Up and Down the Kennebec Valley: Arnold’s expedition

by Mary Grow

by Mary Grow

Before continuing upriver, this subseries will summarize the one Revolutionary event that did have a direct impact on towns along the Kennebec River. That was the fall 1775 American expedition intended to take Québec City from the British (who had taken it from the French in September 1759).

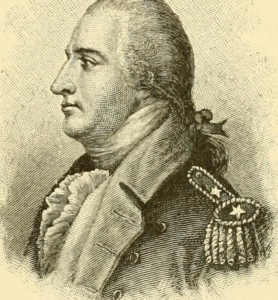

In September and October of 1775, Colonel Benedict Arnold led an army of about 1,100 men from Newburyport, Massachusetts, up the Kennebec River, across the Height of Land and down the Chaudiere River to the St. Lawrence.

Among documents at Fairfield’s Cotton Smith House, home of the Fairfield Historical Society, is a 1946 Bangor Daily News article quoting Louise Coburn’s Skowhegan history: she said the army consisted of 10 New England infantry companies and three companies of riflemen from Pennsylvania and Virgina.

(The 1890 Cotton Smith House has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1992.)

Scattered partial reenactments of this “march to Québec” are being organized in the fall of 2025. Among organizing groups is the Arnold Expedition Historical Society, headquartered in Pittston’s Reuben Colburn house (built in 1765, a state historic site and on the National Register of Historic Places since 2004).

A personal note: your writer learned about Arnold’s march to Québec when she was very young, through the historical novels of Maine writer Kenneth Roberts. Arundel, published in 1930, tells of the expedition and the unsuccessful attack on the city. Rabble in Arms, published in 1933, is the story of the army’s retreat down the St. Lawrence and Richelieu rivers and Lake Champlain.

Roberts highly admired General Arnold. Each novel is told from the perspective of a participant looking back to his youth, so there are references to Arnold’s subsequent switch to the British side; but his conduct in 1775 is consistently praised, and his detractors damned.

Captain Peter Merrill, of Arundel, Maine, fictional narrator of Rabble in Arms, explained that he intended to write a history of part of the war, and found Arnold “an inseparable part” of his project. He wrote:

“Benedict Arnold was a great leader: a great general: a great mariner: the most brilliant soldier of the Revolution. He was the bravest man I have ever known. Patriotism burned in him like an unquenchable flame.”

Why, then, did Arnold switch sides in September 1780? To Roberts (and a few others) the answer is, again, patriotism. Having witnessed the incompetence, corruption and general worthlessness of the Congress that mismanaged the war, costing – wasting – too many lives, Arnold believed the country’s salvation required re-submitting to British rule, with competent Americans as administrators, until the colonies were strong enough to revolt successfully.

* * * * * *

Arnold’s army left Massachusetts on Sept. 19, 1775; reached the mouth of the Kennebec the next day; and stopped first at Gardinerstown (later Pittston), south of Augusta. Here 200 wooden bateaux had been hastily built in Reuben Colburn’s shipyard at Agry Point (named for a 1774 settler), on the east bank of the Kennebec.

(An on-line map shows the Colburn House on Arnold Road, and Agry Point Road running south from the south end of Arnold Road and dead-ending on the south side of Morton Brook.)

According to Colburn House information on the Town of Pittston’s website, Colburn had suggested attacking Québec via the Kennebec and had sent General George Washington “critical information.” Given only about three weeks’ notice to provide the bateaux, he had had to use green lumber, which did not hold up well; the boats leaked copiously, and fell apart under rough handling, on the water and on portages.

The website says Colburn himself and some of his crew went upriver with the troops, “carrying supplies and repairing the boats as they traveled.”

Henry Kingsbury, in his 1892 Kennebec County history, wrote that the army moved immediately upriver to Fort Western in future Augusta, where Arnold arrived on Sept. 21. For more than a week, he and some of his officers stayed with Captain James Howard at the fort.

On the evening of Sept. 23, Kingsbury wrote (using Capt. Simeon Thayer’s diary of the expedition for his source), a soldier named John McCormick got into a fight with a messmate at the fort, Reuben Bishop, and shot him. A report in the January-February, 2022, issue of the Kennebec Historical Society’s newsletter says alcohol was involved.

A prompt court-martial ordered McCormick hanged at 3 p.m. Sept. 26. Arnold, however, intervened and forwarded the case to Washington, “with a recommendation for mercy.” The KHS report says McCormick “was sent to a military jail in Boston, where he ultimately died of natural causes.”

On a website called Journey with Murphy reached through Old Fort Western’s website, a descendant of Sergeant Bishop called him “the first casualty of the Arnold expedition.” She wrote that he was born Nov. 2, 1740 (probably in central Massachusetts); enlisted soon after the Battle of Lexington; and served at the siege of Boston before joining Arnold’s expedition.

By her account, McCormick’s quarrel was not with Bishop, but with his (McCormick’s) captain, William Goodrich. After McCormick was thrown out of the house where they were billeted, he shot back into it, hitting Bishop as he lay by the fireside.

Bishop was buried somewhere near the fort. Kingsbury believed Willow Street was later “laid out over his unheeded grave.” His descendant wrote that his body was moved to Fort Western’s cemetery, and was by 2024 in Riverside Cemetery.

On Sept. 24, 1775, James North wrote in his 1870 Augusta history, Arnold sent a small exploring party ahead to collect information about the proposed route. They went most of the way across the Height of Land. North said the party’s guides were Nehemiah Getchell and John Horn, of Vassalboro.

Alma Pierce Robbins mentions in her 1971 Vassalboro history several earlier histories. One, she said, referred to “Berry and Getchell who had been sent forward…,” implying that they were part of, or guides for, the scouting party.

Different sources list other local men as guides for parts of the expedition. WikiTree cites a 1979 letter from a descendant of Dennis Getchell, of Vassalboro (see last week’s article) saying Dennis and three of his brothers, John, Nehemiah and Samuel, were scouts for Arnold, with Arnold’s journals as the source of the information.

Rev. Edwin Carey Whittemore, in his 1902 centennial history of Waterville, also named Nehemiah Getchell and John Horn as guides for the exploring party. He added, quoting an unnamed source, that a man named Jackins, who lived north of Teconnet Falls, served as a guide for the expedition.

Major General Carleton Edward Fisher, in his 1970 history of Clinton, wrote that Jackins (Jaquin, Jakens, Jackens, Jakins, Jackquith) was a French (and French-speaking) Huguenot who came to Winslow via Germany around 1772. Fisher believed Arnold sent Jackins to Québec with a letter in November 1775, citing expedition records kept by Arnold and others.

(Your writer, extrapolating from other sources, guesses the letter was to supporters in and around Québec letting them know an expedition was on the way.)

Two Native guides, Natanis and Sabatis (Sabbatis, Sabbatus), are named in several accounts, and in Kenneth Roberts’ novel. Some sources identify them as Abenakis (also called Wabanakis), others specify the Abenaki/Wabanaki band called Norridgewocks. Some say the two men were brothers or cousins.

Robbins called them “guides of no mean ability.” Both spent time in Vassalboro, she wrote, and “there are a few reports of those settlers who actually knew these two Indians.” As of 1971, she said, Sabatis’ name was on a boulder on Oak Grove Seminary grounds. Natanis Golf Course, on Webber Pond Road, was named after the 18th-century Natanis.

North wrote that over the period between Sept. 25 and Sept. 30, Arnold’s men moved from Fort Western to Fort Halifax, some in the bateaux (with most of the supplies) and some marching along the east bank of the river on the rough road laid out in 1754, when the forts were built to deter attacks by Natives backed by the French.

Robbins cited an account that the whole army camped on both sides of the Kennebec, in Vassalboro “while their bateaux were being repaired”; and Arnold “was entertained” at Moses Taber’s house.

(Your writer found no readily available information on Moses Taber. He was probably one of the Tabers who were among Vassalboro’s early settlers. They were Quakers; Taber Hill, the elevation north of Webber Pond about half-way between the Kennebec River and China Lake, is named after them.)

In Winslow, according to Whittemore’s history, an early settler, surveyor, doctor and selectman named John McKechnie treated sick soldiers from Arnold’s army

Above Fort Halifax, there was a miles-long stretch of waterfalls and rapids. Here the men had either to unload the bateaux, carry them past the danger zone, bring up the supplies and reload the boats; or haul the loaded boats upriver, in waist-deep autumn-cold water, against a strong current, over a rocky bottom.

North quoted a letter Arnold sent to George Washington in mid-October in which he compared his men to “amphibious animals, as they were a great part of the time under water.”

Several sources say that while his army labored up-river, Arnold made his headquarters in the first house built in Fairfield, Jonathan Emery’s, a short distance north of the present downtown. The Fairfield bicentennial history says Arnold was there a week; a WikiTree biography says two weeks, during which Emery, a carpenter, helped repair some of the bateaux.

(There will be more about Jonathan Emery and his family in next week’s article.)

By the time the army reached Norridgewock Falls in early October, North wrote (referring to Dr. Isaac Senter’s journal), many of the boats were wrecked. Worse, the wooden casks of bread, fish and peas were soaked and the food ruined, leaving the men with little to eat for the rest of the journey but salt pork, flour and whatever game they could kill.

From Norridgewock, North wrote, it was forty miles to the Great Carrying Place where the army left the Kennebec to go overland to the Dead River. After a very difficult journey (described in more or less detail in numerous sources, including North), during which men died and several companies abandoned the expedition and went home, about 600 remaining soldiers reached the St. Lawrence River on Nov. 9.

They besieged Québec and, with reinforcements, attacked the city the night of Dec. 31 1775. They failed to overcome the defenders, and many men were killed, wounded (including Arnold) or captured.

* * * * * *

Kingsbury summarized one effect of the expedition on the Kennebec Valley in the first of his two chapters on military history. He wrote that “The rare beauty of the valley through which they passed, the waving meadows, the heavy forest growth, made a lasting impression” that was not erased by the much harder journey that followed. The post-war peace brought continued hardship and hunger in the valley as “famishing regiments of soldiers” seized any available food on their way to homes along the coast. It “brought, also, many of the members of the Arnold expedition back as permanent settlers.”

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870)

Local historical society collections

Websites, miscellaneous.