REVIEW POTPOURRI: Placido Domingo, Dean Martin, Gene Krupa

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates

Miscellany!

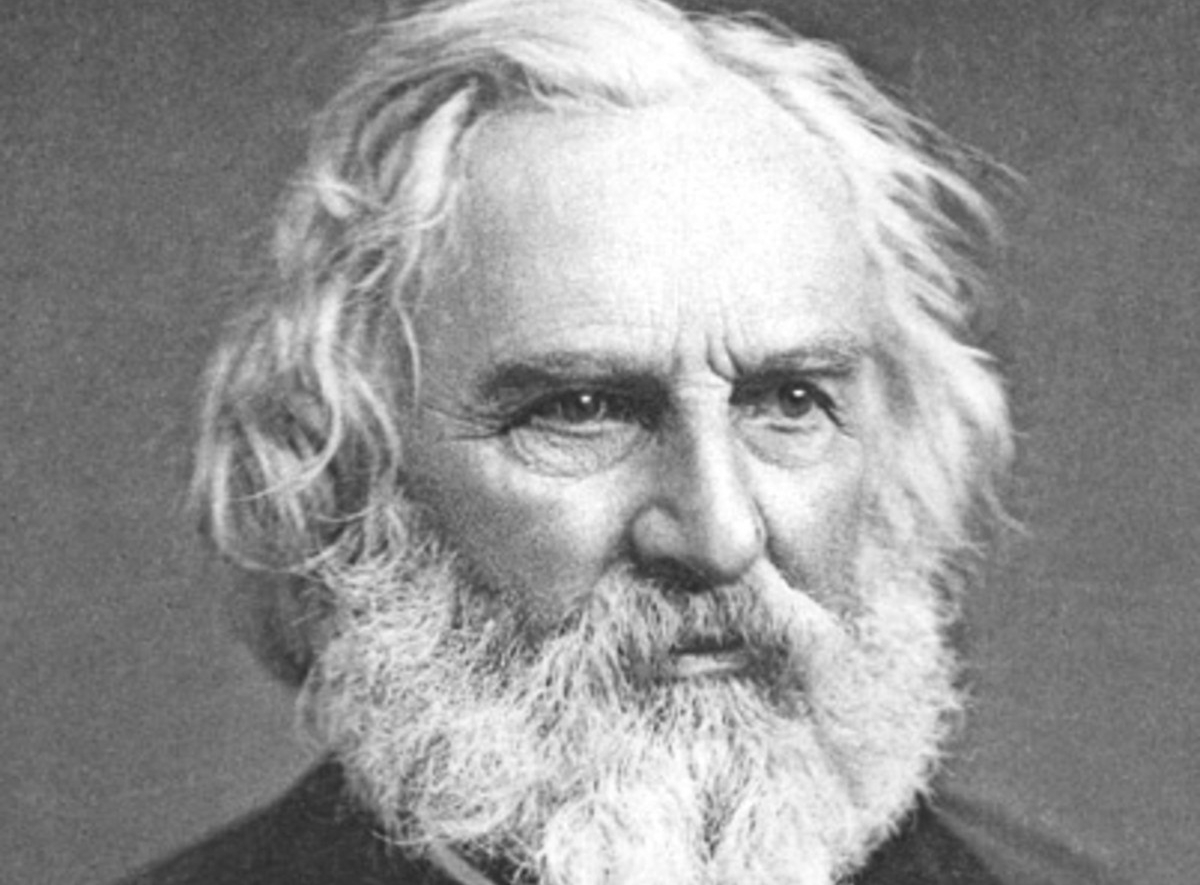

Placido Domingo

Opera singer Placido Domingo, who’s 79, has tested positive for coronavirus. We can all hope he will be fine, as people even older are recovering from this. But we need to continue with the suggested safety steps, too.

While on the subject of Domingo, I have some of his recordings – various complete operas, single arias, and three tenors collaborations with Pavarotti and Carreras. He also has had a long, professional singing career and seems to have paced himself, as opposed to some singers who ruin their voices earlier. His Cavaradossi on the Leontyne Price Puccini’s Tosca set conducted by Zubin Mehta is a good introduction to his artistry.

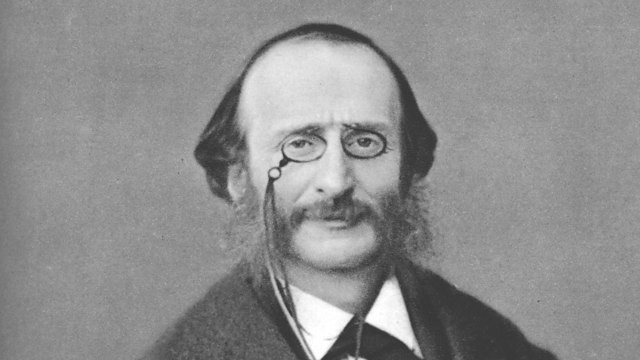

Dean Martin

Dream with Dean

Reprise LP, August 1964 release.

Dean Martin was a singer of talent, even if not on the same level as Frank Sinatra. He phrased with intelligence, suavity and an astute sense of timing.

This album featured him in a small jazz combo setting, accompanied by four very fine instrumentalists – guitarist Barney Kessel, pianist Ken Lane, bassist Red Mitchell and drummer Irv Cottler. Dino sang such staples as My Melancholy Baby, Fools Rush In, I’ll Buy That Dream and a scaled down, subdued Everybody Loves Somebody plus eight additional selections. And it can be heard on YouTube.

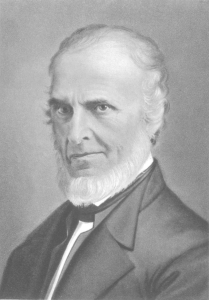

Gene Krupa and His Orchestra

It’s Just a Matter of Opinion; That’s My Home

Columbia, 37067, ten-inch 78, recorded mid-1940s.

Gene Krupa (1909-1973) was a truly gifted musician on the drums who expanded their boundaries from mere rhythm to outstanding artistic virtuosity on the 1930’s hit recording, Sing Sing Sing, by Benny Goodman’s orchestra. At various times during the ‘40s and ‘50s, Krupa led his own orchestra and recorded a number of 78s for Columbia Records.

Both sides feature the very good jazz singer, Buddy Stewart (1922-1950), who is joined in It’s Just a Matter… by Carolyn Grey, who was heard often during the big band days. The songs are not well-known staples but they are quality listening in their vocal and instrumental arrangements.

Krupa played frequent battles of the drums with friend Buddy Rich in concert and recording. He also struggled with heroin addiction but overcame it. Buddy Stewart was killed in a car accident at 27 while on a road trip to New Mexico to be with his wife and child. Carolyn Grey is still living at 98.