Up and Down the Kennebec Valley: Courts – Part 4

by Mary Grow

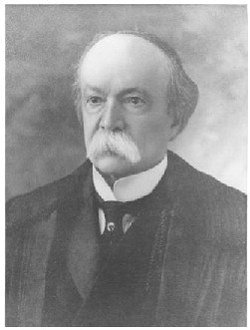

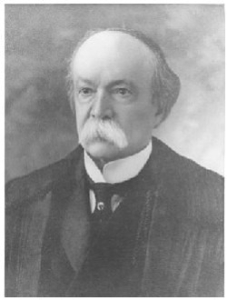

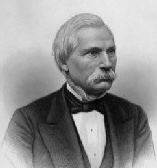

William Penn Whitehouse has been mentioned in each of the three articles about Maine courts so far in this subseries; it’s time he got a page of his own (after a digression).

The first mention, March 27, identified Whitehouse as the author of the chapter on the history of Maine courts in Henry Kingsbury’s 1892 Kennebec County history.

By then, Whitehouse was 50. He was married, and he and his wife had had three children and lost two of them. After a dozen years as a Kennebec County judge, in 1892 Whitehouse was in his second year as an associate justice on the state supreme court. He and his wife were living in Augusta, in an 1851 Greek Revival house he bought in 1869.

That this distinguished and busy man made time to research and write a chapter for Henry Kingsbury is a tribute to both of them.

Your writer has failed to find biographical information on Henry Kingsbury or his co-editor, Simeon L. Deyo. On-line booksellers list Deyo as editor of History of Barnstable County, Massachusetts, 1620-1637-1686-1890, and suggest it was originally published in 1890.

The book that Kingsbury and Deyo put together has about 1,300 pages (some page numbers are duplicated and one triplicated, 564, 564b and 564d [before and after 564b are unnumbered full-page illustrations]). The pages measure 7.5 by 10.5 inches; the print is fairly small. There are more than 200 illustrations, many full-page.

A few chapters are credited to Kingsbury; more than a dozen to other authors, like Whitehouse; none to Deyo. Twenty-five of the 47 chapters have no author’s name.

In his December 1892 introduction, Kingsbury (the only signatory, without Deyo) thanks “the twenty writers whose names these chapters bear” and “more than twenty hundred” people with whom “we” (including Deyo?) corresponded or spoke.

* * * * * *

William Penn Whitehouse was born April 9, 1842 (FamilySearch and other sources), or April 9, 1843 (Find a Grave), in Vassalboro. His parents, also Vassalboro natives (per FamilySearch) were John Roberts Whitehouse (1807 – April 16, 1887) and Hannah B. (Percival) Whitehouse (1808 -Nov. 29, 1876).

FamilySearch says John and Hannah were married “about 22 July 1827.” William was the youngest of their four sons and three daughters born between 1830 and 1842. Find a Grave lists the three older brothers but only one older sister.

The Find a Grave website has a long excerpt credited to Louis Hatch, author of a 1919 Maine history, but not from that book. Hatch said the Whitehouse family in America “has produced eminent churchmen, distinguished jurists and men of affairs and philanthropists that have had a national reputation, but none among them have more worthily borne the name and upheld the tradition than has William Penn Whitehouse….”

Writing when Whitehouse was in his late 70s, Hatch continued: “A man of the widest and most generous culture, his legal acumen and his fair mindedness together with a sense of duty which has a certain Roman quality have eminently fitted him for his lifework of the law. He unites a wide outlook and a scholarly culture with a keen and ready mind that has never lost its cutting edge. His gracious and urbane manners appear the natural fruit, as indeed they are, of his character and attainments.”

Hatch said Whitehouse began China Academy’s college preparatory course in February 1858, when he was 16 and still working on the family farm in Vassalboro, and learned so fast that he entered Colby College in September 1858. (China Academy was in China Village; chartered in 1818 by the Massachusetts legislature, it transformed into a free high school in 1880.)

James Bradbury, in his chapter on the Kennebec bar in Kingsbury’s history, agreed that Whitehouse went from the district school to “the China high school,” but wrote that the “scantiness of the knowledge there acquired” led him to enroll in Waterville Academy in February 1859 and enter Colby (for which Waterville Academy was a preparatory school) in September 1859.

Both sources agree Whitehouse graduated with honors in Colby’s Class of 1863 (making the 1859 entrance date more likely), and earned a master’s degree in 1866. Hatch said he taught for a while; both wrote that in 1863-64 he was principal of Vassalboro Academy (the girls’ school at Getchell’s Corner founded in 1837).

Deciding on the legal profession, Whitehouse studied law with area attorneys and in October (Hatch) or December (Bradbury) 1865 was admitted to the Kennebec Bar. He practiced briefly with other lawyers before opening his own practice in Augusta.

Hatch wrote that he was Augusta city solicitor for four years (Bradbury said he was elected in 1868) and Kennebec County attorney for seven years (or more, Bradbury said, appointed after his predecessor died and then twice elected because of his “efficient and impartial administration”).

In 1878, Bradbury wrote, Kennebec County Superior Court was created “as a county court auxiliary to the supreme judicial court” and Whitehouse was appointed the judge, a position he held until his 1890 appointment to the state Supreme Court.

Bradbury, like Hatch, had high praise for Whitehouse. Referring to his years as a lawyer, he wrote:

“Reared on a farm, and possessing the plain, practical directness which such a life inculcates, combined with the discriminating tastes of the scholar, and the keen analytical methods of a mind trained to an exacting profession, Judge Whitehouse speedily won an enviable standing as a man and a lawyer, and became a prominent figure in the public life of his adopted city.”

Later, he commented that Whitehouse’s habit of “taking cognizance of both sides” of an issue at first discouraged clients seeking a lawyer’s support, but later brought friends, clients and professional success, and was an important qualification for his future judicial roles.

Community activities Hatch and Bradbury mentioned included chairing an 1873 commission considering a new “insane hospital,” and in 1875 and later advocating for abolishing the death penalty.

The Kennebec County court was known unofficially as “Judge Whitehouse’s court,” Bradbury said. He called it “a very useful and important branch of the state’s judiciary.”

He named only one of Whitehouse’s superior court decisions: “the celebrated Burns ‘original package’ case,” which he called “the corner stone upon which rests [in 1892] the entire fabric of prohibition in Maine.” (See box)

Gov. Edwin C. Burleigh appointed Whitehouse an associate justice on the state supreme court on April 15, 1890. Bradbury observed that Whitehouse’s “splendid record” on the Kennebec County court was “his best recommendation” for the new position.

Whitehouse was reappointed by three later governors, Llewellyn Powers, on April 24, 1897; John Fremont Hill, on April 5, 1904; and Frederick Plaisted, on April 13, 1911. Plaisted appointed him Chief Justice on July 26, 1911, after Lucilius Emery, from Ellsworth, resigned.

Historian Hatch was again elated, writing:

“A profound knowledge of the law, a ripe and scholarly culture and trenchant mind were in him associated with a balance and sanity of temperament and a judicial habit of weighing evidence in its minutest detail. No man who has occupied the Supreme bench of the State of Maine, rich as has been its history, has by character of [or?] attainments more nobly carried out its highest traditions.”

Whitehouse resigned the position on April 8, 1913. He was succeeded by Albert R. Savage, from Auburn, who held the post until his death in June 1917.

Hatch summed up Whitehouse’s tenure:

“A profound knowledge of the law, a ripe and scholarly culture and trenchant mind were in him associated with a balance and sanity of temperament and a judicial habit of weighing evidence in its minutest detail. No man who has occupied the Supreme bench of the State of Maine, rich as has been its history, has by character of [or?] attainments more nobly carried out its highest traditions.”

He said nothing about why Whitehouse resigned. Apparently not due to illness or disillusionment, however, because Hatch said he re-opened his law firm and as of 1919 “commands an important and distinguished practice.”

In addition to his work for the new Augusta insane hospital, Whitehouse was a bank trustee, Hatch said. His “services to the State and to the legal profession” were recognized by honorary doctorates from Colby in 1896 and from Bowdoin in 1912.

* * * * * *

In politics, Whitehouse was a Republican (Hatch and Bradbury); in religion, a Unitarian (Bradbury, though his father was a Quaker and his mother a Methodist).

On June 18 (FamilySearch) or June 24 (Find a Grave and Bradbury), 1869, Whitehouse married Evelyn Marie or Maria Treat, born in Frankfort on June 4, 1836. The couple had three children: Robert Treat, born March 27, 1870; William Penn, Jr., born May 12, 1873, and died June 5, 1874; and Minnie Drew, born Oct. 13, 1875, and died Jan. 10, 1877.

William Penn Whitehouse died Oct. 10 or Oct. 22, 1922, in the Augusta house he bought in 1869. His widow lived until 1925 (your writer found no exact death date).

William and Evelyn’s son who lived to adulthood, Robert Treat Whitehouse, married Florence Brooks in 1894 in Augusta, according to FamilySearch. They had at least three sons, whom they named William Penn Whitehouse (1895 – 1976), Robert Treat Whitehouse, Jr. (1897 – 1965) and Brooks Whitehouse (1904 -1969).

The sons were born in Portland, where Robert practiced law. He died there in 1924; his widow died in Portland on Jan. 23, 1945.

Augusta’s Forest Grove cemetery contains the graves of 32 people named Whitehouse, including, according to Find a Grave, William Penn and Evelyn; their son Robert Treat and daughter-in-law Florence; their children who died as infants, William Penn, Jr., and Minnie; and their grandsons William Penn II, Robert Treat, Jr., and Brooks.

William Penn’s parents, John Roberts and Hannah (Percival) Whitehouse, and his brother Oliver (1839 – Oct. 31, 1869) are buried in Vassalboro’s Whitehouse cemetery, on Whitehouse Road, a former section of Routes 202 and 3 in southeastern Vassalboro.

The Burns case

An on-line search for the Burns original package case led your writer to a 1911 legislative resolve in favor of an Augusta businessman named Michael Burns.

The resolve was to reimburse Burns $3,132.86 “for his expenses incurred in defense of prosecutions instituted against him, without warrant of law under the specific order of the governor, and for loss of property and injury to his business.”

The document explained that in 1887, Burns was selling “original, unbroken, imported packages of alcoholic liquors.” He was complying with federal law, and both state law and three Maine Supreme Court decisions said his business was legitimate (despite Maine being a famously “dry” state in those days).

The Kennebec County sheriff and county attorney, the municipal judge, the attorney general, “the legal profession and all well-informed citizens” knew that it was legal to sell alcohol in Maine in these “original, imported, unbroken packages.”

Nonetheless, in June, 1887, the governor issued a proclamation directing the attorney general and the Kennebec County attorney to prosecute Burns for illegal liquor sales. (In June 1887, Maine’s governor was a Republican named Joseph R. Bodwell; he was elected in 1886, took office Jan. 6, 1887, and died in office Dec. 15, 1887.)

Obeying the governor, the county attorney had the sheriff, a man named McFadden, seize 56 cases of rum and 13 cases of whiskey, with a market value of $483. (The Waterville centennial history says Charles McFadden, a Vassalboro native who moved to Waterville, held various official positions, including Kennebec County Sheriff from 1884 to 1888.)

Burns hired a lawyer, and his case dragged on for three years. On May 29, 1890, the law court (i.e., the state supreme court acting as a court of appeals) agreed that Burns’ business was legal. In its September 1890 term, the “presiding judge” (unnamed) of the Kennebec County Superior Court ordered the cases of liquor returned to Burns.

(Whitehouse having been appointed to the Maine Supreme Court in April of that year, Bradbury’s report of his involvement puzzled your writer.)

Meanwhile, however, the legislative resolve says, on Aug. 8, 1890, a federal law had redefined the packaged liquor as contraband in Maine, and it had been sold in Boston, at a $300 loss.

The legislative resolve listed a total of $1,299.94 in losses and expenses Burns had incurred. It then added $1,832.92 for 23 and a half years’ interest to order the $3,132.86 reimbursement (and mentioned other losses for which it could have required reimbursement, but didn’t).

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed. Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Websites, miscellaneous.