Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Rufus Matthew Jones — Part 2

by Mary Grow

Part of Rufus Matthew Jones’ story of his early life, in his 1921 book titled A Small-Town Boy, was summarized last week. This week’s article continues his story, starting with his primary schooling in one-room schoolhouses in South China and Weeks Mills.

Jones wrote that he was “four years and six months old” when he first walked with his older sister the quarter-mile to the South China schoolhouse, just south of the four corners. He was starting at the beginning of the 1867 summer term; only younger students attended, because “the big boys” were doing farm work.

The woman teacher taught all ages and all subjects. After the morning prayer, Scripture reading and hymn, she called the grade levels one at a time to the blackboard at the front of the room to begin lessons.

Winter sessions, Jones wrote, were different. The back two or three rows of seats were occupied by “big boys and girls,” and discipline was a problem. Teachers were likely to be men, on the theory that muscle mattered – though he promptly cited a woman who maintained excellent order and a man who provided “a fine illustration of educational chaos.”

The latter, he said, was physically removed from the schoolhouse by some of the unruly older boys. His successor, a physically smaller man, quickly established moral authority over the students and led a successful session.

These schools had books, blackboards and chalk, but little else of supplies or equipment. Jones wrote of learning geography without maps or a globe, and physics and physiology without equipment or experiments.

Jones claimed that he learned the first three letters of the alphabet on his first day of school – “the most momentous intellectual step I have every taken.” He marveled that “all of Shakespeare’s plays, the whole of the English Bible, Browning’s Ring and the Book, and everything else I have ever read are made up of those letters I learned in that Primer Class!”

At 15, Jones walked three miles each way to the Weeks Mills one-room school, because the teacher there was outstanding. The next fall he began 11 weeks at Oak Grove Seminary, in Vassalboro.

He was one of the boarding students, sharing a dormitory room with another boy. Fathers took turns bringing them home for weekends, and mothers supplied a week’s worth of food, which the students ate cold or cooked – boiled eggs, for instance – in their rooms.

At Oak Grove, Jones began learning Latin – by the end of his college education he was proficient in Latin and Greek – and studied astronomy under an excellent female teacher. Even at Oak Grove, there was “no telescope, no observatory, no proper instruments,” but he learned enough to skip astronomy in college, earning a 95 on the exam without taking the course.

In the spring of 1879, Jones wrote, he and his father were planting potatoes together when he informed his father that he wanted to go to the Moses Brown Friends School, in Providence, Rhode Island. The family had no money for the undertaking; Jones was awarded a scholarship that covered a year’s tuition and board.

Another chapter in A Small-Town Boy deals with his informal leadership of a group of boys about his age, especially their outdoor lives. He summarized: “We were absolutely at home on the water, in the water, on the ice or through the ice, in the woods, or in the snow.”

One exciting episode he recounted involved out-of-town pirates net-fishing surreptitiously in China Lake. He and his gang assembled a fleet of rowboats, equipped themselves with grapnels and “revolvers and old muskets” and went in search of the invaders.

In the north end of the east basin, they found two men who had stretched nets from the northernmost island to each shore. The men hauled in their nets and made for shore, chased by the boys shooting “in the air or on the water where we were sure not to hit them.”

The boys caught up as the men reached land and scared them into promising never to return.

Jones wrote about two others of the five China Lake islands that he and his friends frequented as teenagers. Round or Birch Island, in the east basin, was a place for a corn roast and perhaps an overnight camp-out. The amusement park on Bradley’s Island, in the west basin, included a bowling alley.

A Small-Town Boy has brief verbal portraits of some of the Jones’ neighbors, identified by first names only. One was a shy, quiet man “who gave the impression of being very stern and grouchy.” When his mowing machine tipped over and trapped him, Jones wrote that the only thing he said to the neighbor who lifted the machine off him was “That’s all I need of thee.”

This man, Jones said, was secretly “one of the tenderest-hearted persons in the town.” He heard that a neighbor with a sick wife was low on firewood: he left a load of stovewood in the dooryard one night. He heard another family was out of butter: he left them a can of milk with “a four pound chunk of butter” floating in it.

Another neighbor made a hole in the gable of his barn so barn-swallows could come and go, and let Jones and his friends – and birds – eat the cherries from his two cherry trees. Yet another, when his seasonal farm chores were finished, hurried to help any neighbor who was behind schedule with planting, haying or some other job.

Jones mentioned one ungenerous neighbor. The example he related said this man sold some hens to a buyer in the far end of town, and on the journey, some of the hens laid eggs. Seller and buyer argued “for a long period” over who owned the eggs.

Jones had written an earlier book about his boyhood. A Boy’s Religion from Memory was published in 1902, and as the title says, focused more on his religious and spiritual life than on his small-town surroundings.

The Trail books begin with Finding the Trail of Life (1926), which partly repeats and expands on A Boy’s Religion. It was followed by The Trail of Life in College (1929) and The Trail of Life in the Middle Years (1934).

These books contain a mix of Jones’ outer life, as he attended high school and college and began his career, and his inner life, as life-altering decisions were shaped and carried out primarily according to the inner voice or inner light that Quakers take as their guide.

From the Friends School, he went to Haverford College, in Haverford, Pennsylvania, outside Philadelphia. Founded by Friends in 1833, it had been accepting non-Quakers since 1849, but did not admit its first women until 1969 (as transfer students; full acceptance dates from 1980).

Jones wrote in The Trail of Life in College that he enrolled as a sophomore in the fall of 1882. Studying Latin and Greek, philosophy and mathematics, he did extra work and took advanced classes. By the end of junior year he needed “only a few hours per week” for another year to earn his bachelor’s degree.

He therefore arranged to write a master’s thesis the same year, 1884-1885, and earned both degrees. The thesis was on American history; but, he wrote, it was his graduation essay on mysticism that was more influential in his later writings.

Returning to the South China family farm, Jones received two offers in two days: a graduate fellowship in history at the University of Pennsylvania, and a one-year teaching position at Oakwood Seminary, described as a Quaker boarding school, in Union Springs, New York.

With the guidance of Aunt Peace (mentioned last week as a powerful influence) and the inner light on which he so often relied, Jones chose teaching – a decision he said he never regretted.

His career kept him away from China, except for vacations, for most of the rest of his life. He taught for two years at Moses Brown School, in Providence. In 1889, he was considering graduate work at Harvard when he was invited to become principal of Oak Grove Seminary in neighboring Vassalboro.

He served four years, 1889-1993, with younger brother Herbert as business manager. In later autobiographical works, he wrote about how much he gained in the Oak Grove community, in leadership skills, problem-solving and friendships.

In 1893 he again planned graduate work at Harvard. This time he was distracted when “the call came to me” to teach philosophy at Haverford and edit the Friends’ Review (later The American Friend).

He took the train from Vassalboro, “leaving my beloved Oak Grove Seminary for the last time with my face wet with quiet tears,” and stayed at Haverford until retiring in 1934. The Find a Grave website says he earned a master’s degree from Harvard in 1901.

Jones traveled in Europe for pleasure as a young man, and later on major errands as a leader among American Friends, especially during the world wars. He was among organizers of the American Friends Service Committee in 1917, and worked for the organization the rest of his life. One AFSC mission in which he participated was an unsuccessful 1938 attempt to talk peace with Adolf Hitler.

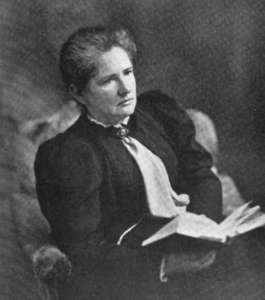

In the summer of 1888, Jones married his first wife, Sarah Hawkeshurst Coutant, of Ardonia, New York, whom he met at Oakwood. It was she who encouraged him to take the Oak Grove job in 1889. Their much-loved son, Lowell Coutant Jones, was born there Jan. 23, 1892. Sarah died of tuberculosis in 1899; Lowell died of diphtheria in 1903.

In 1902 Jones married for the second time, to Elizabeth Bartram Cadbury (Aug. 15, 1871 – Oct. 26, 1952). Their only child, Mary Hoxie Jones, was born July 27, 1904.

Family summer vacations were often spent at Pendle Hill, a simple wooden house on the west side of Route 202 in China, overlooking China Lake. Jones and his brother Herbert “cut trees for lumber and designed the house” during the 1915 Christmas vacation, according to the China bicentennial history.

Other sources say a local carpenter did the building the following spring, badly enough so that the Jones brothers did extensive follow-up work. Also on the property was a log cabin that Rufus Jones reportedly built himself.

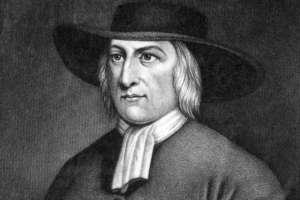

Jones named the house Pendle Hill (your writer assumes after Pendle Hill, in England, where Quaker founder George Fox had a revelation in 1652). Pendle Hill was added to the National Register of Historic Places on Aug. 4, 1983, at the same time as the Pond Meeting House, on Route 202, and the Abel Jones house, in South China.

Jones died in Haverford on June 16, 1948. His widow died Oct. 26, 1952. Both are buried in a Haverford Friends cemetery.

Main sources

Jones, Rufus M., A Small-Town Boy (1941).

Jones, Rufus M., Finding the Trail of Life (1926).

Jones, Rufus M., The Trail of Life in College (1929).

Websites, miscellaneous.