ERIC’S TECH TALK: Surviving the surveillance state

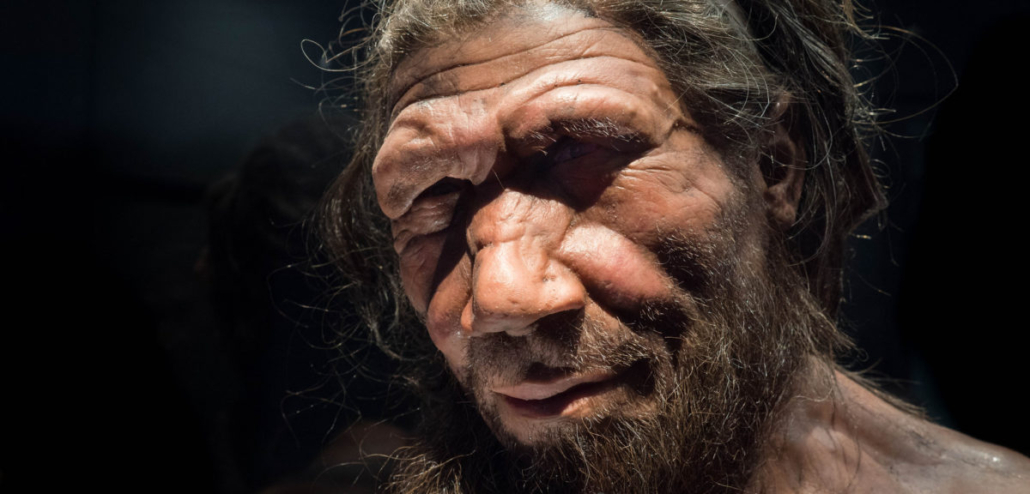

An artist’s rendering of a Neanderthal.

by Eric W. Austin

by Eric W. Austin

Let me present you with a crazy idea, and then let me show you why it’s not so crazy after all. In fact, it’s already becoming a reality.

About ten years ago, I read a series of science-fiction novels by Robert J. Sawyer called The Neanderthal Parallax. The first novel, Hominids, won the coveted Hugo Award in 2003. It opens with a scientist, Ponter Boddit, as he conducts an experiment using an advanced quantum computer. Only Boddit is not just a simple scientist, he’s a Neanderthal living on a parallel Earth where the Neanderthal survived to the modern era, rather than us homo sapiens.

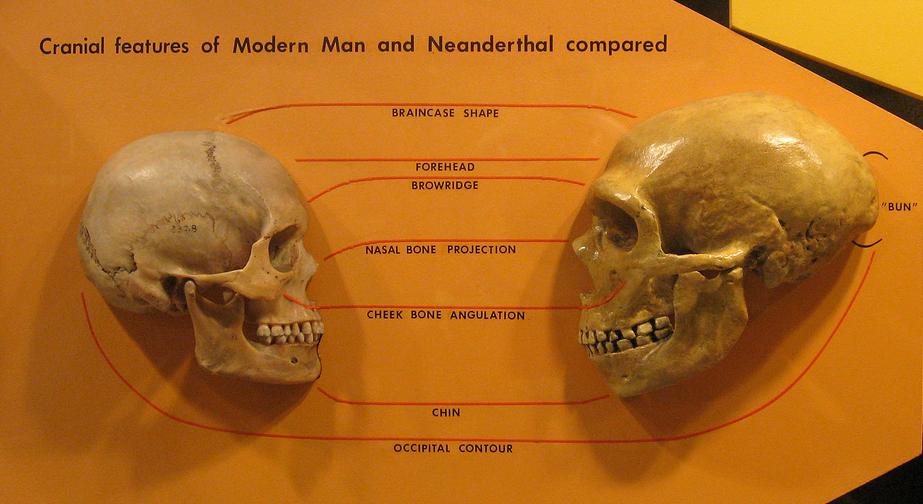

Contrary to common misconception, the Neanderthal were not our progenitors, but a species of human which co-existed with us for millennia before mysteriously dying off about 28,000 years ago, during the last ice age. Based on DNA evidence, modern humans and Neanderthal shared a common ancestor about 660,000 years in the past.

Scientists debate the causes of the Neanderthal extinction. Were they less adaptable to the drastic climate changes happening at the time? Did conflict with our own species result in their genocide? Perhaps, as some researchers have proposed, homo sapiens survived over their Neanderthal cousins because we had a greater propensity for cooperation.

In any case, the traditional idea of Neanderthal as dumb, lumbering oafs is not borne out by the latest research, and interbreeding between Neanderthal and modern humans was actually pretty common. In fact, those of us coming from European stock have received between one and four percent of our DNA from our Neanderthal forebearers.

The point I’m trying to make is that it could as easily have been our species, homo sapiens, which died off, leaving the Neanderthal surviving into the modern age instead.

This is the concept author Robert Sawyer plays with in his trilogy of novels. Sawyer’s main character, the Neanderthal scientist Ponter Boddit, lives in such an alternate world. In the novel, Boddit’s quantum experiment inadvertently opens a door to a parallel world — our own — and this sets up the story for the rest of the series.

The novels gained such critical praise at the time of their publication not just because of their seamless weaving of science and story on top of a clever premise, but also because of the thought Sawyer put into the culture of these Neanderthal living on an alternate Earth.

The Neanderthal, according to archeologists, were more resilient and physically stronger than their homo sapien cousins. A single blow from a Neanderthal is enough to kill a fellow citizen, and in consequence the Neanderthal of Sawyer’s novels have taken drastic steps to reduce violence in their society. Any incident of serious physical violence results in the castration of the implicated individual and all others who share at least half his genes, including parents, siblings and children. In this way, violence has slowly been weeded out of the Neanderthal gene pool.

About three decades before the start of the first novel, Hominids, a new technology is introduced into Neanderthal society to further curb crime and violence. Each Neanderthal child has something called a “companion implant” inserted under the skin of their forearm. This implant is a recording device which monitors every individual constantly with both sound and video. Data from the device is beamed in real-time to a database dubbed the “alibi archive,” and when there is any accusation of criminal conduct, this record is available to exonerate or convict the individual being charged.

Strict laws govern when and by whom this information can be accessed. Think of our own laws regarding search and seizure outlined in the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution.

By these two elements — a companion implant which monitors each citizen 24/7, and castration as the only punishment for convicted offenders — violence and crime have virtually been eliminated from Neanderthal society, and incarceration has become a thing of the past.

While I’m not advocating for the castration of all violent criminals and their relations, the idea of a companion implant is something that has stuck with me in the years since I first read Sawyer’s novels.

Could such a device eliminate crime and violence from our own society?

Let’s take a closer look at this idea before dismissing it completely. One of the first objections is about the loss of privacy. Constant surveillance? Even in the bathroom? Isn’t that crazy?

Consider this: according to a 2009 article in Popular Mechanics magazine, there are an estimated 30 million security cameras in the United States, recording more than four billion hours of footage every week, and that number has likely climbed significantly in the nine years since the article was published.

Doubtless there’s not a day that goes by that you are not captured by some camera: at the bank, the grocery store, passing a traffic light, going through the toll booth on the interstate. Even standing in your own backyard, you are not invisible to the overhead gaze of government satellites. We are already constantly under surveillance.

Add to this the proliferation of user-generated content on sites like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. How often do you show up in the background of someone else’s selfie or video podcast?

Oh, you might say, but these are random bits, scattered across the Internet from many different sources. We are protected by the very diffusion of this data!

To a human being, perhaps this is true, but for a computer, the Internet is one big database, and more and more, artificial intelligences are used to sift through this data instead of humans.

Take, for example, Liberty Island, home of the Statue of Liberty. A hot target for terrorists, the most visited location in America is also the most heavily surveilled. With hundreds of cameras covering every square inch of the island, you would need an army of human operators to watch all the screens for anything out of place. This is obviously unfeasible, so they have turned to the latest in artificial intelligence instead. AI technology can identify individuals via facial recognition, detect if a bag has been left unattended, or send an alert to its human operators if it detects anything amiss.

And we are not only surveilled via strategically placed security cameras either. Our credit card receipts, phone calls, text messages, Facebook posts and emails all leave behind a digital trail of our activities. We are simply not aware of how thoroughly our lives are digitally documented because that information is held by many different sources across a variety of mediums.

For example, so many men have been caught in their wandering ways by evidence obtained from interstate E-ZPass records, it’s led one New York divorce attorney to call it “the easy way to show you took the off-ramp to adultery.”

And with the advancements in artificial intelligence, especially deep learning (which I wrote about last week), this information is becoming more accessible to more people as computer intelligences become better at sifting through it.

We have, in essence, created the “companion implant” of Sawyer’s novels without anyone ever having agreed to undergo the necessary surgery.

The idea of having an always-on recording device implanted into our arms at birth, which watches everything we do, sounds like a crazy idea until you sit down and realize we’re heading in that direction already.

The very aspect that has, up ‘til now, protected us from this constant surveillance — the diffusion of the data, the fact that it’s spread out among many different sources, and the great quantity of data which makes it difficult for humans to sift through — will soon cease to be a limiting factor in the coming age of AI. Instead, that diffusion will begin to work against us, since it is difficult to adequately control access to data collected by so many different entities.

A personal monitoring device, which records every single moment of our day, would be preferable to the dozens of cameras and other methods which currently track us. A single source could be more easily protected, and laws governing access to its data could be more easily controlled.

Instead, we have built a surveillance society where privacy dies by a thousand cuts, where the body politic lies bleeding in the center lane of the information superhighway, while we stand around and complain about the inconvenience of spectator slowing.

Eric W. Austin writes about technology and community issues. He can be reached by email at ericwaustin@gmail.com.

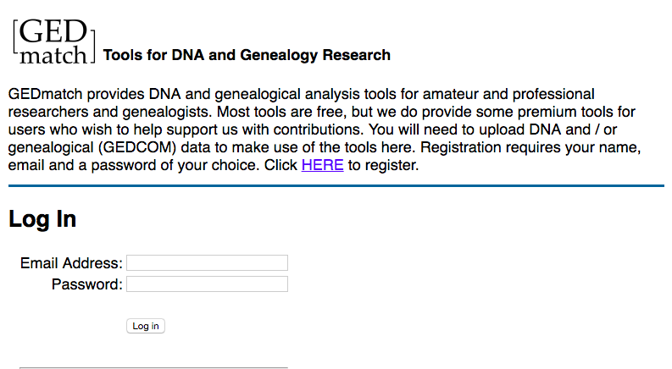

This is the service investigators used to finally track down the Golden State Killer. The suspect hadn’t uploaded his own genetic profile to the database, but distant relatives of his had. Once the investigation could identify individuals related – however distantly – to the suspect, it took only four months to narrow their search down to the one person responsible. Then it was a simple exercise of obtaining a DNA sample from some trash the suspect discarded and matching it to samples from the original crime scenes.

This is the service investigators used to finally track down the Golden State Killer. The suspect hadn’t uploaded his own genetic profile to the database, but distant relatives of his had. Once the investigation could identify individuals related – however distantly – to the suspect, it took only four months to narrow their search down to the one person responsible. Then it was a simple exercise of obtaining a DNA sample from some trash the suspect discarded and matching it to samples from the original crime scenes. The availability of genetic testing for the average consumer was just a distant dream when HIPAA passed in 1996. The internet was still in its infancy. A lot has changed in the last 22 years, and our laws have not kept up.

The availability of genetic testing for the average consumer was just a distant dream when HIPAA passed in 1996. The internet was still in its infancy. A lot has changed in the last 22 years, and our laws have not kept up.