TECH TALK: How technology could save our Republic

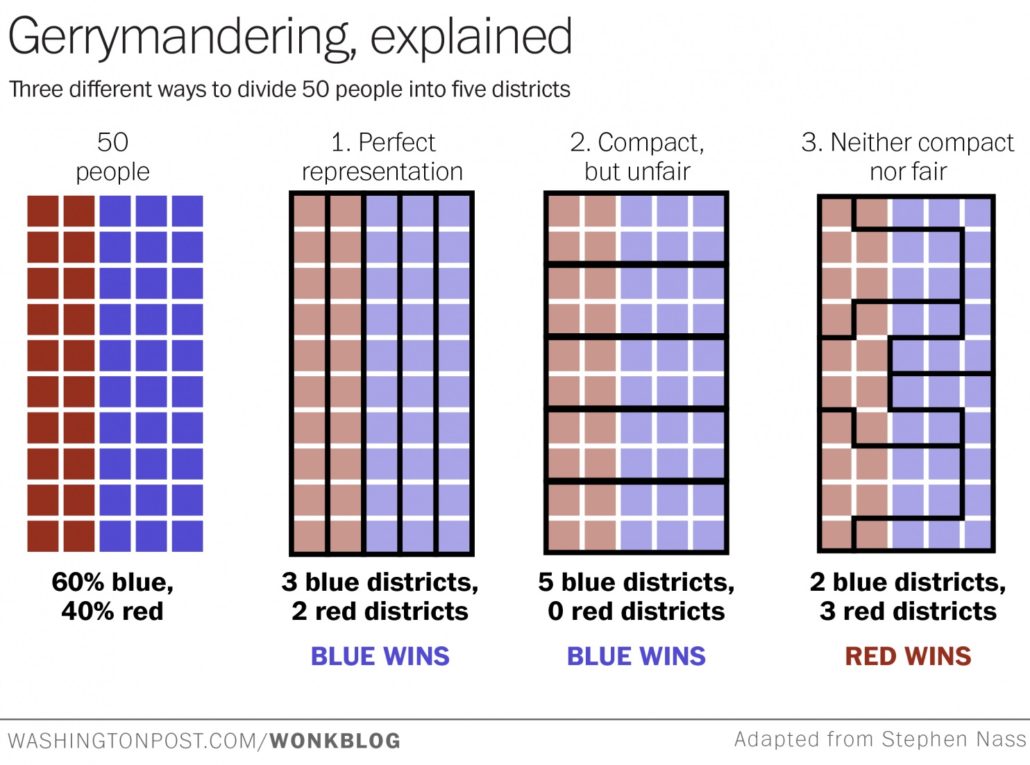

Gerry-mandering explained. (image credit: Washington Post)

ERIC’S TECH TALK

ERIC’S TECH TALK

by Eric W. Austin

Computer Technical Advisor

Elbridge Gerry, second-term governor of Massachusetts, is about to do something that will make his name both legendary and despised in American partisan politics. It’s two months after Christmas, in a cold winter in the year 1812.

Typical of a politician, the next election is forefront in his mind. And Gerry has reason to worry.

Elections in those days were a yearly affair. Between 1800 – 1803 Gerry had lost four elections in a row to Federalist Caleb Strong. He didn’t dare run again until after Strong’s retirement in 1807. Three years later, though, Elbridge Gerry gathered his courage and tried again.

This time he won.

Gerry was a Democratic-Republican, but during his first term the Federalists had control of the Massachusetts legislature, and he gained a reputation for championing moderation and rational discourse.

However, in the next election cycle his party gained control of the Senate and things changed. Gerry became much more partisan, purging many of the Federalist appointees from the previous cycle and enacting so-called “reforms,” increasing the number of judicial appointments, which he then filled with Republican flunkies.

The irony of this is that Gerry had been a prominent figure in the U.S. Constitutional Convention in the summer of 1787, where he was a vocal advocate of small government and individual liberties. He even angrily quit the Massachusetts’ ratifying convention in 1788 after getting into a shouting match with convention chair, Francis Dana, primarily over the lack of a Bill of Rights. (The first 10 amendments later became the Bill of Rights.)

But none of this is what Elbridge Gerry is remembered for.

That came in the winter of 1812 when he signed into law a bill redrawing voting districts in such a way that it gave electoral advantage to his own Democratic-Republican party.

The move was highly successful from a political standpoint, but unpopular. In the next election, Gerry’s Democratic-Republican party won all but 11 seats in a State Senate that had – only the year before – been controlled by the Federalists. This, despite losing a majority of the seats in the House by a wide margin, and the governorship as well as: his old Federalist nemesis, Caleb Strong, came out of retirement to defeat him.

According to a legendary account from the period, someone posted a map of the newly-drawn districts on the wall in the offices of the Boston Gazette. One of the editors pointed to the district of Essex and remarked that its odd shape resembled a salamander. Another editor exclaimed, “A salamander? Call it a Gerry-mander!”

Thus the first “Gerry-mander” was born.

Today the process of redrawing district boundaries in such a way as to favor one party over another is referred to as “gerrymandering.”

It is mandated in the Constitution that states be divided into districts of equal population. So, every ten years when a census is taken, states redraw voting districts based on population changes. In many states, the party that controls the state legislature at the time also dictates this. Predictably, gerrymandering is most dominant in these states.

By strategically drawing the district lines to give the ruling party election-advantage, that party can maintain their legislative power even if the majority of the population moves away from them in the following years.

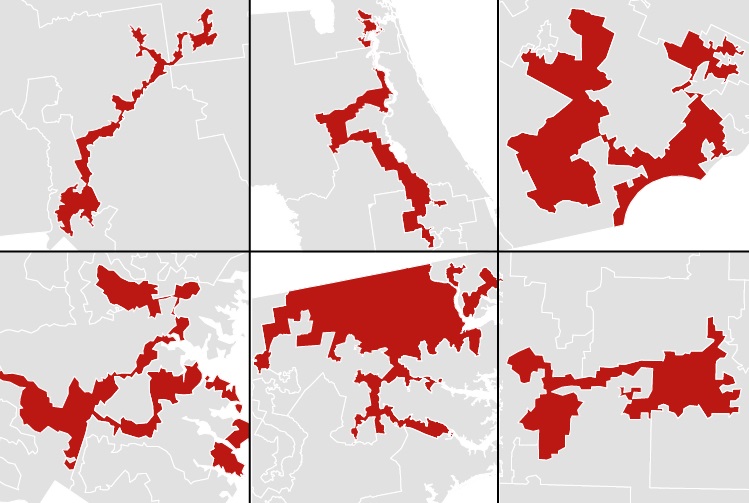

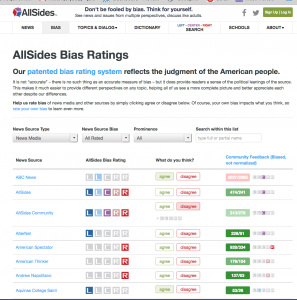

According to a 2014 study conducted by The Washington Post, Republicans are currently responsible for drawing eight out of ten of the most gerrymandered districts in the U.S. This has resulted in the Democrats being under-represented by about 18 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives “relative to their vote share in the 2012 election.”

The most gerrymandered districts in the United States. (image credit: Washington Post)

Maine is one of the few states that has given this decision to an independent, bipartisan commission instead. That commission then sends a proposal for approval to the state legislature. Of course, we have it a bit easier, with only two districts to worry about.

For much of the nation, gerrymandering is still one of the most prevalent and democratically destructive practices in politics today.

It’s also notoriously difficult to eradicate.

The problem is that someone has to decide on the districts. And everyone is biased.

Even in the few cases where legal action has been brought against an instance of partisan gerrymandering, how does one prove that bias in a court of law? The quandary is this: in order to prove a district was drawn with bias intent, one must first provide an example of how the district would look if drawn without bias. But since all districts are drawn by people, there is no such example to use.

Because of this difficulty, in 2004 the Supreme Court ruled that such a determination constitutes an “unanswerable question.”

But that may be about to change.

There is currently a major redistricting case before the Supreme Court. Professor Steve Vladeck, of Texas University’s School of Law, calls it “the biggest and most important election law case in decades.” It involves a gerrymandered district in Wisconsin.

The reason the courts are now taking these cases more seriously is because of recent advances in computer-powered analytics: technology may finally provide that elusive example of an unbiased district.

This week, August 7-11, a team of mathematicians at Tufts University is holding a conference on the “Geometry of Redistricting” to look at this very problem.

A number of mathematical algorithms have already been proposed to remove the human-factor from the process of redistricting.

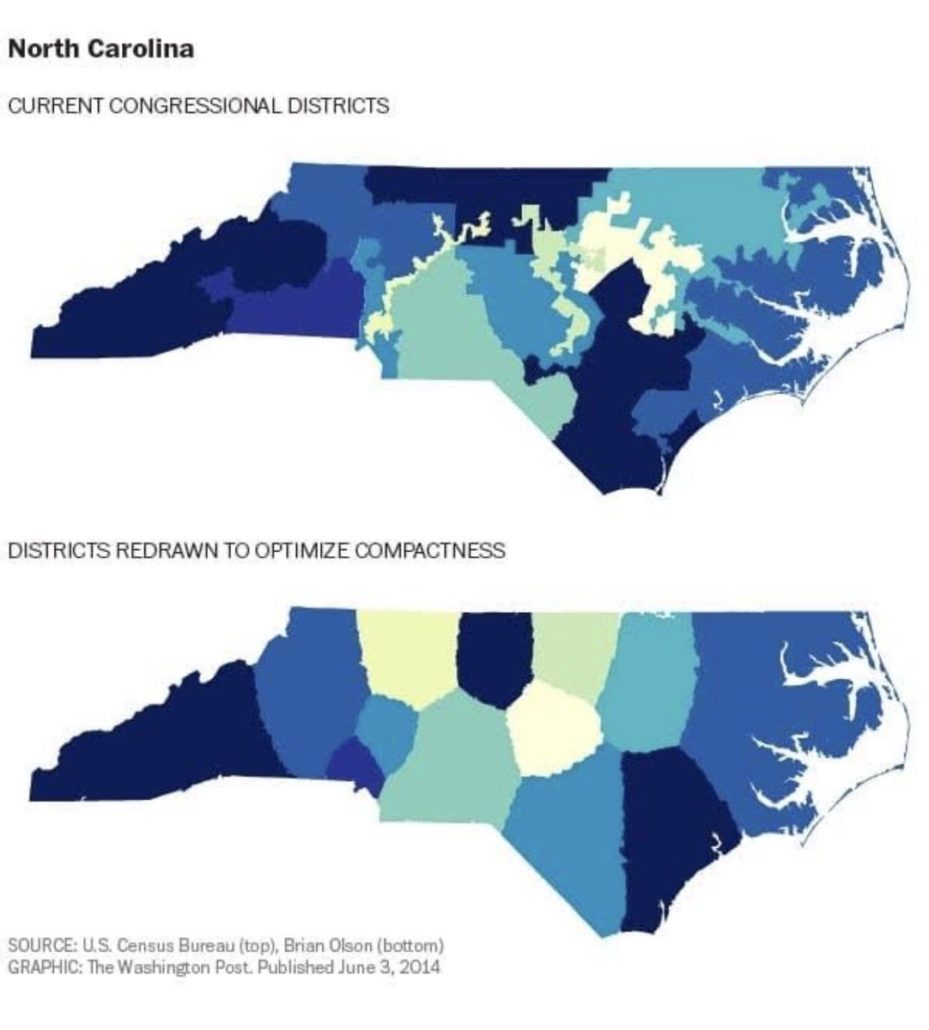

Brian Olson, a software engineer from Massachusetts, has developed an algorithm which draws districts based on census blocks. His approach aims to make districts as compact as possible while maintaining neighborhood integrity.

The debate is still going on about which factors are most essential to a redistricting algorithm, but eventually one method will become standard and the days of gerrymandering will be over.

Poor Elbridge Gerry. After losing the Massachusetts governorship, he became vice president under James Madison and then died in office, becoming the only signer of the Declaration of Independence to be buried in America’s capital. But he’s mostly remembered for the despised political practice that bears his name. Hopefully, soon even that will be forgotten.

Good riddance Elbridge Gerry, I say. Good riddance, sir!

The difference a computer makes: The top image shows the districts of North Carolina as they are drawn today. The bottom image are districts drawn by an unbiased computer algorithm. Which looks more fair to you? (image credit: Washington Post)

And it got me thinking. Is there any law on the books requiring an Artificial Intelligence to tell you it is an artificial intelligence? After a bit of research, I found

And it got me thinking. Is there any law on the books requiring an Artificial Intelligence to tell you it is an artificial intelligence? After a bit of research, I found

One of the new ways kids have found to stay inside during beautiful summer days in Maine, is with a new activity called “binge-watching.” Essentially, binge-watching is the practice of watching multiple episodes of a single TV show in one sitting.

One of the new ways kids have found to stay inside during beautiful summer days in Maine, is with a new activity called “binge-watching.” Essentially, binge-watching is the practice of watching multiple episodes of a single TV show in one sitting. Each episode deals with a single cassette tape, which involves a revelation about how one of her fellow classmates has wronged her, leading to her ultimate decision to kill herself.

Each episode deals with a single cassette tape, which involves a revelation about how one of her fellow classmates has wronged her, leading to her ultimate decision to kill herself. That doesn’t sound like much fun, does it? Why would anyone want an Internet that works this way?

That doesn’t sound like much fun, does it? Why would anyone want an Internet that works this way? Certain other applications will also transfer data between the Internet and your computer, like games being played online, programs downloading updates, or certain programs that have specific network functions such as FTP programs for updating websites, or P2P (Peer-to-Peer) file-sharing applications for downloading large files.

Certain other applications will also transfer data between the Internet and your computer, like games being played online, programs downloading updates, or certain programs that have specific network functions such as FTP programs for updating websites, or P2P (Peer-to-Peer) file-sharing applications for downloading large files.

A VPN service accepts your network communications, and then sends them back out to the Internet using its own IP Address in place of yours. In this way, none of your activities can be linked back to your personal computer. Instead, they would link back no further than your VPN server, which millions of other people also use.

A VPN service accepts your network communications, and then sends them back out to the Internet using its own IP Address in place of yours. In this way, none of your activities can be linked back to your personal computer. Instead, they would link back no further than your VPN server, which millions of other people also use. 2. Join the Conversation! Got a grievous grumble caught in your gullet? Unlike the paper, the website allows you to post your comments on every story! Just remember that we at The Town Line follow the BNBR (Be Nice, Be Respectful) policy, and any comments that breach this will not be approved!

2. Join the Conversation! Got a grievous grumble caught in your gullet? Unlike the paper, the website allows you to post your comments on every story! Just remember that we at The Town Line follow the BNBR (Be Nice, Be Respectful) policy, and any comments that breach this will not be approved!