Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Diary-keeping, Ballard & Bryant

by Mary Grow

Temporarily distracted from the Kennebec Valley, your writer recently read Richard Beeman’s Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution (2009).

Beeman described the 1787 convention in Philadelphia at which men from 12 of the 13 original states (Rhode Island refused to play) wrote what became the Constitution of the United States, succeeding the 1777 Articles of Confederation.

After four months of discussion and debate, on Saturday, Sept. 15, 1787, the delegates agreed on a document. They then went to their various lodging places to relax for the rest of the weekend.

The man who got no weekend off, Beeman wrote, was Jacob Shallus, the Pennsylvania legislature’s assistant clerk. He was directed to make a copy of the final document, to be ready for signing Monday.

Wikipedia and other sources say the Constitution was on four sheets of parchment, “made from treated animal skins (either calf, goat, or sheep).”

Shallus almost certainly used goose quill pens. The primary feathers – the first five flight feathers – from a goose (or swan) make the best pens, websites say. The point is shaped with a sharp knife, and the hollow shaft acts as an ink reservoir.

Wikipedia says the brownish-black or purplish-black ink Shallus used would have been made from “iron filings in oak gall.” (Galls are abnormal tissue growths on plants or animals; an oak gall, or oak apple, is caused by chemicals injected by wasp larvae.) The ink was a mix of fermented fluid from galls, known as tannic acid, and iron salts, with gum Arabic or some other binder added.

Wikipedia says this oak gall ink (which had other names) was Europe’s standard ink from the fifth through the 19th centuries and was brought to America. It “remained in widespread use well into the 20th century, and is still sold today.” The web has ads for goose quill pens.

Jacob Shallus was the son of German immigrants, born in Pennsylvania about 1750 and a Revolutionary War veteran. Wikipedia does not say how he got his job with the Pennsylvania legislature or how long he had been there when he was assigned to make the final copy of the Constitution. He died April 18, 1796.

Of course, the delegates had other documents in Philadelphia in 1787, like drafts of the Constitution with notes, and many wrote lots of letters (though, Beeman stressed, no one violated the rule of secrecy about the convention proceedings).

Your writer thought of the diary-writers in the much less civilized Kennebec Valley not many years after the Philadelphia convention. Martha Ballard, in Hallowell, and William Bryant, in Fairfield, are two your writer has already introduced in previous articles.

How did they find the materials – and the time, and the light – to do what they did? Records give only scant answers to such questions about daily life.

* * * * * *

According to Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s introduction to A Midwife’s Tale, an edited version of Martha Ballard’s diary, its predecessors were “two workaday forms of record-keeping, the daybook and the interleaved almanac.”

A typical daybook would be kept by a man engaged in commerce, who would record economic data and maybe add notes about his family or his job. Printed almanacs in the 18th century had blank pages on which owners could add information – Ulrich suggested “gardening, visits to and from neighbors, or public occurrences.”

Wikipedia says almanacs were popular in the American colonies, “offering a mixture of seasonal weather forecasts, practical household hints, puzzles, and other amusements.” Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack (1732-1758) was among the best known.

* * * * * *

Martha (Moore) Ballard (February 1735-May 1812) began her diary on Jan. 1, 1785, Ulrich wrote, and continued it for 9,965 days, over 27 years. The last entry was written May 7, 1812, about three weeks before Ballard died, Ulrich said.

For the – contested – date of Ballard’s death, she cited another local diarist, Henry Sewall (1752-1845), who wrote that Ballard’s funeral was on May 31. (Henry Sewall was profiled in the March 2 and March 9, 2023, articles in this series.)

By the beginning of 1785, Martha, her husband Ephraim (profiled in the Feb. 16, 2023, article in this series) and their children had been living on the Kennebec since October 1777, and she had been delivering babies there since 1778.

Ulrich’s book includes a photograph of two pages of Ballard’s diary, April 7 through 23, 1789. At the top of each page, starting in 1789, Ballard wrote the month and year. She ruled off a narrow left-hand margin for the date and for birth records. From 1788, she summarized the day’s events in a wider right-hand margin, often starting with the word “at” and naming the house where she visited or attended a birth, or a public event (or sometimes writing “at home”).

Horizontal lines separate the days. Two entries Ulrich showed are only two words each; others have up to 10 lines. An entry sometimes begins with a few words on the day’s weather.

Ballard’s handwriting was cursive, not printing. Her spelling and punctuation do not conform to modern standards; spelling is often phonetic and not always consistent.

But, Ulrich pointed out, in the 1780s few backwoods women could write at all. She found one document signed by Ballard’s grandmother, Hannah Learned; but Ballard’s mother, Dorothy Moore, couldn’t even write her name.

Some of the men in the family were educated, Ulrich found, including Ballard’s brother, a Harvard graduate. Ulrich surmised that Ulrich had received some basic education in her home town, Oxford, Massachusetts.

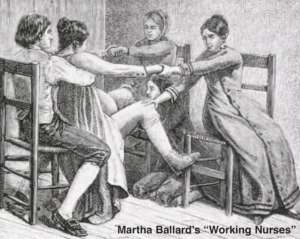

Ulrich observed that the diary contained information on a wide variety of subjects, from routines of daily life to medical practices to public events. Birth records included the family name, the baby’s sex, whether Ballard collected her fee and often other details.

Information with the online replica of the diary (see below) says Martha usually wrote at home after the rest of her family were in bed, quoting a 1797 comment as evidence. This source describes the diaries as hand-sewn booklets, small enough so Martha could put them in a bag or pocket.

Ulrich said the midwife sometimes carried diary pages with her on her medical errands, leaving the reader to imagine Ballard sitting by a fire in someone’s cabin or house writing, while waiting for sounds of progress from the expectant mother and her companions in the next room.

The on-line informant says Ballard wrote with a quill pen (probably taking the quills from her own geese) and home-made ink. Evidence for the ink is a quotation from Sept. 6, 1789; Martha wrote that she “made” the ink she was using that day from “Cake ink which mr Ballard Sent to Boston for.”

In the epilogue to A Midwife’s Tale, Ulrich wrote that after Ballard’s death, her diary descended through the family as a collection of loose pages. In 1884, a great-great-granddaughter named Mary Forrester Hobart, a medical school graduate, inherited it.

A cousin of Hobart’s arranged the pages in order and created a two-volume book. In 1930, Hobart donated it to the Maine State Library.

Meanwhile, Augusta historian Charles Elventon Nash had excerpted many entries to include in his history of Augusta. He finished the first volume just before his death in February 1904.

Nash’s manuscript was stored, unpublished, until the fall of 1958, when Nash’s son’s widow asked if the state library would take it. Edith L. Hary, then the state librarian, urged acceptance.

As she explained in the foreword to Nash’s history, finally published in 1961, the manuscript was moved to the library, as her responsibility. She found it worth publishing not only for Nash’s sake, but because it included so much of the unpublished Ballard diary.

As of the end of 2023, there is a replica of the diary available on line, credited to Robert R. and Cynthia MacAlman McCausland (search for Martha Ballard’s diary). Accompanying information says there is a hardbound copy available through Picton Press; when your writer looked up Picton Press, she found the sad messages that the press is permanently closed and for sale.

* * * * * *

William Bryant (Jan. 5, 1781 – June 15, 1867) is identified in the Fairfield bicentennial history as “the diarist.” The Fairfield Historical Society’s collection of documents includes typed transcriptions from his diary, which he evidently started in 1822 and kept at least sporadically until Feb. 6, 1867, when he made his last entry.

The historical society files include related documents, like newspaper clippings about commemorations of his birthday. Nothing casts any light on materials he used to write the diary, and several historical society members could provide no information.

Bryant served on the “USS Constitution” on her maiden voyage in 1797, when he would have been 16 years old. One story is that he was a cabin boy, whose duties would have included waiting on officers and crew and perhaps helping the cook. Another version is that he was a powder monkey, one who brought gunpowder from the hold to the cannon during battles.

He was almost certainly born Jan. 5, 1781, because in his diary he wrote that he was 60 years old on Jan. 5, 1861. However, the genealogy WikiTree, found on line, gives his birthdate as Jan. 5, 1783, in Sandwich, Massachusetts Bay.

Bryant’s diary says his father was Matt Bryant (September 1749–April 1810) and his mother was Abigail, born in Sandwich July 1755 and died April 20, 1842; he recorded her death in his diary. WikiTree gives Abigail’s maiden name as Nye and her dates as July 27, 1755 to Sept. 22, 1841, the latter undoubtedly an error. The same source called his father Moto or Motto Bryant or Briant.

William Bryant married Lydia Haley. He wrote in his diary that their wedding was April 4, 1805, in Wickford Village, part of North Kingston, Rhode Island.

On Jan. 31, 1854, he wrote that Lydia was 75 years old, which would make her birthday Jan. 31, 1779. WikiTree says she was born Jan. 31, 1781, in Thompson, Connecticut, and died May 22, 1858, in Fairfield, Maine.

Bryant wrote that Lydia fell ill in May 1858 and died peacefully at 8 p.m., Saturday, May 22.

WikiTree names two Bryant daughters, Mary E. (Bryant) Connor (1810-1897), mother of Maine Governor Seldon Connor, and Harriet Hinds (Bryant) Drew. The same source lists, from the 1850 census of Benton, Maine, William and Lydia, each age 69, and in the same household 26-year-old Samuel H.

Another source says the Bryants had five children between 1810 and 1823. The Fairfield bicentennial history says daughter Susan became Mrs. Nahum Totman.

Information from the historical society’s collection says Bryant was in Waterville, Maine, in 1809, in Rhode Island in 1813 and in Fairfield, working as a hatter, by 1817. In a Nov. 19, 1827, diary entry, he wrote that “Bugden” a clockmaker from Augusta, visited and apparently brought him one or more clocks, because “I paid him $14 in hats.”

Bryant was elected a representative to the Massachusetts General Court in 1819 and 1820, and later served two terms in the Maine legislature.

In November 1831 he bought a farm at Nye’s Corner, and moved there, he wrote, on June 4, 1832. Many diary entries discuss farming and weather.

Apparently Bryant skipped the March 1838 town meeting, because he wrote that he was informed he had been elected to no local office “except the Committee on Accounts.”

This news hurt. He wrote that up to then, he had been 10 years a selectman (the bicentennial history says he served a total of 19 terms as a selectman) and overseer of the poor and 11 years an assessor; and he was further “informed that it was generally agreed that I performed the duties of the offices faithfully and correct”; and that he did not “seek office for the honor.”

Main sources

Beeman, Richard, Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution (2009).

Fairfield Historical Society, for Bryant diary.

Fairfield Historical Society Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988).

Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher, A Midwife’s Tale The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812 1990.

Websites, miscellaneous.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!