard, and Thomas Bruso.

In 1950, M. Dewey Saban began taking on much of the responsibility for the cemetery’s care. Praised for his frugal management of the resources, including payment from families for annual care and reselling unused grave sites donated back to the Association. In 1984 a bronze plaque was placed on his cemetery lot to permanently recognize his contributions. Recently Norma Swift headed the association, until her passing in 2022, when Jamie Haskell-Spencer took over.

Most of this knowledge is owed to Palermo historian Millard Howard, who, along with nearly every name mentioned in this article, now rests at Smith Cemetery.

Sources:

Smith Cemetery Association, Milliard Howard 2013;

Newspaper archives;

Sixty-Six Years A Country Fiddler, E. Burnell Overlock 1984.

Up and Down the Kennebec Valley: Revolutionary War Veterans Windsor, Palermo, China

/0 Comments/in China, Hallowell, Local History, Palermo, Up and Down the Kennebec Valley, Vassalboro, Windsor, Winslow, Winthrop/by Mary Growby Mary Grow

This article is the last – for now – about the Revolutionary War’s effects on central Kennebec Valley towns. It again covers towns not on the river.

As previously mentioned, one effect was a post-war population increase throughout the valley, including veterans, most with families. Some of these men and their descendants became prominent in their new towns, shaping growth and development.

Missing from the historical record, at least as your writer has found so far, is all but bits and pieces of information on how the war affected its veterans. Occasionally there is a reference to a physical disability that could have been war-related.

Surely men in the 1780s suffered the equivalent of PTSD; how was it manifested, and what if anything was done about it?

When a group of veterans gathered on the porch of the general store on a warm summer day, did they one-up each other with war stories? Or was the subject forbidden?

Did a Maine veteran enjoy hunting, because he’d become an expert shot? Or was firing a gun to be avoided, because it brought back unpleasant memories?

* * * * * *

Revolutionary veteran William Halloway or Holloway is buried in Windsor, where he lived for at least some of his last 40-plus years. He was born June 18, 1747, in Bridgewater, Massachusetts; there he married Mary Molly Trask (born May 1, 1756) on June 23, 1773.

An on-line Daughters of the American Revolution site says in 1775, he bought land on a lake in Hallowell, “perhaps intending to trade in furs and timber.”

The DAR writer surmised that he changed his plans in reaction to the beginning of the war in April 1775. Another site says he enlisted in Bridgewater; the DAR writer said he sold his Hallowell land “in January 1777, while on furlough from the army.”

The website shows his hand-written pension application, in which he says he enlisted in the Massachusetts line as a private for a year in January 1776, and again for three years in the Continental service beginning in January 1777. The DAR record says he was promoted to corporal and sergeant in the Massachusetts line.

Just before his second term ended, Halloway enlisted yet again for the duration of the war. In 1782, he fell ill and was hospitalized for almost a year; then he was furloughed and sent home.

Halloway wrote that he served in “the taking of Burgoyne” at Saratoga, New York, in October 1777, and in the Battle of Monmouth, New Jersey, in June 1778, and wintered at Valley Forge.

The application is undated, but Halloway wrote that he was 71 years old, making it around 1818. He was then living in Malta, Windsor’s name from 1809 to 1820.

The DAR site says the Halloways had four sons and three daughters. The writer added that oldest son, Seth, was born “the year he left for war” (another site says 1773) and the second son, John, seven years later (Oct. 1, 1780), “bespeaking the long absence he endured from his wife and home.”

Three of the last four children were reportedly born in Maine, two in Hallowell and the last-born, Lydia, in Windsor in 1789.

Halloway died April 17, 1831, and Mary died August 11, 1844, both in Windsor.

* * * * * *

Oliver Pullen, born Oct. 17, 1759, in Attleborough, Massachusetts, was living in Palermo in 1836 (or 1835; the documents on line seem inconsistent, with a decision dated before the application was filed), when he applied for a land grant under the 1835 state law intended to benefit Revolutionary War veterans.

In his application, he said he enlisted from Attleborough in January, 1776, in a Rhode Island regiment in the continental army. He was honorably discharged in Fishkill, New York, at the end of December 1776.

In June 1777, he said, he re-enlisted as a private in the same regiment, for three years. Again, he wrote, he served the full term and took his “final and honorable discharge” July 24, 1780, near Morristown, New Jersey.

Summarizing his military service, Pullen wrote that he “was at the retreat under General [John] Sullivan from Long Island and at the battles at Long Island [August 1776] and White Plains [October 1776].” The inscription on his gravestone in Palermo’s Greeley Corner Cemetery Old says he served in Colonel Henry Sherman’s regiment.

(Palermo has two Greeley Corner cemeteries close together on Route 3, opposite the Second Baptist Church, where on-line maps show the intersection of Route 3 and Sidney Road. Find a Grave calls them “Old” and “New” with the adjective at the end of the name.

(Millard Howard wrote in his Palermo history that the town bought the land for the first cemetery in 1807. An on-line photo of its sign dates New Greeley Cemetery 1901.)

Pullen’s petition was rejected. A note says he “Did not serve three years”: under it is another note, “35 m 20 d.”

FamilySearch says Pullen married Abigail Page (born in 1761, per WikiTree, or 1767, per FamilySearch) in July 1782, in Vassalboro. They had at least four sons, this source says.

Sargent Sr., was born Jan. 9, 1784, in Winthrop, when – by FamilySearch’s dates and math – his father was 24 and his mother was 17. Gilbert was also born in 1784, apparently later, as his father’s age is listed as 25 and his mother’s as 17; his birthplace was Palermo. Stephen Sr., was born in 1786, in Palermo. Montgomery A. was born in 1794, no birthplace given.

Howard listed Gilbert Pullen as one of the privates in the Palermo militia unit that marched to Belfast in September 1814 to meet a threatened British attack during the War of 1812.

FamilySearch says Oliver Pullen was in Winslow in 1800 and in Waterville in 1810 (the part of Winslow that was on the west bank of the Kennebec River became Waterville in June 1802, so he probably changed towns without moving).

Abigail Pullen died in 1803, aged 36, FamilySearch says; WikiTree says she lived until Jan. 2, 1857, and died in Attleboro, Massachusetts. FamilySearch’s report that she is buried in Readfield, Maine, almost certainly confuses her with another woman.

Oliver Pullen died Dec. 8, 1840, according to his gravestone. Abigail is not among the 10 other Pullens buried in Palermo’s Greeley Corner Cemetery Old. Gilbert and his wife, Nancy (Worthing) Pullen seem to be the only members of the second generation.

* * * * * *

In addition to Abraham Talbot, profiled last week, two more black Revolutionary veterans are reportedly buried in China, Luther Jotham and his younger brother, Calvin Jotham.

An interesting on-line National Park Service article, in the form of a story map titled “Luther Jotham: A Journey for Country and Community” summarizes Luther’s life, including his Revolutionary service. The author began by saying that his record sounds like that of a typical Massachusetts militia man, who trained regularly to be ready for an emergency – except that before the Revolution, Massachusetts law prohibited Blacks from training in peacetime.

The writer said Jotham was born about 1759, in Middleborough, Massachusetts. His parents moved the family to Bridgewater, Massachusetts, before the Revolution, perhaps for better job opportunities.

After the December 1773 Boston Tea Party and the British occupation of the city, Bridgewater, like many other towns, organized a volunteer Minute Man company. Free Blacks were allowed to join, and Jotham did.

The writer pointed out that his motives might have included the stipend (one shilling for each half day of training) or the hope of improving his “social standing” in the mostly-white town.

The Bridgewater troops’ first quasi-military experience was in April 1775, when British forces moved from Boston to Lexington and Concord and met American resistance. The writer explained that in January 1775, British General Thomas Gage had sent troops to Marshfield, a Loyalist town about 30 miles southeast of Boston and about 20 miles northeast of Bridgewater. Militia units, including Bridgewater’s, marched to Marshfield, but did not attack.

On Aug. 1, 1775, Jotham enlisted in the Plymouth County militia and served for five months, stationed in Roxbury, Massachusetts, near Boston. He enlisted again as a militia man in January 1776; came home briefly in April; and re-enlisted in the summer of 1776.

During this period, he was for the first time involved in fighting. The website writer said his unit was in the Battle of Harlem Heights in September and the Battle of White Plains in October. When his enlistment expired Dec. 1, 1776, he again returned to Bridgewater.

Jotham enlisted for the fourth and apparently last time in October 1777. He served only briefly, because, the writer said, militia units were sent home after General Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga on October 17.

Back in Bridgewater, Jotham married for what the writer said was the first time and WikiTree says was the second time. WikiTree names his first wife as Elizabeth Cordner, whom he married Sept. 24, 1774, and who died in or around 1777.

The sources agree he married Mary Mitchel, born about 1755; WikiTree says the wedding was April 8, 1778, in Brockton. According to the National Park Service writer, the couple had three children, Lorania, Lucy, and Nathan.

In January 1779, this source says, Jotham bought 15 acres of land, thereby changing his status (in town records, apparently) from “labourer” to “yeoman,” that is, a “man who farmed his own land” instead of working for other people.

The writer found that Jotham’s life was not easy, at least partly because of his race. In November 1789, he and his family, and his brother Calvin, were among “scores of… working class families” whom the town selectmen ordered to leave town – a practice called “warning out,” used to get rid of residents seen as likely to become paupers in need of town support.

In the early 1800s, Jotham did leave town, moving his family to Vassalboro, Maine, for unknown reasons. There he bought 20 acres of land.

By 1818, when he applied for a pension as a Revolutionary veteran, his resources had dwindled. He wrote that his possessions included “a house, small hut, a few tools and household items.” He had “one cow, three sheep, and one pig.”

He claimed an annual income of less than five dollars, and added: “I am by occupation a labouring man but from age and infirmity unable to do but little.” An annual pension of $96 was approved in 1820.

The National Park Service writer said that Jotham’s wife Mary and all three children died in Vassalboro. In 1816, he married Reliance Squibbs (his second wife in this account, not mentioned by WikiTree), by whom he had two more children, Mary Anne and Orlando. Reliance died before Jotham got his pension in May 1820, and a witness to his application said the two children had also died.

On Dec. 20, 1821, in Vassalboro, Jotham married a woman named Rhoda Parker. Rhoda, listed as a mulatto in the 1850 census, was born in 1787 in Georgetown.

Find a Grave says she and Jotham had at least one son, born in Vassalboro in 1829 and named Calvin (after his uncle). The Park Service writer said there were at least three children of this marriage.

(The younger Calvin Jotham died Dec. 17, 1883, in Sherbrooke, Québec, where he and his white wife had a daughter and three sons between 1863 and 1880.)

By August 1827, Jotham was considered to need a guardian to manage his affairs, and a man named Abijah Newhall was appointed. Not long afterwards, the family moved to China, where Jotham died June 2, 1832, aged 81.

Rhoda applied for a widow’s pension in 1860. She died in October 1869, in China. Find a Grave says by then her last name was Watson; apparently she remarried after Jotham’s death.

Your writer found much less information about Luther Jotham’s brother, Calvin, and no details about his military service.

Find a Grave says he was born in 1759 in Middleborough, Massachusetts. He died in March 1841 in China and is buried in the town’s Talbot Cemetery. This site says he fathered a daughter and a child who died in infancy, both in Brockton, Massachusetts; it names no wife.

Main sources

Howard, Millard, An Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine (second edition, December 2015)

Websites, miscellaneous.

Palermo residents should expect surveys in mail

/0 Comments/in Community, Palermo/by Website Editor The Conservation Committee will soon be mailing out a survey to Palermo residents to gather input on commercial solar arrays and commercial wind farms. Copies of the survey will also be available at the town office, and accessible online via a link on the Town’s website. Please watch for this survey, fill it out and return it so we can know the opinions of Palermo citizens on these issues. For more information, contact Chairman Gordon Hunt at 207-993-2005.

The Conservation Committee will soon be mailing out a survey to Palermo residents to gather input on commercial solar arrays and commercial wind farms. Copies of the survey will also be available at the town office, and accessible online via a link on the Town’s website. Please watch for this survey, fill it out and return it so we can know the opinions of Palermo citizens on these issues. For more information, contact Chairman Gordon Hunt at 207-993-2005.

Community Cookout gathers folks for fun and food

/0 Comments/in Community, Palermo/by Website Editorby Connie Bellet

A perfect mid-October afternoon in and around the grape arbor brought neighbors and friends together to enjoy plentiful food, laughter, and entertainment. Three pitmasters kept the steam tables full of freshly grilled chicken, pork steaks, brats, burgers, and hot dogs. Neighbors and volunteers brought their specialty dishes, and a Japanese Taiko Drum group performed with choreographed skill.

The barbecue was a fundraiser for the Palermo Community Center to celebrate and thank their volunteers, who dedicated many hours of service to the Palermo Food Pantry and the Community Center. The barbecue raised over $680.

PUBLIC NOTICES for Thursday, October 23, 2025

/0 Comments/in Legal Notices, Palermo/by Website EditorTOWN OF PALERMO

NOTICE OF PUBLIC HEARING

GENERAL ASSISTANCE ORDINANCE

The Town of Palermo will be holding a Public Hearing at the Palermo Town Office, 45 North Palermo Road, at 6 p.m., on Thursday, October 30, 2025. This will be to review the proposed ordinance. The General Assistance Ordinance from September 2025 With 2025/2026 Appendices.

***

TOWN OF PALERMO

SPECIAL TOWN MEETING

The Town of Palermo will be holding a special Town Meeting on October 30, 2025, at 6:00 PM, at the Town Office. Shall the Town Vote to change the Road Commissioner’s elected term to 3 years effective the 14th day of March, 2026.

***

STATE OF MAINE

PROBATE COURT

COURT ST.,

SKOWHEGAN, ME

SOMERSET, ss

NOTICE TO CREDITORS

18-A MRSA sec. 3-804

The following Personal Representatives have been appointed in the Estates noted. The first publication date of this notice October 23, 2025. If you are a creditor of an Estate listed below, you must present your claim within four months of the first publication date of this Notice to Creditors or be forever barred.

You may present your claim by filing a written statement of your claim on a proper form with the Register of Probate of this Court or by delivering or mailing to the Personal Representative listed below at the address published by the Personal Representative’s name a written statement of the claim indicating the basis therefore, the name and address of the claimant and the amount claimed or in such other manner as the law may provide. See 18-C M.R.S. §3-804.

2025-293 – Estate of DAVID H. TURNER, SR., late of Palmyra, Maine deceased. David H. Turner, Jr., 4046 Woodview Dr., Sarasota, FL 34232 appointed Personal Representative.

2025-295 – Estate of FRED O. MATHIEU, late of Moscow, Maine deceased. Crystal L. Brown, P.O. Box 8, Athens, ME 04912 appointed Personal Representative.

2025-296 – Estate of BOBBI JO SANDS, late of Pittsfield, Maine deceased. Klaire Z. Magaera, 2603 W. Fawn Dr., Phoenix, AZ 85041 appointed Personal Representative.

2025-298 – Estate of JUDY A. CLARK-FOSTER, late of Skowhegan, Maine deceased. Gretchen L. Clark, 467 Middle Rd., Skowhegan, ME 04976 appointed Personal Representative.

2025-300 – Estate of LOREN P. BUTLER, late of St. Albans, Maine deceased. Christopher M. Pepin, P.O. Box 216, Orrington, ME 04474 appointed Personal Representative.

2025-308 – Estate of RICHARD A. FRAZIER, late of Madison, Maine deceased. Catherine S. Frazier, 141 Park St., Madison, ME 04950 appointed Personal Representative.

2025-309 – Estate of RICHARD J. SCHLEIER, late of Starks, Maine deceased. Cindy Laney, P.O. Box 87, Anson, ME 04911 appointed Personal Representative.

2025-310 – Estate of HELMA R. CURTISS, late of Madison, Maine deceased. Angela McAlpin, 21867 Knobb Hill Pl., Ashburn, VA 20148 appointed Personal Representative.

2025-311 – Estate of FRANCES A. GORDON, late of Bingham, Maine deceased. Barry Gordon, 2303 Kennebec River Rd., Concord Twp., ME 04920 appointed Personal Representative.

2025-312 – Estate of EUGENIA M. DEERING, late of Ripley, Maine deceased. Liza M. Tighe, P.O. Box 345, St. Albans, ME 04971 appointed Personal Representative.

2025-313 – Estate of CHARLENE N. FOURNIER, late of Bingham, Maine deceased. Dodi L. Mingo, P.O. Box 174, Bingham, ME 04920 appointed Personal Representative.

2025-314 – Estate of CECILE M. VIGUE, late of Fairfield, Maine deceased. Patricia L. Bolduc, 2 Forest Park, Waterville, ME 04901 and Robert A. Vigue, P.O. Box 114, Mapleton, ME 04757 appointed Co-Personal Representatives.

2025-315 – Estate of GARY O. MCPARTLIN, late of Fairfield, Maine deceased. Neal McPartlin, 331 Water St., Hallowell, ME 04347 appointed Personal Representative.

2025-316 – Estate of JOSEPH L. LEMIEUX, late of Fairfield, Maine deceased. Bernadette LaCroix, 156 East Side Trail, Oakland, ME 04963 appointed Personal Representative.

TO BE PUBLISHED October 23, 2025 & October 30, 2025

Dated: October 23, 2025 /s/Victoria M. Hatch,

Register of Probate

(10/30)

STATE OF MAINE

PROBATE COURT

41 COURT ST.

SOMERSET, ss

SKOWHEGAN, ME

PROBATE NOTICES

TO ALL PERSONS INTERESTED IN ANY OF THE ESTATES LISTED BELOW

Notice is hereby given by the respective petitioners that they have filed petitions for appointment of personal representatives in the following estates or change of name. These matters will be heard at 10 a.m. or as soon thereafter as they may be on November 5, 2025. The requested appointments or name changes may be made on or after the hearing date if no sufficient objection be heard. This notice complies with the requirements of 18-C MRSA §3-403 and Probate Rule 4.

2025-301 – JESSICA LEIGH DAVIS. Petition for Change of Name (Adult) filed by Jessica Leigh Davis, 40 Silver St., Skowhegan, ME 04976 requesting her name to be changed to Jesska Leigh Moody for reasons set forth therein.

2025-304 – KIRSTIE LEE KRUKOWSKI HALE. Petition for Change of Name (Adult) filed by Kirstie Lee Krukowski Hale, 86 Pleasant St., Moose River, ME 04945 requesting her name to be changed to Kirstie Lee Krukowski for reasons set forth therein.

2025-307 – GAVIN MICHAEL GERVAIS. Petition for Change of Name (Minor) filed by Megan Roy, 41 Norridgewock Ave., Skowhegan, ME 04976 requesting minor’s name to be changed to Gavin Michael Roy for reasons set forth therein.

Dated: October 23, 2025

/s/ Victoria Hatch,

Register of Probate

(10/30)

EVENTS: Palermo Community Cookout coming Saturday, October 11, 2025

/0 Comments/in Events, Palermo/by Website Editor Submitted by Connie Bellet

Submitted by Connie Bellet

The weather report for October 11 looks great, with Indian Summer gracing us with autumn warmth. This is the perfect time to kick back and enjoy some wonderful food and camaraderie with friends and neighbors in a backyard setting beneath a real grape arbor and some shady shelters. The fragrance of roasting meats over a charcoal fire whets our appetites as the Palermo Community Center and the Great ThunderChicken Drum welcome everyone to the feast. Some of Palermo’s best cooks will share a buffet of salads, beans, roasted turkey, chicken, pork, and brats in a beer hot tub (child friendly) and, of course, seasonal pies and crisps. Tickets are only $12.00 for people over age 12, with smaller kids free. Takeout is also available. The fun and food commence at 1:30 pm., and there is plenty of parking behind the grape arbor. The Community Center is at the corner of Turner Ridge Rd. and Veterans Way. A left turn behind the Center at the wood shed will lead down a pathway to the parking area.

Following the feast, Don Kealey will enliven the crowd with the raffle drawing. The prizes include serious garden tools donated by The Home Depot, potting soil and fertilizer from Annie Frier and Sandy Davis, a bird feeder and seed from Ruth Flint, and a backyard firepit from Ann and Peter Bako. There are also some nice wall décor pieces from Nancy and Dawn Beekley, with some other intriguing items still arriving. Then, there will be entertainment! A Japanese Taiko Drum group of young adults and their sensei will make sure nobody drifts off on a full stomach.

This is a celebration honoring our volunteers, who have put in many long hours working on the grounds, placing a new sign on Turner Ridge Road. The Food Pantry volunteers have been serving neighbors in need every week for the last 14 years. The Great ThunderChicken Drum has brought inspiration, cultural wisdom, and song to many hearts since 2008, and the Community Garden provides hundreds of pounds of very fresh, organic produce to the Food Pantry. The Community Foundation thanks AARP and Community Connections for a grant of $3,700 for the road sign, and SeedMoney.org for a grant of $2,150 for the Community Garden. Thanks also go to Hannaford for their contribution of meat for the feast!

Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Revolution effects

/0 Comments/in Albion, China, Local History, Palermo, Up and Down the Kennebec Valley, Vassalboro, Windsor, Winthrop/by Mary Growby Mary Grow

The American colonies’ war for independence from Great Britain had only limited effects in the central Kennebec Valley. With one important exception (to be described in September), no Revolutionary “event” occurred in this part of Maine. No battles between armies were fought here, although there were some between neighbors and, most likely, among family members.

Many men (your writer found no recorded women) enlisted or were drafted, leaving wives and children to run a farm or business. The war’s economic effects, like taxes, high prices and shortages, percolated this far north, though probably they were less damaging in a mainly agricultural area than in coastal Maine.

One major consequence, however, was the effective elimination of the Kennebec or Plymouth Proprietors. That Boston-based group of British-descended, and often British-leaning, businessmen lost most of its influence in the Kennebec Valley by the end of the war, as Gordon Kershaw explained in his 1975 history, The Kennebeck Proprietors 1749-1775.

The historian summarized two changes wrought by the war and American independence. First, he said, the Proprietors became divided, with many putting other interests ahead of the company’s.

Among the Proprietors were several whose names are familiar today. One who decided to join the rebellion was James Bowdoin, II, the man for whom Maine’s Bowdoin College was named in 1794.

Dr. Sylvester (Silvester) Gardiner, Benjamin Hallowell (and family) and William Vassall all had riverine towns named in their honor. They chose the British side in the 1770s, Kershaw said, as did most family members (except Briggs Hallowell, one of Benjamin’s sons whom Kershaw called “a maverick Whig in a family of Tories”).

Kershaw wrote that several Proprietors, including Bowdoin, Gardiner and Vassall, continued to meet until March 1775. Gardiner and Hallowell holed up in Boston and left for Halifax, Nova Scotia, when the British evacuated the city on March 17, 1776. An on-line source says Vassall went to Nantucket in April 1775 and in August to London, where he spent the rest of his life.

The second change, Kershaw wrote, was that the settlers on the Kennebec took advantage of American independence to ditch not only British control, but control by the Proprietors.

During the Revolution, he said, a group led by Bowdoin and others tried to meet 25 times. Fourteen meetings failed to muster a quorum, and at the other 11, “no important business was transacted.” But after the 1783 Treaty of Paris ended hostilities, the Whig members reactivated the company.

By then, two developments in the Kennebec valley challenged long-distance control. The first local governments had been established, Hallowell, Vassalboro and Winslow (and Winthrop) in 1771, and local leaders and voters were making more and more decisions, especially imposing property taxes to support development. The taxes fell most heavily on the largest landowners, often the Proprietors.

The second development was that during and especially after the war, new settlers, including veterans, moved into the area.

“They sought out the land they wanted, and occupied it. Later, many dickered with the Company for titles,” Kershaw wrote. Others rejected Company claims.

The Kennebec Proprietors continued to make land grants after the Revolution, including in Whitefield, Winthrop and Vassalboro in 1777. They continued to try to deal with settlers who did not have, and often did not want, titles from them. Violence sometimes resulted, including the “Malta War” in 1808.

A few years later, Kershaw wrote, a Massachusetts commission reviewed disputed properties between the Proprietors and the settlers. Its report, approved by the legislature on February 23, 1813, gave the settlers all their land; and in compensation, gave the Proprietors Soboomook (Sebomook) township, north of Moosehead Lake.

Kershaw saw this decision as fair to the settlers, many of whom had made major improvements on their land and who, had the Proprietors gotten it, would have had to pay more money than backwoods people were likely to have.

It was less fair to the Proprietors, he thought: developing their new property would have been expensive and probably unprofitable. The main thing they gained was “the satisfaction of knowing that a festering disagreement had been settled at last.”

Kershaw surmised that the 1813 ruling was the final straw that led the Kennebec Proprietors to disband. In June 1815, he wrote, they voted to sell their remaining land at auction on Jan. 22, 1816 – including lots in Augusta, Waterville, Albion, China, Palermo and Windsor.

The sale was duly held, bringing in more than $40,000. Other business was completed in following years; and on April 26, 1822, “the books of the Kennebec Purchase Company were closed forever.”

* * * * * *

Local historians paid varying amounts of attention to the Revolutionary War’s effects on their towns and cities. James North, in his 1870 history of Augusta, devoted about 45 pages to the years between 1774 and 1783, writing partly about the Revolution and partly about local developments.

North was an unabashed supporter of the Revolution. By the spring of 1776, he wrote, the British colonies’ residents “had attained to that state of feeling which precluded all hope of reconciliation, and made exemption from colonial servitude a primary law of political existence.”

“Unequal as the contest for independence was seen to be, the great body of the people readily committed themselves to it, with full determination to undergo its sufferings and brave its dangers.”

The Tory minority, whom North described as “connected with the long established order of affairs,” soon realized they were witnessing “the efforts of a great people struggling with hardy enterprise, under unparalleled difficulties, of individual freedom and national existence.”

Henry Kingsbury, in his Kennebec County history, was also on the revolutionaries’ side. He mentioned the March 5, 1770, Boston Massacre (when seven British soldiers, facing angry Bostonians, fatally shot five of them and wounded others) as the first event that “sent a thrill of horror up the Kennebec,” despite the miles of wilderness between Boston and the river settlers.

North’s account of Revolutionary events began with the Boston Tea Party on Dec. 16, 1773, and the British retaliatory measures in the spring of 1774, which led to first steps toward creating local Massachusetts authorities to replace the British government.

“These ominous events aroused the sturdy yeomen of ancient Hallowell to patriotic action,” Kingsbury wrote. But he and North agreed that a strong Tory presence – mostly from the Plymouth Company, in Kingsbury’s view – frustrated early reactions.

At a Provincial Congress in Massachusetts that assembled Oct. 7, 1774, and adjourned Dec. 10, North wrote that Gardinerstown Plantation, Winthrop and Vassalboro were represented (the last by a leading citizen named Remington Hobby or Hobbie). No one went from Hallowell, North said, “probably through tory influence which may have paralyzed action.”

Hallowell residents began redeeming themselves early in 1775. In response to a Provincial Congress call to organize for defense, they held a town meeting at 9 a.m., Wednesday, Jan. 25, “to choose officers and to form ourselves in some posture of defence with arms and ammunition, agreeable to the direction of congress” (North’s quotation from the warrant calling the meeting).

North noted that this meeting, for the first time, was not called in the name of His Majesty, the King of Britain.

North said no records of the meeting have been preserved, perhaps because of Tory influence. That influence was also shown at the annual town meeting later in the spring, when voters elected surveyor and Loyalist John “Black” Jones as constable (see the July 24 issue of The Town Line for more on Jones). They promptly rescinded the vote – and then elected him again.

A month later, North reported, Jones had hired a replacement, confirmed at another town meeting. But this same meeting’s voters chose him as a member of a five-man committee, one of whom was to represent Hallowell at a “revolutionary convention” scheduled in Falmouth.

Kingsbury wrote that early 1775 actions included forming a military company and a safety committee. The latter consisted of “principal citizens” and was given “charge of all matters connected with the public disorder, including correspondence with the revolutionary leaders.”

In Kingsbury’s view, “A town of so few inhabitants, however willing, could not give much aid to the continental cause, and its part in the war was necessarily small and inconspicuous.” (Later, he wrote that in 1777 or 1778 Hallowell had only about 100 heads of families listed on its voting rolls.)

North’s account of the early days of the Revolution focused on local issues. Beyond the Kennebec Valley area, Massachusetts organized three provincial congresses in the Boston area: the first from Oct. 7 to Dec, 10, 1774; the second from Feb. 1 to May 29, 1775; and the third from May 31 to July 19 (“a month after the battle of Bunker Hill”). North wrote that Hallowell voted not to send a representative to the third congress; he was silent on participation in the first two.

However, when Massachusetts officials decided to re-establish their legislature, the Great and General Court, and hold a July 19, 1775, session, Hallowell voters elected Captain William Howard their representative.

North said local and provincial government had been pretty much suspended. The new Massachusetts legislature effectively recreated it, including organizing the militia and issuing paper money.

The Continental Congress was doing the same for a national government. Its achievements included renewing mail delivery “from Georgia to Maine” – but only as far as Falmouth, Maine.

Hallowell people got their “letters and news” by ship as long as the river was ice-free. In the winter, North wrote (quoting Ephraim Ballard, who quoted his mother’s account), for several years residents near Fort Western got mail brought “from Falmouth by Ezekiel and Amos Page, who alternately brought it once a month on snow shoes through the woods.”

(North earlier named Ezekiel Page and his 17-year-old son Ezekiel as moving from Haverhill, Massachusetts, to Cushnoc in 1762; the family took two lots on the east bank of the Kennebec. WikiTree says the senior Ezekiel was born in May 1717 and died about March 1799; he and his wife, Anne Jewett [born in October 1725] had five sons, including Ezekiel [born April 30, 1746, in Haverhill; died May 10, 1830, in Sidney, Maine] and Amos [born July 13, 1755, in Hallowell; died Dec. 26, 1836, in Belgrade, Maine] and four daughters.)

The major events of 1776, in North’s view, were the British evacuation of Boston in March, “to the great joy of the eastern people,” and the signing of the Declaration of Independence in July. The Massachusetts government had copies of the Declaration sent to every minister in the state and required each to read it to his congregation the first Sunday he received it.

Kingsbury put more emphasis than did North on how hard the war was on Hallowell. He said that “its growth was retarded and well-nigh suspended,” as the wealthy proprietors abandoned their holdings. His major piece of evidence:

“So great was the depression that even the Fourth of July Declaration was not publicly read to the people.”

By 1776, North said, other instructions from Massachusetts officials made service in the militia compulsory for all able-bodied men between 16 and 60. Anyone who refused to serve was fined, and if he did not pay promptly, jailed.

Lincoln County raised two regiments whose companies drilled regularly. North wrote that some of the enlistees were on an “alarm list,” “minute men” who could assemble “on occasions of sudden alarm.”

North summarized the 1777 equipment of one 26-man company based on the west bank of the Kennebec: it included 15 guns, five pounds of powder and 107 bullets. The bullets were shared among seven people — but some of the seven had neither guns nor powder.

To be continued next week

Main sources:

Kershaw, Gordon E., The Kennebeck Proprietors 1749-1775 (1975)

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870)

Websites, miscellaneous.