Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Waterville historic district – Part 5

by Mary Grow

Final two Main Street Historic District buildings Old Post Office & Seton Hospital

Returning to the 2016 enlargement of Waterville’s Main Street Historic District, the final two buildings included are the four-story Cyr Building/Professional Building, on the northeast corner of Main and Appleton streets at 177-179 Main Street (see its photo in the Sept. 15 issue of The Town Line); and the Elks Club, on the north side of Appleton Street.

The Professional Building, built in 1923, was designed in Art Deco style by the Portland firm of William Miller and Raymond Mayo. (The Aug. 25 The Town Line article described Main Street’s other Art Deco building, the 1936 Federal Trust Company Bank.) It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on Feb. 19, 1982.

The application, prepared in July 1981 by Frank A. Beard and Robert L. Bradley of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission, said “the local press” of 1923 called the building “the finest of the Waterville office buildings.” Beard and Bradley did not disagree, writing that both in 1923 and in 1981 it was “an outstanding structure in the downtown area.”

They called the Professional Building “a comparatively rare example for Maine of a very early Art Deco impulse in architecture with some features of the earlier Chicago commercial styles.” With 42 “office suites” in 30,875 square feet of floor space, it was “by far the largest such structure in the city” in 1923.

Beard and Bradley wrote that the building’s two facades, on Main and on Appleton streets, each had a street-level entrance “surmounted by low arches with elaborate low reliefs and shields.” There were five bays of large windows on the Main Street side and six on the Appleton Street side; the end bays thrust outward, “creating the effect of corner towers.”

In their 2016 application for the expanded Main Street district, Scott Hanson and Kendal Anderson described the steel and concrete frame of the building and the exterior “cast stone first story with buff tapestry brick on the upper stories of the south and west elevations, red brick on the south elevation, and modern metal cladding on the north elevation.”

The northeasternmost building in the expanded historic district is the Colonial Revival style Elks Club, at 13 Appleton Street, another Miller and Mayo design. Built in 1913/1914, the two-and-a-half story brick building sits on a raised basement concrete foundation, with stairs leading up to a projecting entrance.

The Elks Club has cast stone decorations and at the attic level, “four historic diamond paned windows.” Each window has “four panes of colored glass forming a larger diamond at the center,” and is set in “a projecting brick surround with a cast stone square at each corner.”

* * * * * *

Two other historic buildings in Waterville are outside the Main Street district, but since each gained historic recognition as a public building, your writer thinks it appropriate to describe them now.

* * * * * *

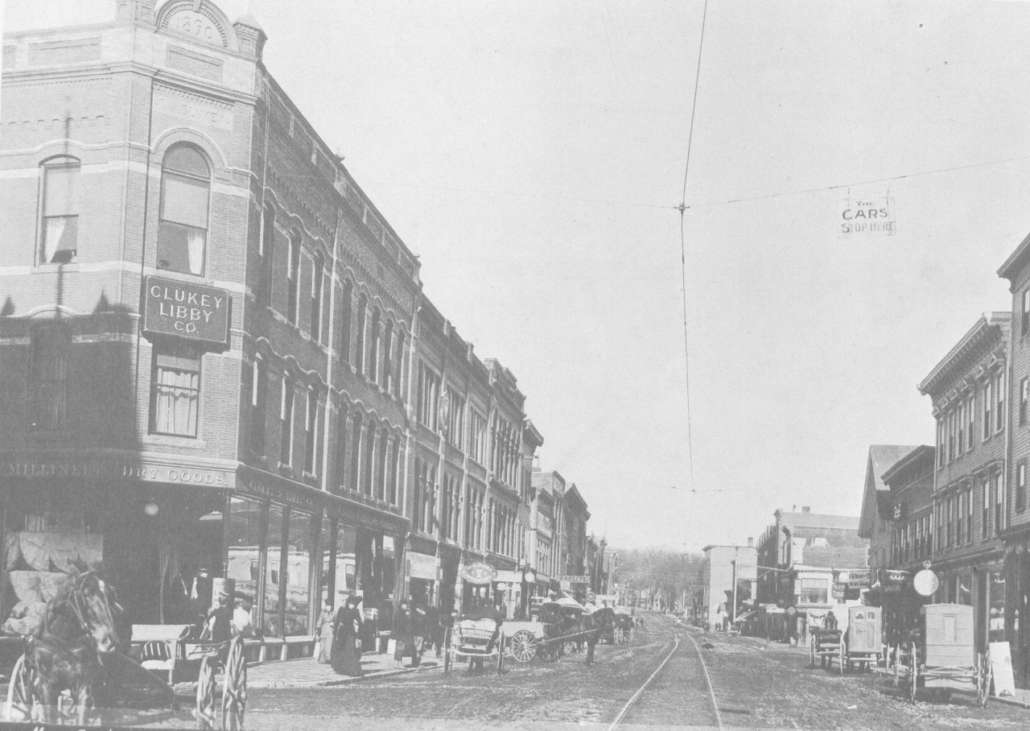

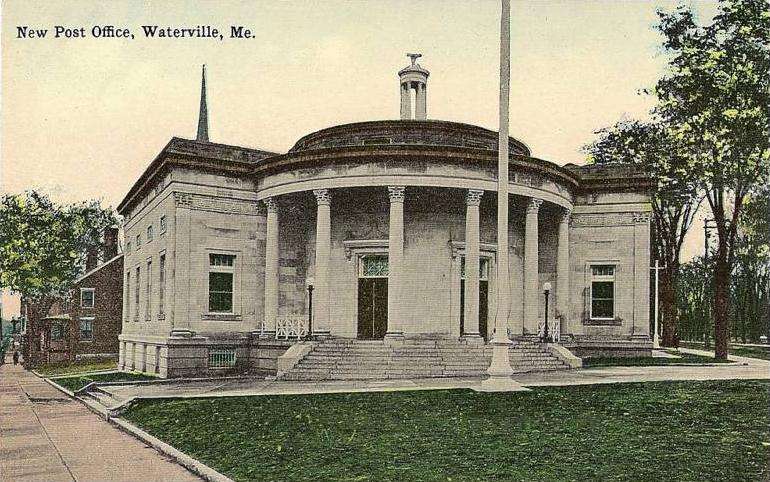

The older of the two is the former Waterville post office in the south angle of the five-way intersection of Main Street, Elm Street, Center Street, Upper Main Street and College Avenue. Mainely Brews now occupies its former basement, with a Main Street entrance.

Kingsbury wrote that Waterville’s first post office was established Oct. 3, 1796, with Asa Redington the first postmaster. He went on to list the successive postmasters, ending with Willard M. Dunn, appointed in 1889 for the second time (his first term was 1879 to 1885).

Kingsbury did not talk about post office buildings. Whittemore’s contributors suggested that the office moved from one rented space to another during the 19th century.

In his chapter on the early settlers, Aaron Plaisted mentioned the “little postoffice on the west edge of the Common,” where Abijah Smith was postmaster from 1832 (Kingsbury said 1833) to 1841. In 1902, according to Redington, the post office was in the ground floor of the W. T. Haines block, on the south side of Common Street (briefly mentioned in the Aug. 25 issue of The Town Line).

At that time, Redington wrote, the postmaster and his assistant supervised “seven clerks, five carriers and one substitute. The post office did $40,000 worth of business annually, and Redington predicted it would soon “be numbered among the first-class offices.”

The historic Old Post Office was built in 1911 – a Waterville timeline found on line says it opened in 1913 – and was added to the National Register of Historic Places April 18, 1977.

When Maine Historic Preservation Commission historian Frank A. Beard and graduate assistant Stephen Kaplan prepared the application for historic listing in October 1976, they wrote that the building was owned by the U. S. Postal Service and was unoccupied. Waterville’s College Avenue post office and federal building opened in 1976, according to the on-line timeline.

U.S. Treasury Department Architect James Knox Taylor designed the 1911 building. Taylor (October 11, 1857 – August 27, 1929) was the Treasury Department’s Supervising Architect from 1897 to 1912, and is credited with a long list of federal buildings.

Beard and Kaplan wrote that Waterville’s post office typified the early 20th century use of Greek Revival style for government buildings “and survives as perhaps the best of only a few such examples in Maine.”

They described the combination of a square block and a circular front that made the single-story stone building impressive, with on its front a “Corinthian colonnade of refined proportions and handsome detail. Similarly designed pilasters appear at the front corners of the block structure, symbolically unifying the block to the curve.”

The structure atop the flat roof is described as “a tall Corinthian cylindrical lantern, based in shape and character on the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens.” (Wikipedia has an illustrated article on this monument, built in 335/334 BCE in Athens and “reproduced widely in modern monuments and building elements.”)

* * * * * *

The Elizabeth Ann Seton Hospital at 30 Chase Avenue, on the west side of Waterville, was designed in 1963; its construction was finished in mid-1965. On July 11, 2016, it was approved for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

The application for national listing was prepared by Matthew Corbett, Scott Hanson and Kendal Anderson, of Sutherland Conservation and Consulting, of Augusta, (all three had previously worked on parts of the applications for Waterville’s Main Street Historic District). They listed the building’s significance as architectural and its period of significance as 1965.

The architectural firm was James H. Ritchie and Associates, of Boston. The Sutherland group found that different members of the firm had initialed different parts of the 1963 plan, and that Ritchie had died in 1964.

The application explains that the building was “a good example of the Miesian school of Modernist architecture, applied to a health care facility in Maine.”

The “general characteristics of the Miesian style” that Ritchie and Associates used included “a recessed ground floor, use of concrete panels to express the building’s framing on the exterior, and the use of aluminum windows and a flat roof,” the application says.

The Miesian architectural style was a variant within the Modernist school that characterized skyscrapers and other large public buildings after World War II. It is named after Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969), a German architect who began his career in Germany and emigrated to the United States after Hitler rose to power.

After the war, a source cited in the application says, the United States government financed a large number of new hospitals. Hospital designers adopted the Modernist style because they found it functional and affordable.

When Seton Hospital opened, the Sutherland team wrote, it offered “over 150 beds…and the latest in medical technologies.” They quoted from a July 27, 1965, Waterville Morning Sentinel article that began, “All patients’ rooms are quiet, comfortable, pleasing to the eye, and designed to give an excellent view of the surrounding landscape.”

The article went on to talk about air conditioning in some areas (not the patients’ rooms); four modern elevators with telephones; the “spacious lobby” with a “modern coffee shop” and a “gift and stationery shop” nearby; and the “soft-lighted and beautifully designed” chapel, with seats for over 80 people. The laboratory was “ultra-modern,” the X-ray department had “the most modern equipment.”

The second floor was for obstetrics, and was partly air-conditioned. Other patients had the third, fourth and fifth floors. The sixth floor at first provided living space for members of the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, the organization that ran Seton Hospital, and later became additional patient space.

The Sisters’ quarters included 15 bedrooms; a kitchen and a laundry room; “a sewing room, guest room and parlor”; a dining room and community room separated by a folding panel, so they could be combined for a large group; “an office for the superior”; and the Sisters’ private chapel.

The Sisters of Charity came to Waterville in 1913, the Sutherland team explained, and in April took over the I. C. Libby Memorial Hospital, changing its name to Sisters Hospital. In 1923, they built a larger Sisters Hospital, on College Avenue. By 1963, that hospital had “an 86 percent occupancy on a year-round basis, and 107 percent occupancy at the height of occupancy,” necessitating the larger Chase Avenue building.

Dr. Frederick Charles Thayer served on the Sisters Hospital board until 1931, when he set up Thayer Hospital, first in his house on Main Street and later on North Main Street. Thayer and Seton merged in 1975 to become Mid-Maine Medical Center; in 1997 the Mid-Maine and Kennebec Valley health systems merged to form MaineGeneral.

The 2016 application describes the Seton Hospital building as “vacant.” Articles in the Central Maine Morning Sentinel in August 2022 described plans to convert most of the building to apartments, with leased storage space in the basement. Reporter Amy Calder wrote that because the former hospital is on the National Register of Historic Places, “construction must preserve the historic nature of the building.”

Main sources

Beard, Frank A., and Robert L. Bradley, National Register of Historic Places.

Inventory—Nomination Form Professional Building July 1981.

Beard, Frank A., and Stephen Kaplan, National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form Waterville Post Office, October 1976.

Corbett, Matthew, Scott Hanson and Kendal Anderson, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Elizabeth Ann Seton Hospital, Jan. 18, 2016.

Hanson, Scott, and Kendal Anderson National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Waterville Main Street Historic District (Boundary Increase), June 3, 2016.

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Now that fall is upon us, the American Red Cross is asking the public to start the season off with a lifesaving blood or platelet donation. While the leaves turn, the need for blood never changes. Those who give this fall play an important role in keeping the blood supply on track for patients counting on blood products for care – especially ahead of the busy holiday season. Book a time to give blood or platelets by using the Red Cross Blood Donor App, visiting RedCrossBlood.org or by calling 1-800-RED CROSS (1-800-733-2767).

Now that fall is upon us, the American Red Cross is asking the public to start the season off with a lifesaving blood or platelet donation. While the leaves turn, the need for blood never changes. Those who give this fall play an important role in keeping the blood supply on track for patients counting on blood products for care – especially ahead of the busy holiday season. Book a time to give blood or platelets by using the Red Cross Blood Donor App, visiting RedCrossBlood.org or by calling 1-800-RED CROSS (1-800-733-2767).