Up and Down the Kennebec Valley: Education in Vassalboro & Sidney

by Mary Grow

by Mary Grow

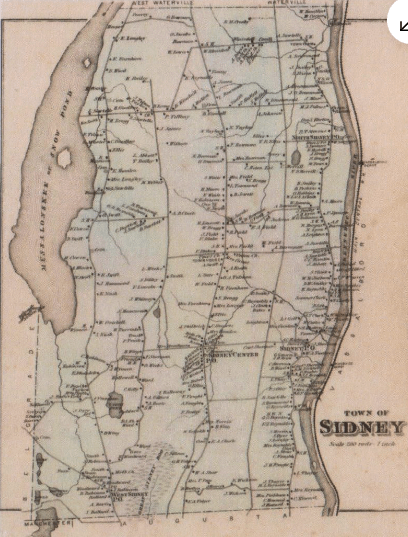

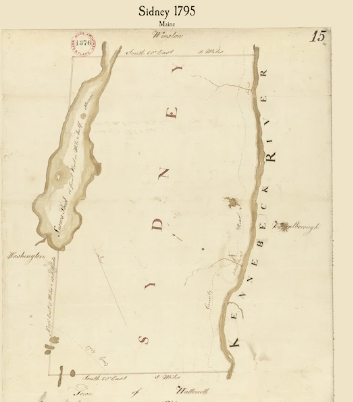

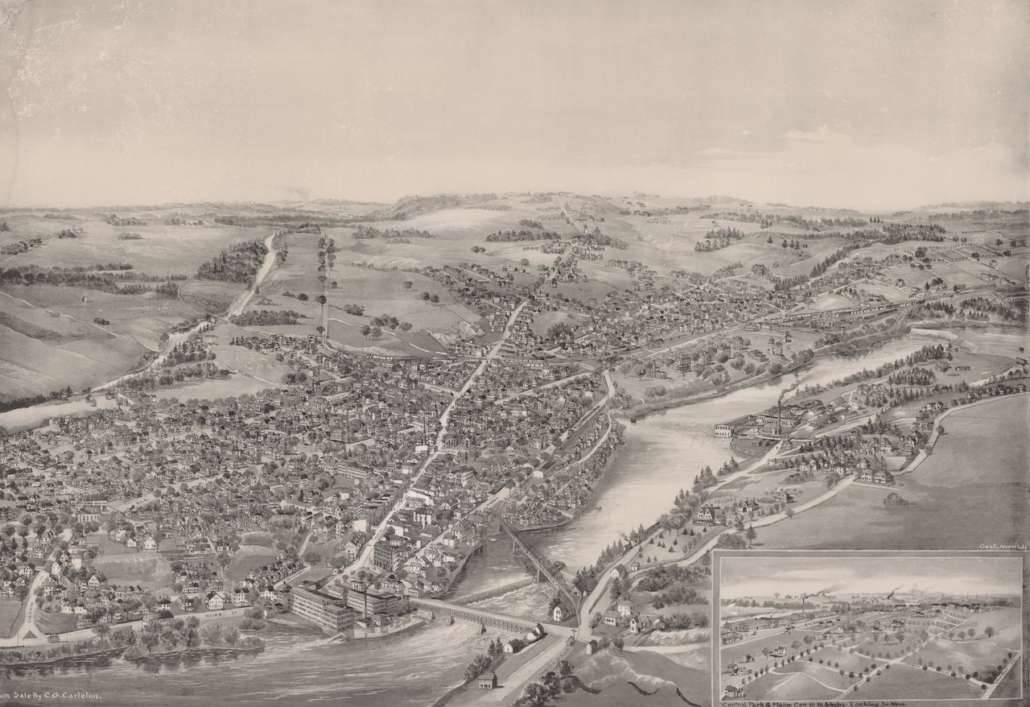

Another Kennebec Valley town incorporated April 26, 1771, simultaneously with Hallowell (then including Augusta), was Vassalboro, then including Sidney. Vassalboro’s and Sidney’s early educational systems will therefore be examined next.

According to Alma Pierce Robbins’ 1971 history of Vassalboro, voters did not discuss education at their first town meeting, held May 22, 1771. At a Sept. 9 meeting, they approved money to support a minister, but not a schoolmaster.

The next education discussion Robbins reported (but not its outcome) was in 1785, after the October report of the Portland convention discussing separation from Massachusetts had called on towns to fund public schools. At town meetings thereafter, no matter how frequent, she said “much discussion was devoted to ‘Schooling.'”

Until the separation of Sidney in 1792, Vassalboro voters needed to educate students in both parts of a town divided by the unbridged Kennebec River running through the middle.

Robbins reported a committee set up 13 school districts in 1787. In 1788, voters appropriated 70 pounds for schools. At a 1789 town meeting, District 5 was created on the west side of the river. There was also a District 5 on the east side, according to Robbins and to Henry Kingsbury, in his 1892 Kennebec County history.

Kingsbury apparently overlooked the early records Robbins found. He said about Vassalboro schools, “The first record of anything pertaining to this important element of civilization was made in annual meeting of March 1790, when the town east of the river was divided into districts, and an earnest support of the public schools commenced.”

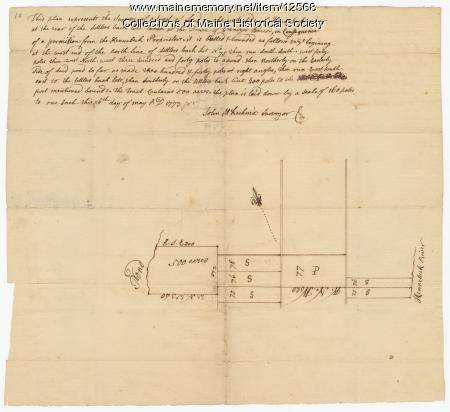

He and Robbins said districts one through five went north to south on the east side of the Kennebec, including the first and second miles from the river and, for districts two and three, part or all of the third mile. Districts six through nine ran to the east town line, with districts six and seven including the fourth and fifth miles and eight and nine the third, fourth and fifth miles.

Divisions between districts were by lot lines. District one went from the north town boundary south to Jacob Taber’s lot; district two from Taber’s south to Jonathan Low’s; and so on.

Kingsbury named the six men on the 1790 committee that determined the district lines and continued, “Teachers were hired and the schools of the town commenced.”

District boundaries were redrawn “as the convenience of the inhabitants demanded,” Kingsbury said. Any west of the Kennebec disappeared after Sidney became a separate town on Jan. 30, 1792.

In 1795, Kingsbury wrote, another southern Vassalboro district was formed, and “a committee was chosen in open town meeting to obtain teachers for all districts and pay out the moneys according to the number of pupils in each.”

In 1797, he said, “the number of schools [and presumably of districts] was reduced to seven,” and Vassalboro selectmen paid out the $700 voters appropriated and hired the teachers. That was the year Robbins said voters authorized “the school in the middle west section of town” to hold classes in the town house, suggesting not every district had a schoolhouse.

Kingsbury said districts were redivided in 1798. In 1799, voters raised $1,000 “to build ten school houses.” Robbins said there were 10 districts in 1798, 11 in 1800.

By 1806, there were enough members of the Society of Friends, or Quakers, in Vassalboro so their students in District 7 were separated into their own district (as had been done in Sidney in 1799 – see below). Robbins quoted an 1809 town meeting vote: “there shall be two schools kept by a woman in summer and the Friends shall have the privilege of choosing one mistress, and there shall be a master in winter.”

In 1816 and for some time afterwards, Kingsbury wrote, a town-appointed committee reviewed the then-17 schools, a system that produced “beneficial results.” After 1810 and 1823 rearrangements, in 1839 Vassalboro was divided into the 22 school districts that he said remained “substantially the same” in 1892.

Robbins disagreed. She wrote that the school committee’s 1839 22-district plan “was of little value,” because the next year there was a rearrangement and creation of a 23rd district. Vassalboro had 23 districts “much of the time” until state law eliminated district schools, she said.

Administration was also changed; Kingsbury gave no dates. The (1816?) town committee that inspected schools and hired teachers was replaced by “a proper person” in each district, and in “later years” – and still in 1892 – by an elected town superintendent.

Robbins cited deficiencies listed in school reports and town meeting minutes. Students were truant; parents lacked interest; poorly paid teachers were expected not only to teach, but to keep the woodstove going and the classroom clean and, under a late-1840s regulation “to look after the scholars while in school and on the way home.”

Around 1850, teachers were paid $2 a week, Robbins wrote. She added, “Little wonder that several schools ‘closed suddenly’.”

Buildings were often badly maintained. An 1865 school committee report described students “shivering with the cold, their heads in close contact with the stove funnel, inhaling death with every inspiration.” An 1870 report referred to “the miserable affairs called school houses.”

As of 1870, Robbins said, state law defined school terms: the summer term was 9 and 3/17 weeks, the winter term was 10 and 13/14 weeks. (She did not explain how weeks were divided into 14ths and 17ths.)

Robbins found that Vassalboro had 1,200 school-age children in 1850. In 1892-1893, the number was down to 636; 20 schools were open, most with fewer than 20 students, one with six.

* * * * * *

The earliest Vassalboro high school was Vassalboro (or Vassalborough) Academy at Getchell’s Corner, in northwestern Vassalboro, opened in 1835, closed before 1868. Miss Howard’s School for Young Ladies opened in 1837 at Getchell’s Corner. Robbins cited no evidence of a long life for that institution.

Oak Grove Seminary, on Riverside Drive at the Oak Grove Road intersection, was started by area Quakers in 1848 or 1850. (For more information on Vassalboro high schools, see the July 22, 2021, and Oct. 14, 2021, issues of “The Town Line”.)

In 1873, Robbins said, state law required high schools. Vassalboro opened one in East Vassalboro and one at Riverside, and North Vassalboro residents “after a few sharp discussions erected a new and commodious house at a trifle over six thousand dollars.”

Kingsbury said voters appropriated $500 for the East Vassalboro high school, in a building on the west side of Main Street nearly opposite the Vassalboro Grange Hall. By 1892, he wrote, “the continued success of Oak Grove Seminary has superseded the necessity for the high school.”

In 1892, Vassalboro’s schoolhouses were “in good condition,” Kingsbury said, with the 1872 North Vassalboro building the best. It had “three departments, and a large public hall on the second floor.” (This building still stands, privately owned in 2024.)

* * * * * *

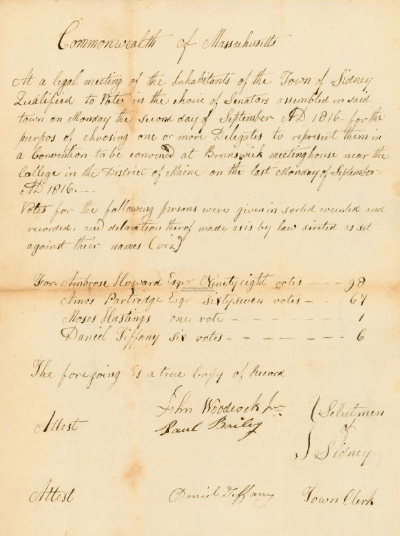

Alice Hammond wrote in her 1992 history of Sidney that in April 1792, less than three months after Sidney became a separate town, voters at a “school meeting” defined 10 school districts and named 10 “school collectors” (she did not describe their duties).

Voters also appropriated 100 pounds for “annual support of the schools.” A January 1794 special town meeting rescinded the appropriation; voters at the 1794 annual town meeting approved 50 pounds, and raised it to 60 pounds before the meeting ended.

Sidney’s school districts one through four ran south to north along the Kennebec, including the first and second miles from the river. District 1 went from the boundary with Augusta to Daniel Townsend’s south line; District 2 went upriver to Elihu Getchell’s lot; District 3 upriver to Hezekiah Hoxie’s north line; and District 4 upriver to the north boundary with Waterville (then still Winslow).

District five began at the northern end of “the Pond” (Messalonskee Lake); five through eight ran to the south town line, encompassing the third and fourth ranges, except for district seven.

District seven was in only the fourth range. District nine seems to have covered the third range in that area, as well as specifically “including Matthew Lincoln and Jethro Weeks in said district.”

District ten encompassed “all the inhabitants and land belonging to the said town on the west side of the aforesaid pond.” Belgrade annexed District 10 in 1799.

Also in 1799, Hammond wrote, voters gave Sidney’s Society of Friends in District 9, and nearby residents who were not Friends, their own district, number 11; and gave them their share of school funds to “lay…out in the manner they see fit.”

She added that a resident named Silas Hoxie (Hoxie was a common Quaker name) “requested unsuccessfully that he be given his share of the school money to ‘spend as he saw fit.'”

Hammond said Sidney had 19 school districts in 1848; but population declined thereafter. Kingsbury wrote that by 1891, districts had been reduced to 14, because there were fewer students – that year, he said, 333 students “drew public money.”

Hammond gave a financial example from District 9 (Bacon’s Corner) in 1843-44: total expenditure, $76.50, of which $24 went to a “Female teacher for 16 weeks of summer school” and $31.50 to a “Male teacher for seven weeks of winter school.” Seth Robinson contributed summer board; winter board cost $9.31.

The rest of the money went for building maintenance and supplies (including eight cents for a broom). Hammond added, “Having raised $77.50, the district ended the school year with a balance of $1.00.”

Referring to state laws requiring towns to raise a specified amount per inhabitant for school costs, Hammond said not until 1867 did Sidney voters agree “to raise what is required by law.” The requirement was 75 cents per resident that year; in 1868 the legislature raised it to one dollar.

Even after direct state aid started, Hammond said, “funding was inadequate and teachers’ wages were low.” In the later 1880s, she wrote, per-student expenditure was $5.63 annually. Summer term teachers averaged $3.59 a week; winter term teachers got $4.68 a week plus $1.46 a week for board.

Hammond wrote that in the 1870s, “responsibility for governing the school began to move from the individual district to the town.” Town school committees were elected and charged with hiring teachers, and “some level of standardization began to exist,” like common schedules and textbooks.

Kingsbury, in his chapter on Sidney, for an unexplained reason began discussion of education with the fiscal year ending Feb. 10, 1892. For that year, he said, town voters appropriated $1,500 for schools (plus $2,000 for roads; $1,200 “to defray town charges”; $25 for Memorial Day; and another $25 for “town fair” [the annual Agricultural Fair, started by Grange members in 1785]).

In 1892, Kingsbury wrote, “The town voted to change from the district to the town system” for managing schools; Hammond wrote that the Sidney school committee was made responsible “for all the schools in the town.” She added that the school term was set town-wide at 21 weeks that year (increased to 25 weeks a year in less than a decade), and the first school superintendent was hired.

Town-wide organization promoted school consolidation, and fewer schools created a need for transportation. Hammond wrote that “many” educators thought it was good for students to walk four or five miles to school; but many parents thought any child living more than a mile and a half from a school should have transportation, “and this was the [undated] decision of the [Sidney] school committee.”

* * * * * *

Your writer has found no information on a 19th-century high school in Sidney.

Main sources:

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992)

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971)

Websites, miscellaneous.