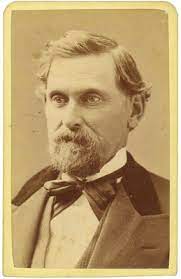

Brigadier General John Chandler

Brigadier General John Chandler, profiled in the February 24 issue of The Town Line, was not the only area resident to have served in the Revolutionary army and again in 1812. Nor were these two wars the end of disagreements between the United States, and specifically the State of Maine, and Britain and British-controlled Canada.

* * * * * *

According to an on-line genealogy, Thaddeus Bailey (Nov. 28, 1759 – March 4, 1849) was born in Newbury, Massachusetts, served in the Revolutionary War from Lincoln County, lived in Palermo for some years and served in the War of 1812 while living in Albion.

In 1778, he was part of a Lincoln County troop sent to Providence. On June 30, 1779, he officially enlisted as a private in Capt. Timothy Heald’s company, Col. Samuel McCobb’s regiment.

(McCobb [Nov. 20, 1744 – July 30, 1791], who later became a brigadier general, was born and died in Georgetown. He had served at Bunker Hill, and led the Lincoln County militia in the unsuccessful July-August 1779 Penobscot expedition, in which Bailey participated for two months and 27 days, according to the on-line source.)

Bailey was discharged Sept. 25, 1779. The genealogy says he received a Revolutionary veteran’s pension in the amount of $30.65 annually, starting May 3, 1831.

In 1783, Bailey married Mary Knowlton, of Wiscasset. The couple moved inland to the north part of Pownalbourough, which an on-line source says is now Alna, where the first three of their 11 children were born.

In 1795 they moved inland again; Millard Howard’s Palermo history cites an 1809 record confirming on-line reports that Bailey bought (for $110) 100 acres in Sheepscot Great Pond Settlement, now Palermo.

In 1801, Bailey was among a large number of residents who signed a two-part petition to the Massachusetts General Court. The petition asked to have the settlement incorporated as a town to be named Lisbon, bounded by Harlem (later China), the Sheepscot River and Davistown (later Montville, from which Liberty was separated in 1827).

Further, the petitioners wrote, “from the new and unsettled state of their country they have a great proportion of roads to make and maintain within their aforesaid bounds and also at least ten miles of road to maintain outside of their aforesaid limits which road leads to the head of navigation on Sheepscot river, their nearest market. Wherefore, your petitioners pray that they may be exempted from paying State taxes during the term of five years next ensuing….”

(Howard went on to explain that while the Massachusetts legislators considered the request, another Maine town was incorporated as Lisbon. Sheepscot Great Pond’s clerk was Dr. Enoch Palermo Huntoon; and given the popularity of using famous cities’ names – like Lisbon — for new Maine towns, the petitioners chose Palermo as the fall-back name.

Palermo was incorporated June 23, 1804. Howard did not say how the tax exemption request was received.)

Mary Bailey’s on-line genealogy says the Baileys “were early members of the Baptist Church of Palermo, founded in 1804.”

The family soon moved again, and again inland. Census records from 1810 and 1820 show Bailey living in Fairfax (Mary died in January 1816).

Bailey served briefly and uneventfully in the War of 1812, going to Belfast Sept. 3, 1814, and coming back Sept. 14. Howard listed him among the privates in the Palermo militia (apparently he enrolled or re-enrolled there rather than in Fairfax). By then he would have been coming up on his 55th birthday.

In the 1830 and 1840 censuses, Bailey is still in the town that had become Albion in 1824. The Roll of Pensioners mentioned on line says in 1841, he was 80 years old and had returned to Palermo.

* * * * * *

Dean Bangs’ (May 31, 1756 – Dec. 6, 1845) Revolutionary service was summarized in the Jan. 20 issue of The Town Line. By 1812, Bangs was living in Sidney and doing business in Waterville.

In Whittemore’s history of Waterville, Bangs’ grandson, Isaac Sparrow Bangs, wrote in the military chapter that in the War of 1812 Bangs raised a company of men from Waterville and Vassalboro to serve in Major Joseph Chandler’s Artillery Company. The company was held at Augusta from Sept. 12 to Sept. 24, 1814, the period during which other Kennebec Valley units went to the coast to meet a British landing that never occurred.

(Your writer has spent a great deal of time trying to find the relationship, if any, between General John [Feb. 1, 1762 – Sept. 25, 1841] and Major Joseph Chandler. One of several on-line Chandler genealogies lists the 12 children of Joseph Chandler III and Lydia [Eastman] Chandler as including Joseph IV [1755-1785] and John [1762 – 1840]; and 1840 is as close as genealogies sometimes get to the 1841 found in on-line sources. However, if this Joseph Chandler died young in 1785, he cannot have led an artillery unit in the War of 1812.)

* * * * * *

Michael McNally (about 1752 – July 16, 1848) must have been among the oldest Revolutionary War veterans to fight in the War of 1812. An on-line family history calls him “a man of superior education and strong intellectual powers.”

The history says he was born in Ireland and emigrated with his parents to Pennsylvania, where his father was wealthy enough to provide for his son’s education. On May 13, 1777, he is recorded as enlisting as a gunner in the state’s artillery regiment.

On Jan. 1, 1781, McNally received “depreciation pay,” described online as negotiable, interest-bearing certificates given to military personnel to compensate for the decreased value of United States currency during their wartime service. Family stories say he left the army and served on some kind of armed ship, “whether a man-of-war or a privateer is unknown.” Later, he received a pension as a Revolutionary veteran.

Around 1784, he moved to the Kennebec Valley. In 1785, he married his first wife, Susan Pushaw (1768-1811), of Fairfield. The couple settled in the part of Winslow that became Clinton in 1795; McNally built a log cabin on the Sebasticook, the family history says.

The McNallys had nine children between 1786 and 1809. Susan Pushaw’s on-line genealogy spells her father’s name Pochard and says he was born in France. Michael and Susan’s children’s names are variously spelled Mcnally, Mcnelly, Mcnellie and Mcknelly).

Despite being a single father, when the War of 1812 was declared, the family history says: “Michael’s martial spirit was aroused, and although a man of sixty years he enlisted at Clinton, May 17, 1813, in Capt. Crossman’s company of the Thirty-fourth Regiment, U.S. Infantry, and marched to the frontier. He received a severe wound in the collarbone at Armstrong, Lower Canada, in Sept., 1813, while serving in detachment under the command of Lieut.-Col. Storrs. He was mustered out in July, 1815. For this service he received a pension.”

McNally married for the second time about 1830, to a Pittsfield widow, Jane Varnum Harriman. Her death date is unknown, but the family history says McNally spent his last years with his sons Arthur (1796-1879) and William (1798 or 1799-1886).

William McNally was a farmer in Benton. His wife, Martha Roundy (Sept 13, 1803 – summer of 1903) was the daughter of Job and Elizabeth or Betsey (Pushaw or Pushard) Roundy and the source of much of the information in the family history.

* * * * * *

Louis Hatch’s 1919 history of Maine includes a summary of the final settlement of the boundary between the eastern United States and adjoining Canadian provinces, an issue that troubled relations between the two countries from 1783 until 1842.

The St. Croix River had been defined as the boundary line by the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolution. But the St, Croix has three branches, and the two countries disagreed over which was the “real” St. Croix.

The Jay Treaty of 1794 (properly, the Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America) created a three-man commission whose members unanimously and permanently defined the St. Croix River boundary on Oct. 25, 1798, Hatch wrote.

The boundary north and west from the head of the St. Croix still remained undefined. The United States claimed an area reaching north almost to the St. Lawrence River; Britain, on behalf of Canada, claimed a good part of what is now northern Maine.

The Dec. 24, 1814, Treaty of Ghent that ended the War of 1812 included a clause establishing a commission to define this part of the boundary, from the source of the St. Croix River around the “northwest angle of Nova Scotia,” and south and west along the highlands that separated the watersheds of the St. Lawrence from the watersheds of rivers that ran into the Atlantic, all the way to the headwaters of the Connecticut River.

The treaty further provided that if the two commissioners disagreed or failed to act, the boundary question should be submitted to “a friendly sovereign or State.”

The commission was activated in the spring of 1816. Hatch wrote that after five years, its members had not even agreed on a map showing what areas each country claimed. The commission dissolved.

On Sept. 29, 1827, the United States and Great Britain agreed to submit the dispute to the King William I of the Netherlands. Hatch summarized the king’s responsibility: to interpret the 1783 treaty provisions by fitting them to the geography. The king needed to locate for the disputants the headwaters of the St. Croix, the “northwest angle of Nova Scotia,” the significant highlands and the “Northwesternmost head of the Connecticut River.”

King William issued his judgment on Jan. 10, 1831. Hatch called it “a compromise, pure and simple.”

Between the 1816 commission’s creation and King William’s 1831 report, Maine had become a state, with its own legislature and representation in the United States Congress. An increasing number of United States citizens were expanding settlements in Maine, as far north as the St. John River valley.

The 1831 Maine legislature established a committee to review King William’s judgment; the ensuing resolutions strongly condemned it. In June 1832, the United States Senate refused to ratify it.

The 1831 Maine legislature also incorporated the Town of Madawaska on the St. John River, including, Hatch wrote, the present Madawaska south of the river and some land north of the river. The area north of the river is now Upper Madawaska, New Brunswick, he said.

Hatch quoted part of Governor Samuel Smith’s 1832 annual message summarizing what happened next. The governor said Madawaska residents had organized their town, apparently acting before the state’s approval, and had elected town officials and a legislative representative. New Brunswick officials, “accompanied with a military force,” had arrested and imprisoned many residents.

Smith had appealed to the United States government. Though neither he nor federal authorities were sure the Madawaska residents had acted legally, President Andrew Jackson promptly intervened, and the prisoners were freed.

In following years, Maine governors and legislatures continued to push for a resolution of the boundary issue that would get the British out of the state. Hatch quotes from an 1837 Maine legislative resolution that referred to “British usurpations and encroachments” and said:

“Resolved, that [British] pretensions so groundless and extravagant indicate a spirit of hostility which we had no reason to expect from a nation with whom we are at peace.”

How that peace turned into a war, or at least a pseudo war, will be next week’s topic.

Main sources

Hatch, Louis Clinton, ed., Maine: A History 1919 (facsimile, 1974).

Howard, Millard, An Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine (second edition, December 2015).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902)

Website, miscellaneous.

The 44th annual Maine Student Film + Video Festival (MSFVF) is currently accepting submissions until June 15. All Maine students grades K-12 are eligible to enter for free. Films will be judged by category: Narrative, Documentary, and Creative (animated, experimental, etc.), and by age group: Grades K-5; Grades 6-8; Grades 9-12.

The 44th annual Maine Student Film + Video Festival (MSFVF) is currently accepting submissions until June 15. All Maine students grades K-12 are eligible to enter for free. Films will be judged by category: Narrative, Documentary, and Creative (animated, experimental, etc.), and by age group: Grades K-5; Grades 6-8; Grades 9-12.

News reports of Russia’s attack on Ukraine may encourage concerned individuals to reach out and help victims affected by the conflict.

News reports of Russia’s attack on Ukraine may encourage concerned individuals to reach out and help victims affected by the conflict.

Plant a tree and help the Earth! The Waterville Public Library (WPL) is celebrating Earth Day this spring by participating in the 13th Annual Neighborhood Forest free tree program, whose aim is to provide free trees to kids every Earth Day! To get one, parents can fill out the online registration form.

Plant a tree and help the Earth! The Waterville Public Library (WPL) is celebrating Earth Day this spring by participating in the 13th Annual Neighborhood Forest free tree program, whose aim is to provide free trees to kids every Earth Day! To get one, parents can fill out the online registration form.

Spectrum Generations, Central Maine’s Agency on Aging, has entered into a contract with Capital Area New Mainers Project to expand equity of access to Older Americans Act services to New Mainers in central Maine. This partnership will provide New Mainers who are caregivers or who are over 60 with culturally competent delivery of services including information and referral services, benefits enrollment, caregiver support and respite, and meals on wheels.

Spectrum Generations, Central Maine’s Agency on Aging, has entered into a contract with Capital Area New Mainers Project to expand equity of access to Older Americans Act services to New Mainers in central Maine. This partnership will provide New Mainers who are caregivers or who are over 60 with culturally competent delivery of services including information and referral services, benefits enrollment, caregiver support and respite, and meals on wheels.