REVIEW POTPOURRI – Singers: Henry Burr & Alice Nielsen; TV Series: Marcella

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates

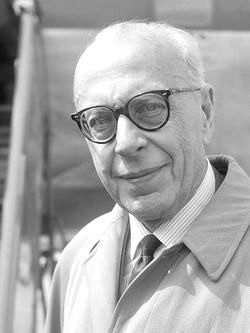

Henry Burr

Over Yonder Where the Lilies Grow/Hugh Donovan – The Rose of No Man’s Land; Columbia A2670; ten inch acoustic 78, recorded October, 1918.

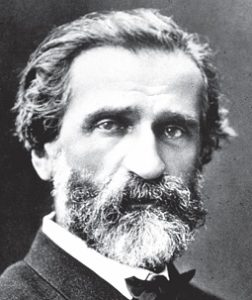

I have written before about Harry McClaskey (1882-1941), alias Henry Burr, who recorded prolifically 100 and more years ago, while another singer Charles Harrison (1878-1965) alias Hugh Donovan is featured on side 2 of the above, very old record. The two songs were written out of different aspects of World War I from 1914-1918, also known erroneously as The War to End All Wars, and make this record a document of some historical interest.

Over Yonder Where the Lilies Grow is akin to the more famous war poem, In Flander’s Fields, a region of Belgium where two different Battles of Ypres were fought and much loss of life occurred on both sides. The song’s lyrics evoke sadness in the first three lines – ‘Last night I lay a-sleeping a vision came to me/I saw a baby in Flander’s maybe/It’s eyes were wet with tears’, etc. The song mentions the lily of France/Fleur de-Lis and ‘the land of long ago’.

The Rose of No Man’s Land pays tribute to the Red Cross nurses who risked their lives helping the wounded in often makeshift, dangerous settings. ‘It’s the one red rose the soldier knows/It’s the work of the master’s hand/It’s the sweet word from the Red Cross nurse/She’s the rose of no-man’s land.’

Both tenors did very good work here; the tunes were sticky sweet pleasant.

Charles Harrison studied with a New York City voice teacher Frederick Bristol (1839-1932) who operated a summer music camp in Harrison, Maine.

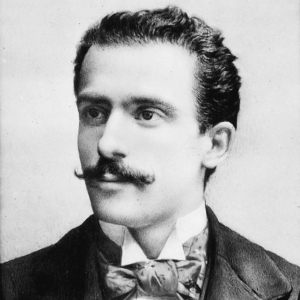

Alice Nielsen

By the Waters of Minnetonka/From the Land of Sky Blue Water; Columbia A1732; ten inch acoustic disc, recorded February, 1915.

Soprano Alice Nielsen (1872-1943) scored huge success on the opera and vaudeville stage with her appearances in Boston, New York City, London and Italy. She recorded opera arias, operettas, popular tunes and hymns. One megahit was a shellac of Home Sweet Home.

The above two selections were popularized by many other singers in concert, on the radio and via records. And, like Charles Harrison, she too studied with Frederick Bristol. By another coincidence, she had a summer home in Harrison, Maine, which later became a dancing school.

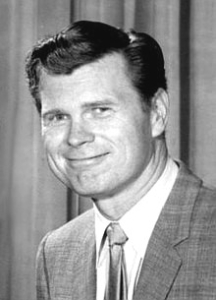

Marcella

The Netflix suspense series, Marcella, has Anna Friel portraying a London detective and giving one of the most powerfully sustained performances over the series 24 episodes that I have seen from anybody. Highly recommended.