Up and Down the Kennebec Valley: Revolution effects Vassalboro & Winslow

by Mary Grow

A 1770s map of Kennebec River towns upriver from Augusta would look quite different from a 2025 map, or even an 1870s map. Currently, Augusta is the only area town with territory on both banks of the river (linked by two bridges).

Upriver on the west bank, one goes from Augusta north into Sidney, then Waterville and then Fairfield. On the east bank, the next town north of Augusta is Vassalboro, then Winslow, then Benton.

In the 1770s, Vassalboro included Sidney (the two separated effective Jan. 30, 1792) and Winslow included Waterville (which became a separate town on June 23, 1802). Fairfield, then a plantation (it became a town on June 18, 1788) was on the west bank only, as it is now. Opposite it was a piece of what became Clinton when the town was incorporated in 1795; Benton became a separate town in 1842.

These future towns along the river all had small populations in 1775. As previous articles have discussed, Fort Halifax, in Winslow, was built in 1754, and the area was inhabited thereafter. Much of the rest of the river valley attracted at least scattered settlers, especially after the Kennebec Proprietors had a survey finished and lots laid out by 1761.

Hallowell (including Augusta), Vassalboro (including Sidney) and Winslow (including Waterville) had large enough populations to justify their incorporation as towns on April 26, 1771.

The 1988 Fairfield bicentennial history says the first recorded log cabin was built on the river, a couple miles north of the present downtown, in 1771; in 1774, the area had enough families to be organized as Fairfield Plantation.

In Clinton, according to Carleton Edward Fisher’s 1970 town history (quoted in the town’s comprehensive plan on line), the first settler arrived after 1761, but before the Kennebec Purchase Company (aka Kennebec Proprietors etc.) began offering lots in 1763. Other sources propose other dates.

* * * * * *

Henry Kingsbury commented in his chapter on Vassalboro in his 1892 Kennebec County history that “The records of the town from 1771 to the present are in four leather-bound books, well preserved and beautifully written.”

Alma Pierce Robbins’ 1971 Vassalboro history includes numerous excerpts from these records, with miscellaneous references to the Revolution. She described residents as “somewhat lukewarm” and said they “did their share in a dilatory manner”; but “There were many who did join their fellow countrymen in the cause for ‘Liberty.'”

The earliest vote she cited was from an otherwise undated 1773 town meeting (probably in the spring): “to be exempt from sending a representative to the [Massachusetts] General Court, and to join Boston concerning the Liberty of the Colony.”

Another meeting was called in September 1773 to hear information from Boston and see if voters would create a Committee of Correspondence. (Committees of Correspondence were the local revolutionary organizations that shared information and coordinated efforts throughout the colonies.) Whether Vassalboro had one, Robbins did not say.

Town voters did choose a “Captain of the Town for the Emergency of the times” at a Jan. 16, 1775, meeting. The first captain was Dennis Getchell (see box), assisted by two lieutenants and an ensign.

At that same meeting, Robbins wrote, voters approved a long resolve to be sent to Massachusetts authorities. It referred to the Continental and Provincial Congresses’ “almost unexplained Love for the Liberties of their Country” and agreed to abide by current and future Congressional recommendations.

Town Clerk Samuel Devens added a promise to “tender their [the town’s] assistance whenever required.” A prominent resident named Remington Hobby carried the message to Massachusetts. (Hobby was mentioned in the Aug. 21 article in this series as Vassalboro’s delegate to a 1774 provincial congress.)

Robbins wrote that by July 1776, Vassalboro’s town meetings were called “in the name of the Governor and People of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay,” replacing the British monarch. (Hallowell made a similar change in January 1775, as reported in the Aug. 21 history article.)

During the war years, Tories were as unpopular in Vassalboro as elsewhere. Robbins mentioned instances of their being mobbed or arrested.

Her chapter on wars includes no details on Vassalboro soldiers in the Revolutionary army. In an earlier article in this series (see the Feb. 3, 2022, issue of The Town Line), your writer mentioned Amos Childs, Dennis Getchell and Charles B. Webber. On-line resources list land grant applications for John Bailey, Joab Bragg and Benjamin Collins, or their widows.

* * * * * *

The first Europeans in what is now Winslow were British traders. Kingsbury cited a 1719 survey that included reference to a man named Lawson who had a trading house at the Native village of Ticonic in September 1653.

By 1675, the firm of Clark & Lake owned this business, and Richard Hammond had a second trading post at Ticonic, Kingsbury said. Neither man survived the series of wars that began that year, as French-supported Natives tried to repel settlers coming into their territory from the coast.

As part of the settlers’ advance, the Plymouth Company (aka the Kennebec Proprietors and other titles) and the Massachusetts government built Fort Halifax (and its southern neighbor, Fort Western, in Augusta) in 1754. By April 26, 1771, the town by and across the Kennebec from the fort (still intact, though demilitarized after the French and Indian Wars ended in 1763) had enough people to be incorporated as the Town of Winslow.

Kingsbury had only one comment on the Revolution in his chapter on the town. He wrote: “In 1776 the people manifested their patriotism by appointing Timothy Heald, John Tozer and Zimri Haywood a committee of correspondence.”

Rev. Edwin Carey Whittemore, in his 1902 Waterville history, listed these three men as the first Committee of Safety (later, the Committee of Correspondence, Inspection and Safety), and eight more — Ezekiel Pattee, Robert Crosby, Manuel Smith, Ephraim Osborne, Nathaniel Low, Hezekiah Stratton, William Richardson and Benjamin Runnals – as members of Winslow’s Committees of Correspondence through the war.

(Heald, Tozer and Haywood also served the town as selectman, town clerk and/or town treasurer. Ezekiel Pattee served 19 years as a selectman, three one-year stints as town clerk and, Kingsbury said, as town treasurer from 1771 to 1794, except for 1781, when Haywood had the job. In the 1780s, Haywood and Pattee each represented Winslow in the Massachusetts legislature, Whittemore said.)

In Winslow, Whittemore said, the first town meeting to be called in the name of Massachusetts Bay was on July 8, 1776.

Winslow had no money to meet the requirement to buy ammunition, so Whittemore wrote that voters borrowed shingles and clapboards from residents, including Pattee, Tozer and Heald, sold them and bought ammunition with the proceeds.

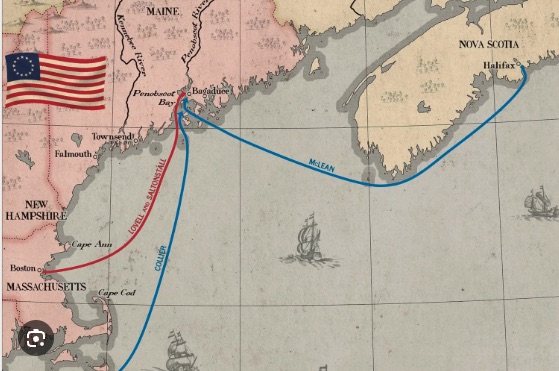

He gave no date for that transaction, nor for the decision to send three men “up the river to see whether any British force was approaching.”

As in other towns, Whittemore wrote that Winslow had trouble finding men to serve in the army and meeting government requisitions of clothing and beef.

General Isaac Sparrow Bangs did a great deal of research for his chapter on the military in the Waterville history, apologizing for the scant results and regretting that records were not compiled while Revolutionary veterans and their families were still alive. He came up with a list of more than two dozen service men’s names (a few might be duplicates), with varying amounts of information about each.

The first man on the list is Captain Dean Bangs (May 31, 1756 – Dec. 6, 1845), the writer’s grandfather. Still living on Cape Cod when the war started, he was a privateer for a year before serving in the army for two years. Dean Bangs moved to Sidney in 1802 and died there; his grandson called Waterville “his mercantile home,” from where he raised an artillery company during the War of 1812.

A private named John Cool (died Oct. 5, 1845, aged 89 years and six months) served from March 12, 1777 to March 12, 1780. Bangs wrote that on May 26, 1835, Cool wrote (on a pension or similar application?) that he was 78 years old and had been a Winslow/Waterville resident for 70 years. After his death, Bangs said, Cool Street, along the west bank of the Messalonskee Stream, was named after him.

Sampson Freeman served as a private from Feb. 1, 1777, to Feb. 5, 1780, including wintering at Valley Forge from December 1777, to June 1778. He was a free Black man who enlisted from Salem, Massachusetts; moved from Peru, Maine, to Waterville in 1835; and died in Waterville in 1843.

(The Town Line’s May 5, 2022, history article has more information about Sampson Freeman.)

Salathiel Penny or Penney (1756 – Sept. 22, 1847) Bangs found listed several times. Enlisting from Wells on May 3, 1775, Penney served eight months; he re-enlisted Jan. 10, 1776, for another 10 months; and yet again Jan. 1, 1777. Bangs wrote that Penney was “present at the surrender of [British General John] Burgoyne” on Oct. 17, 1777, at Saratoga, New York.

In another chapter in Whittemore’s history, Aaron Appleton Plaisted names Penney among pre-1800 Waterville residents.

Dennis Getchell

On-line sources say Dennis Getchell was born in Berwick in 1723 and married Mary Holmes (no dates given) in Wiscasset, in September 1761; the couple had at least 11 children, FamilySearch says. It then confuses the issue by saying all but two were born in Berwick, including those born after the Getchells moved to Vassalboro.

This source says Dennis, Jr., was born in 1771, in Clinton; or, a different source says, in Vassalboro. Daughters Anstrus and Lydia were reportedly both born in 1775, Anstrus in Berwick and Lydia in Vassalboro.

WikiTree mentions Getchell’s experience in the British military before he bought land in Vassalboro’s Riverside area in 1769 and 1770. At Vassalboro’s first town meeting, on April 26, 1771, he was elected first selectman.

WikiTree says: “On July 23, 1776, he was commissioned captain of the 5th company, 2nd Lincoln County regiment of Massachusetts militia. He and his company of 50 men served at Riverton, R. I., in 1777.”

Kingsbury agreed that Getchell was elected a Vassalboro selectman in 1771, and added that he served for eight years. In 1775, he was town meeting moderator. Another source says in 1786, he represented the town in the Massachusetts legislature.

Getchell died Aug. 23, 1791, according to a reader’s comment on WikiTree citing Martha Ballard’s diary; or early in 1792 (per WikiTree, which says his Aug. 2, 1790, will was probated Jan. 6, 1792).

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971)

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, (1902)

Websites, miscellaneous.