REVIEW POTPOURRI – Music: The Penguins; Writer: Alfred Kazin; TV Show: Dragnet

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates

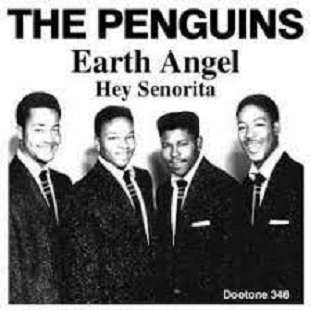

The Penguins

I own a ten inch 78 (Dootone 348) containing two songs performed by the doo wop vocal group, the Penguins – Hey Senorita and Earth Angel. It was released in late 1954 and, in early 1955 in an ironic twist of commercial fate, side one’s Senorita, even though pleasant enough, would be ignored by disc jockeys in favor of Earth Angel soaring to #1 on the rhythm and blues charts for three weeks with 4 million copies sold by 1966 and very musically deserving of its success.

At the beginning, the group consisted of the following singers:

Lead tenor Cleveland Duncan (1935-2012), Curtis Williamson (1934-1979), Dexter Tisby (1935-2019), Bruce Tate (1937-1973), vocalist Williams, Gaynel Hodge and the late, great singer Jessie Belvin, who died very young, shared credit in the writing of Earth Angel.

In 1958, the group signed a contract with Mercury Records where the musically similar Platters would score even greater success while the Penguins own sales were already waning.

In 1955, an all white group, the Crewcuts, recorded their own version for Mercury, scored an even greater success on the pop charts and began their own rise to fame.

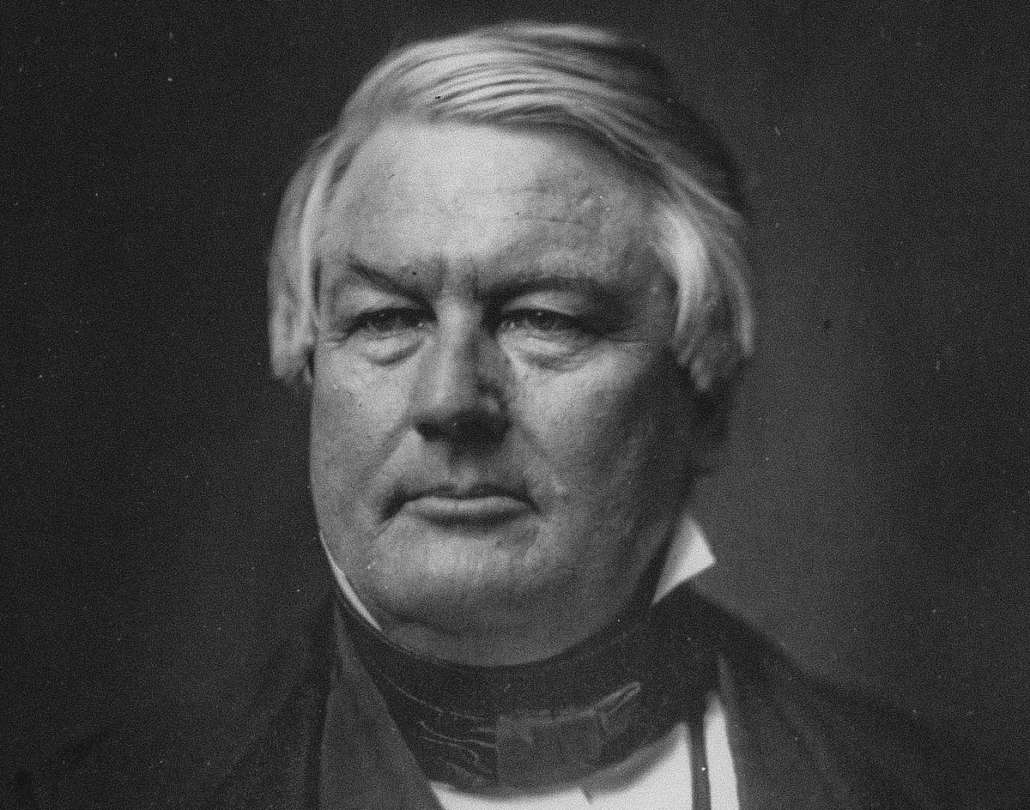

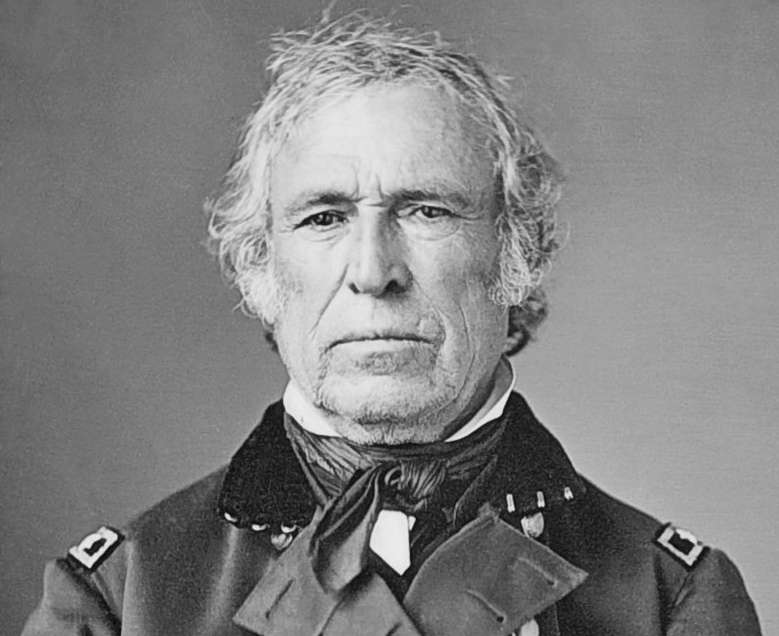

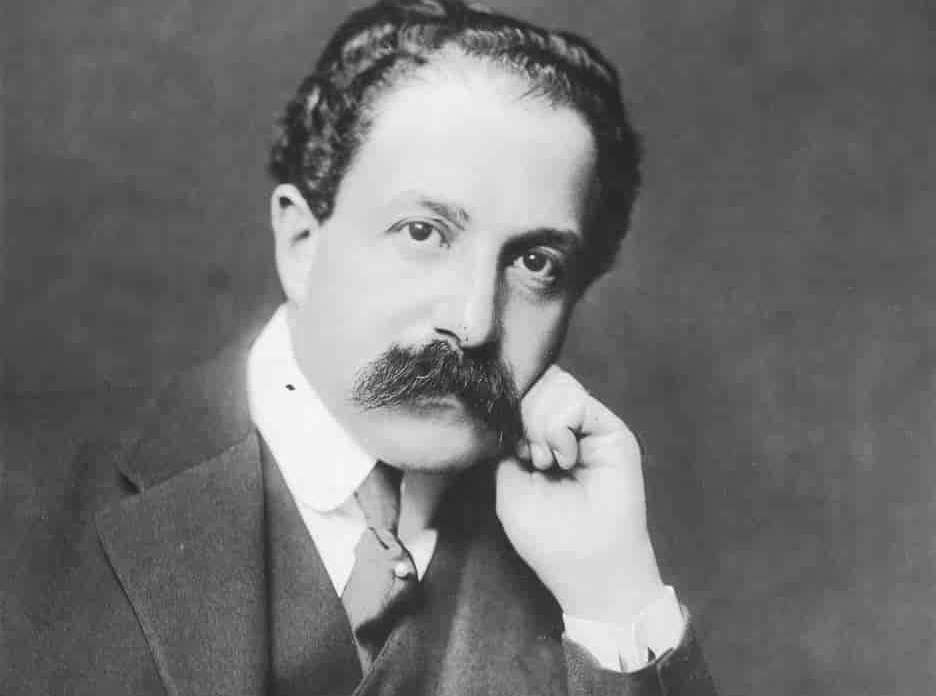

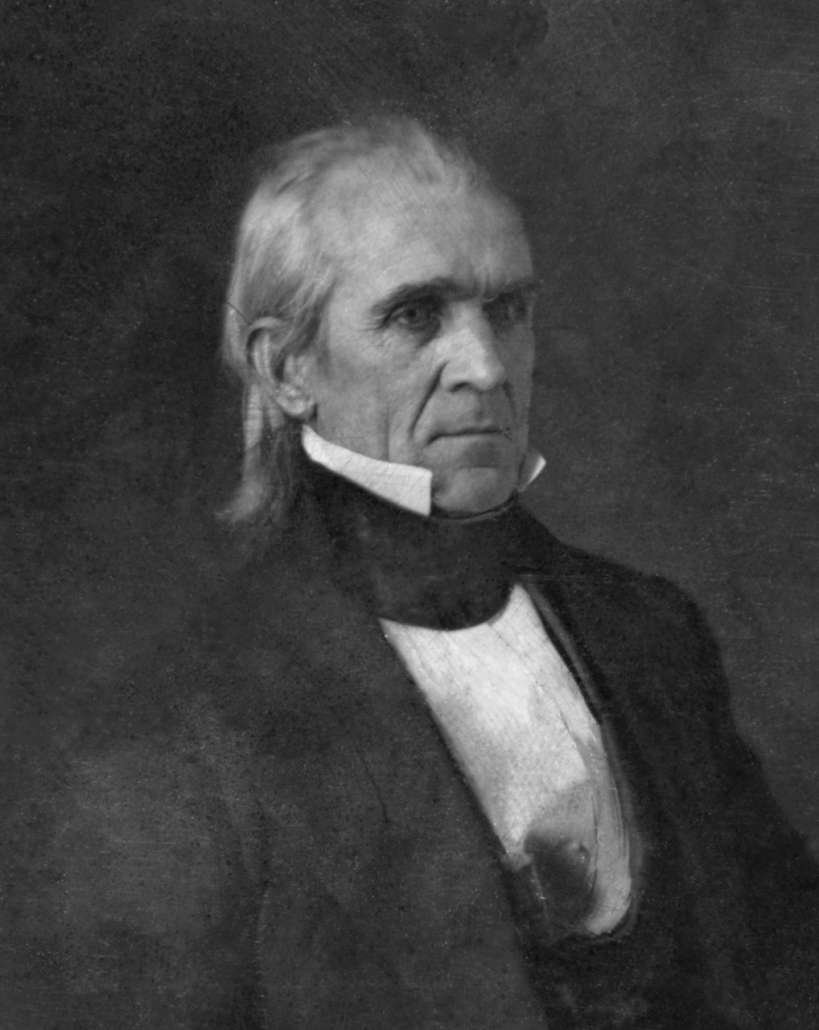

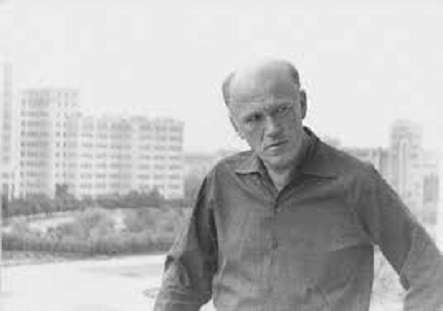

Alfred Kazin

Alfred Kazin (1915-1998) stated in his Journals on March 22, 1960, a pre-requisite for truly worthwhile writing:

“Without some kind of innocence, no writing is possible. One must give oneself to the world, uncomplainingly, no matter what….”

Interestingly, he complained constantly in these Journals, but still remains one of a handful of writers, most of whose books I have read. One gentleman who knew him commented to me back in the 1980s that “Alfred is not a nice man.”

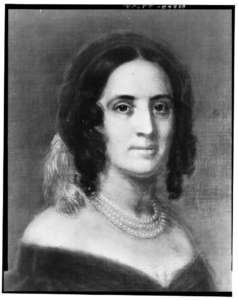

On the other hand, Southern writer Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964) invited a friend to lunch at her Milledgeville, Georgia, farmhouse and informed her that “Alfred Kazin would be joining them and that he was a sweetie.”

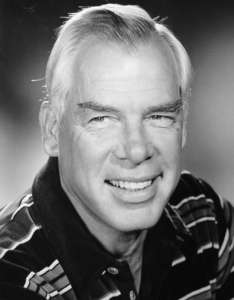

Dragnet

One of the most underrated examples of early 1950s film noir suspense black and white entertainment are the episodes of Dragnet. One had Lee Marvin portraying a serial killer who’s also a vegetarian and takes Jack Webb’s Joe Friday and his partner to dinner at a then-existing restaurant in Los Angeles.

However Marvin’s character, portrayed with precision-honed calm and based on an actual individual, would still be sentenced to the gas chamber which was a frequent punishment for murderers in the California of that decade.