Waterville City Hall

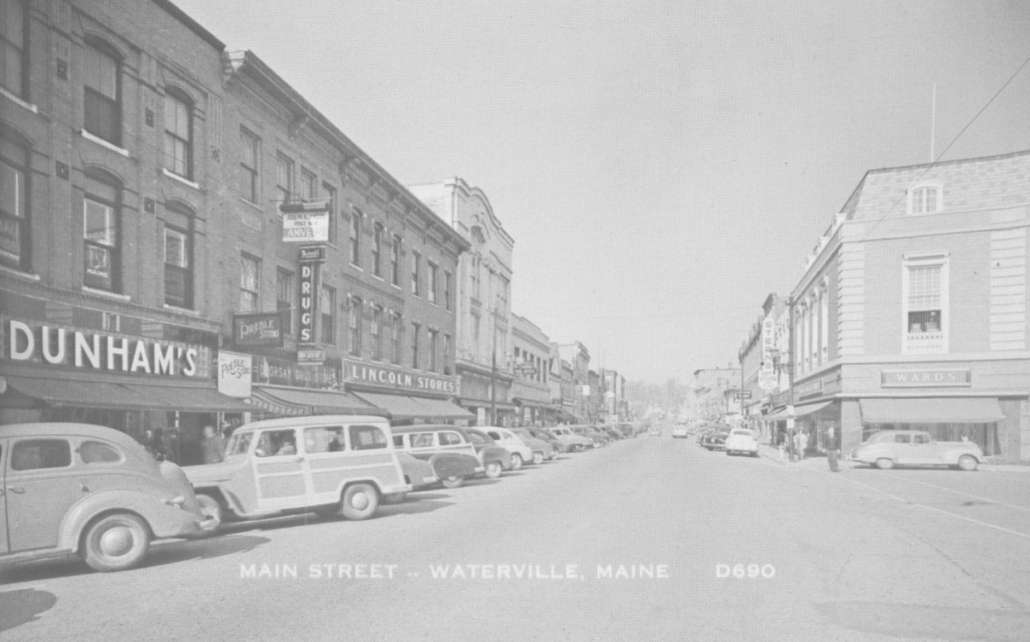

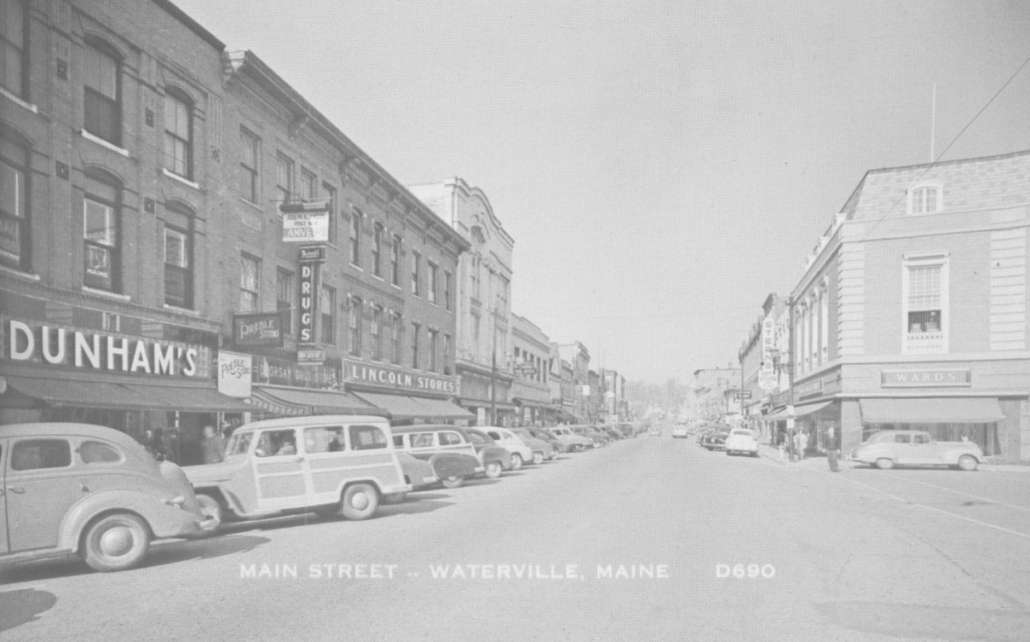

As sources cited in this and the following articles say, Waterville’s downtown business district was in the 19th and 20th centuries (and still is in the 21st century) an important regional commercial center. Buildings from the 1830s still stand; the majority of the commercial buildings lining Main Street date from the last quarter of the 19th century. Hence the interest in recognizing and protecting the area’s historic value by listing it on the National Register of Historic Places.

Waterville’s original downtown historic district, according to the initial application for historic listing in 2012, includes 22 historic buildings and three others too new to count as historic; two “objects” (in Castonguay Square) one “structure” (the information kiosk in the square, too modern to count) and two public parks, Castonguay Square and the Pocket Park on the north side of the Federal Trust Bank building.

The district runs from the intersection of Temple and Main streets south to the connector to Water Street at the south end of Main Street, covering both sides of Main Street. It includes both sides of Common Street, encompassing the Opera House and City Hall building that had been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1976.

In 2016, the district was extended northward on the east side of Main Street for another block, from Temple Street to Appleton Street. This additional section of the historic district will be described in a later article.

The 2012 application for historic register listing was prepared by Matthew Corbett and Scott Hanson, of Sutherland Conservation and Consulting, in Augusta. The document lists Main Street buildings from north to south on the east (river) side of the street, with a detour down Common Street, and from south to north on the west side. The names of some of the businesses will be familiar to those who knew Waterville 11 years ago and earlier.

Almost all the buildings share common walls to form a solid façade. Most extend directly to the sidewalk, creating what the application describes as a “canyon effect” that was destroyed north of Temple Street by the demolition of west-side buildings in a 1960s urban renewal project.

Because so many of the street-level entrances have been modernized over the years, the more historically interesting parts of the building facades are from the second floor upward. Corbett and Hanson listed details of windows, trim and other features for each building.

Arnold-Boutelle-Elden Block

On the east side of Main Street, the northernmost building in the original district, on the south corner of Main and Temple streets, is the Arnold-Boutelle-Elden Blocks (103-115 Main Street, according to the application). It consists of six store fronts with common walls, the first four built in 1886 and 1887 and the last two in 1893. The application describes the three-story buildings as Queen Anne style and describes in detail the decorative elements in granite and brick. Names and dates are carved in granite plaques “in the pediments of the second, third, and fifth blocks.”

Next south was what was in 1912 the Hanson, Webber & Dunham Hardware store, built in 1894. Four stories high, brick with granite sills and brick arches, topped by a “decorative cornice flanked by two small corbelled brick piers,” the application says it was once owned by Central Maine Power Company.

In 1902, according to Frank Redington’s chapter on businesses in Edwin Carey Whittemore’s Waterville history, the blocks from Arnold to Hanson, Webber & Dunham, inclusive, had been remodeled to form “an unbroken front.” From there to Castonguay Square there were only wooden buildings in 1902.

The wooden buildings were succeeded by the three-story brick Montgomery Ward Department Store building at the corner of Main Street and Castonguay Square, originally built in 1938 and expanded northward in 1967 (when it took over what the application calls the Stearns commercial block and your writer remembers as Sterns department store). The building is Georgian Revival style; Corbett and Hanson’s application says Montgomery Ward used it from 1933 to 1948.

Montgomery-Ward

Corbett and Hanson wrote that what is now Castonguay Square was part of a parcel deeded in 1796 from Winslow (which until 1802 included Waterville) “to be used for church/meetinghouse and school house.” Both buildings were put up, and the meeting house later became the town hall, with an adjoining area of open space with trees, “at one point, bounded by a wooden fence.”

Redington wrote that local boys used to call the square “the hay scales.” He did not explain.

In the early 20th century the town hall became City Hall and the park became City Hall Park. It became Castonguay Square in 1921 to honor First Sergeant Arthur L. Castonguay, killed in World War I.

Stephen Plocher wrote in his on-line Waterville history that more than 500 men from Waterville served in World War I, and Castonguay was the first to die. Another on-line source suggested that he was among National Guard members who became part of the 103rd infantry, a unit that fought in major battles in France.

The two historic objects in the square are unrelated. An inscription on a round boulder, a 1917 gift from Silence Howard Hayden Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, commemorates Benedict Arnold’s 1775 march to Québec. A “German 15 cm heavy field howitzer model 1893” is probably one of the captured weapons distributed nation-wide by the United States Department of Defense in the 1920s.

* * * * * *

On the north side of the square stands the combined Opera House and City Hall, with an address of 1 Common Street. This building has been on the National Register of Historic Places since the beginning of 1976; the application for listing was prepared in October 1975 by Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., and Frank Beard of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

The application calls the building “a good representative example of the multi-purpose civic buildings erected in Maine at the turn of the century.” The idea came from a May 1896 citizens’ petition to the Waterville mayor and board of aldermen.

City officials chose George G. Adams, of Lawrence, Massachusetts, as architect, and in February 1897 signed a building contract with another Massachusetts firm, Kelly Brothers, of Haverhill.

The building was supposed to be finished by July 1, 1898, but it was delayed until early 1902, “partially due to litigation with the architect over fees,” Shettleworth and Beard wrote.

Apparently the builder changed, because in William Abbott Smith’s chapter in Whittemore’s history the builder is Horace Purinton and Company and its spokesman referred to construction contracts signed July 12, 1901. The June 13, 1890, issue of the Waterville Mail, found on line, has a front-page ad for Horace Purinton & Co., contractors and builders specializing in brickwork and stonework, with headquarters in Waterville and brickyards in Waterville, Winslow and Augusta.

The 1975 application for historic recognition calls the building’s architectural style Colonial Revival. The basement and lower floor are stone, the two upper stories “brick with wood and stone trim.” The front features arched doorways and windows, Doric columns and decorative brick features and is topped by “an elaborate wooden cornice composed of a dentil molding, a series of modillions and an ornamental crest at the center bearing the inscription ‘City Hall.'”

Smith quoted from Horace Purinton’s remarks at the June 23, 1902, dedication of the new city hall. Purinton told his audience that material for the building came from as far away as Michigan and Indiana, with two exceptions. Some of the wood was logged and milled in Maine; and “The material for the brick was in its natural state in the clay banks within our borders.” (From the context, Purinton probably meant the borders of Maine, not of Waterville.)

The building’s interior is in two sections, Shettleworth and Beard wrote. City offices occupy the first two floors, with a main entrance on the south (Castonguay Square) side and another entrance on the east (Front Street) side. The upper part of the building is the large auditorium, originally called the “Assembly Rooms.”

The applicants described the auditorium in 1975 as still looking much as it did in 1902. They wrote that “The balcony and proscenium arch are ornamented with elaborate Baroque style plasterwork,” and the “original painted curtain bearing a large scenic landscape” was still there.

The first event in the Opera House was a dairymen’s exhibition, Shettleworth and Beard found – they gave no date. Later it hosted amateur shows and touring acting companies. Well-known artists who performed there included Australian actress Judith Anderson, American contralto Marion Anderson, singer and actor Rudy Vallee and cowboy actor Tom Mix, whose horse was “hauled up the outside of the building” to join him on stage.

After World War II, movies displaced live shows and the auditorium served as a movie theater. Beginning in 1960, Shettleworth and Beard found the venue resumed live productions – “plays, musicals, and recitals.”

“This kind of activity carried on in a 1900 theatre in a relatively small city is extremely unusual in this day and age,” they commented.

* * * * * *

Alas, your writer has, as so often happens, run out of space before she ran out of information. She hopes readers will find this description of a small part of Waterville’s history interesting enough to look for continuations in following weeks.

Main sources

Corbett, Matthew, and Scott Hanson, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Waterville Main Street Historic District, Aug. 28, 2012, supplied by the Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

Plocher, Stephen, Colby College Class of 2007, A Short History of Waterville, Maine, Found on the web at Waterville-maine.gov.

Shettleworth, Earle G., Jr., and Frank A Beard, National Register of Historic Places inventory – Nomination Form, Waterville Opera House and City Hall, October 1975.

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous.