TECH TALK: My deep, dark journey into political gambling

ERIC’S TECH TALK

ERIC’S TECH TALK

by Eric W. Austin

I opened the door and stepped hesitantly into the dimly lit room. Curtains covered all the windows. The only light came from a half-dozen computer screens glowing menacingly in the darkness. A scary-looking German Shepherd slumped in one corner. She growled low in her throat as I came in, and then went back to scratching at imaginary fleas. She had seen it all before: just another poor sucker thinking it was possible to predict the future.

But this wasn’t some hole-in-the-wall gambling den in a seedy part of Augusta. It was my office at my house here in China, Maine. I sat down at my desk and pulled up the website PredictIt.org. Would I be up or down today?

source: predictit.org

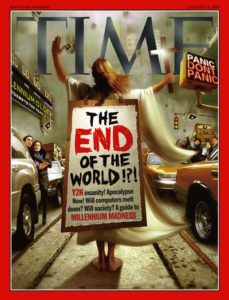

PredictIt is a different kind of gambling website. Instead of betting on sports events or dog races, you bet on events happening in politics. For example, the Friday before the recent government shutdown, I pulled out of the “Will the government be shutdown on January 22?” market after quadrupling my initial investment. I got into the market two weeks earlier when I thought shares for ‘Yes’ were severely undervalued at only 16¢ a share. When I exited the market on Friday, my 20 shares were valued at 69¢ each. I should have held the line, but still not a bad return on investment in only two weeks. When in doubt, bet on the incompetence of the American Congress.

Called the “stock market for politics,” PredictIt is an experimental political gambling website created by Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. They work in partnership with more than 50 universities across the world, including the American colleges of Harvard, Duke and Yale.

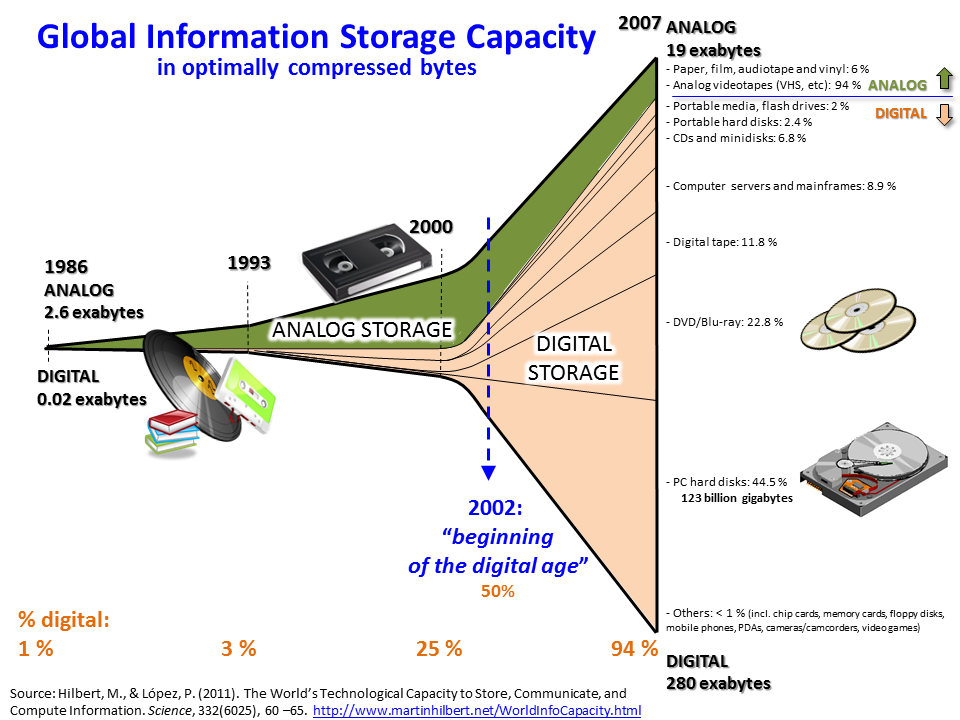

Why would a bunch of academics be interested in political gambling? They’re studying a psychological phenomenon called “the wisdom of the crowd.” This is a theory that postulates that a prediction derived from averaging the opinions of a large group of diverse individuals is often better than the prediction from a single expert.

The way it works on PredictIt is pretty simple. Political questions are posed which have a binary response, usually ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. Shares in either option cost between 1¢ and 100¢ (or $1). The value of shares is determined by the supply and demand of each market. In other words, if a lot of people are buying shares in the ‘Yes’ option, those shares will increase in value, and ‘No’ shares will decrease.

This set up allows one to quickly look at a share price and know how likely that particular prediction is of coming true. Will Trump be impeached in his first term? Since shares are currently at 37¢, that means the market thinks there’s a 37 percent chance of that happening. I own 15 ‘Yes’ shares in this market. Shares have increased by 4¢ (or 4 percent) since I entered the market several months ago (from 33¢ to 37¢), so my initial investment of $4.90 has increased by 65¢ to $5.55 as of today.

If you can think of a question related to politics, there’s likely a market for it on PredictIt. Will North Korea compete in the 2018 Winter Olympics? Currently likely at 94 percent. Who will be the 2020 Democratic nominee for president? At the moment, Bernie Sanders and Kamala Harris hold the top spots. How many senate seats will the GOP hold after the mid-term elections? “49 or fewer” is the most likely answer according to investors on PredictIt.

What are the chances that events over the next year will change things up? There’s no market for that question on PredictIt, but I’d say it’s at least 100 percent. Of course, that’s exactly what makes the game so exciting!

I first entered the world of political gambling back in May. I’d become a bit of a news junkie during the 2016 election (Donald Trump is the news equivalent of heroin), and was looking for something to give meaning to the endless hours I spent following the machinations in Washington. Initially, I started with just $20. Later, I added another $25 for a total account investment of $45. I lost $8 on a couple of bets early on, and have spent the past six months trying to make up for the losses. This government shutdown drama put me back on top. According to my trade history, after more than 169 bets and minus any trading fees, I’m currently up by $9.96.

Okay, so the IRS is unlikely to come knocking on my door when I don’t report it on my taxes in April. Still, it feels good to be back in the black.

Eric Austin is a writer, technical consultant, and news junkie living in China, Maine. He can be contacted by email at ericwaustin@gmail.com.

For small papers like The Town Line, which offers the paper for free and receives little income from subscriptions, this is an especially hard blow: more people are reading the paper, and there’s a great demand for content, but there is also less income from advertising to cover operating costs.

For small papers like The Town Line, which offers the paper for free and receives little income from subscriptions, this is an especially hard blow: more people are reading the paper, and there’s a great demand for content, but there is also less income from advertising to cover operating costs.

Unlike your personal computer, a driverless car is a thinking machine. It must be capable of making moment-to-moment decisions that could have real life-or-death consequences.

Unlike your personal computer, a driverless car is a thinking machine. It must be capable of making moment-to-moment decisions that could have real life-or-death consequences.