REVIEW POTPOURRI: Mozart

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates

Mozart

Divertimento, K. 563-

Pasquier Trio; Columbia Masterworks, M-351, recorded 1935, six 12-inch 78s.

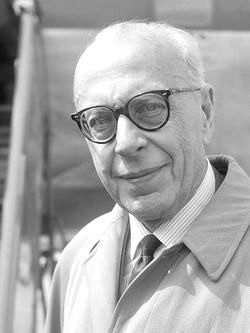

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) composed his one and only String Trio for violin, viola and cello in 1788 for a friend/benefactor Johann Michael Puchberg but the circumstances are unknown. The total number of his works are over 600; this piece appeared after his final three symphonies, 39, 40 and 41 or the Jupiter (all 3 composed in 6 to 8 weeks.).

The Trio is, like so many Mozart pieces, a masterpiece from one extraordinary genius who composed his first Symphony at four years old. Still to come in his three remaining years were the 27th Piano Concerto, Magic Flute and Requiem and about 60 other pieces before his death from a variety of health problems mainly related to overwork and alcoholism.

The Pasquier Trio consisted of three French-born brothers – violinist Jean, violist Pierre and cellist Jean – who recorded several works during the 78 era. The above set can be heard on YouTube and is a superb performance.

The 1985 movie Amadeus gives a basically twisted portrayal of the composer from the point of view of his arch-rival Salieri but it is quite entertaining and brimming with his music. Another recommendation is Swedish director Ingmar Bergman’s 1975 cinematic treatment of The Magic Flute, which I have seen at least five times.

YouTube has just about every piece of the composer in many historical and current recordings.

Biographical accounts of the composer describe him as vain about his wavy hair, not particularly striking in physique or poise, working long hours under financial pressures, and quite fond of billiards and dirty jokes.

In recent weeks, I have been listening to recordings of his Abduction from the Seraglio, C Minor Mass and Violin Concertos, all of which I recommend as good starting points for those new to the composer, but I might be quite biased.

The very witty Jim Thompson (1906-1977) wrote in his memoir, Bad Boy, about his maternal grandfather ‘Pa’ as a Robin Hoodish personality who gave generously to the less fortunate but thought little of chiseling the rich, stating “that they had probably stolen their money anyway and that he could put it to better use than they could.”