REVIEW POTPOURRI: Ralph Vaughan Williams, Stephen King & Calvin Coolidge

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates

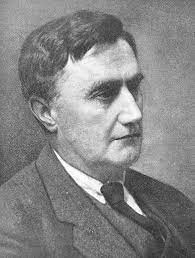

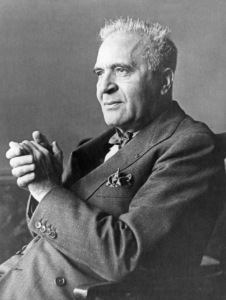

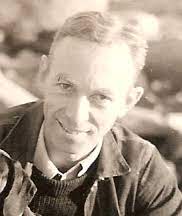

Ralph Vaughan Williams

I first became attracted to the music of English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) back during high school when I heard a recording of his London Symphony at a friend’s house and shortly after ordered it by mail from King Karol Records in New York City, now long closed.

The London Symphony was composed in 1920, is the second of his Nine Symphonies and is a celebration of the panoramic beauty of London. He used the full orchestra to convey its sights and sounds – the early morning awakening of the city, the streetcars and trolleys rushing its citizens to work, the hush of quiet side streets during the afternoon lull and at twilight, and the movement of ships down the Thames River towards the ocean. The Big Ben Clock chimes its 12 notes at the end of the Symphony in an exquisite manner.

The Barbirolli recording is available on YouTube.

Other works of VW well worth hearing include the other eight symphonies, especially the 1st or Sea Symphony for chorus and orchestra, the 3rd Pastoral Symphony, Symphonies 5 and 6 from the World War II decade. His ballet Job, the operas Pilgrim’s Progress, the Lark Ascending for violin and orchestra and his arrangements of English hymns and folk songs, etc. All on YouTube.

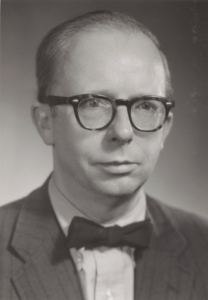

Stephen King

Maine’s own Stephen King’s latest novel Billy Summers deals with a hit man who only shoots truly bad guys. The story line deals with a two million dollar contract in front of a heavily guarded courthouse and the … but enough said.

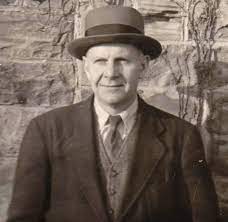

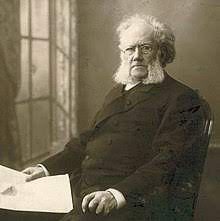

President Calvin Coolidge

YouTube also has several news reels showing former President Calvin Coolidge (1872-1933) at work and on vacation. Because he was very gifted with managing the government with low taxes and a man of few words, he would be worthy of further study by those currently in power.