From left-to-right: Gold, Pyrite and Tin Ore.

Previous articles have talked about some of the natural resources in the central Kennebec Valley, notably clay and granite. Renewables, like timber, fur-bearing and other game animals and fish, have been ignored – would an enterprising reader like to tackle one or more of those topics?

This piece will cover a varied assortment of other resources. As with those discussed before, information from local histories is scanty.

* * * * * *

Gold is unusual in Maine but not completely lacking. The Maine Geological Survey has on its website a list of streams, all but one in Franklin, Oxford or Somerset county, worth panning for gold. (The outlier is the St. Croix River, separating the United States and Canada; gold has been found in Baileyville, in Washington County.)

Locally, there might have been gold in the Albion-Benton area. One of the personal paragraphs in Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history is about Augustine Crosby (1838 – 1898).

Born in Albion, son of Luther and Ethelinda Crosby and grandson of Robert and Abigail Crosby, Augustine spent 10 of his early years in Massachusetts; came back to Benton and went into lumbering; served in the Civil War (as did his father) and as of 1892 was in “the South” building sawmills.

While in Benton, Crosby married Asher Crosby Hinds’ daughter, Susan A. Hinds. And, Kingsbury wrote, “He invented a dredge for gold dredging and spent some time operating it.”

According to a Crosby family diary found online, Augustine fell ill in September 1898 and died Sept. 28. He was buried Sept. 30 in what the diarist wrote “was called Smiley burying ground.” The funeral was well attended, with 23 teams, the diarist believed, following the hearse. His wife survived him; the diarist mentioned several times her visits to and sympathy for Sue.

(See the website called Winslow Maine Crosby Diary for additional excerpts. The diarist was Elizabeth B. Hinds Crosby (1892-1912); the hand-written diary was transcribed by Clyde Spaulding, her great-grandson.)

(Asher Crosby Hinds [1863-1919] was a Benton native and Colby College graduate, Class of 1883. After newspaper work in Portland, in 1889 he got a position as clerk to the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. He served in clerkship positions until 1911, editing the Rules, Manual, and Digest of the House of Representatives [1899] and Hinds’ Precedents of the House of Representatives [1908]. In 1911 he was elected to the first of three terms as a Republican Representative from Maine. He died in Washington, D.C., and is buried in Portland’s Evergreen Cemetery.)

In China, Indian Island (previously Round Island or Birch Island) in the east basin of China Lake was reported – inaccurately, it appears — to have gold deposits. Several sources cite prominent Quaker Rufus Jones’ memoir of his boyhood, in which he wrote that people dug over the whole island and found only pyrite, an iron sulphide often called “fool’s gold” because it is yellowish.

One more hint of local gold is found in Milton E. Dowe’s Palermo Maine Things That I Remember in 1996. Dowe wrote: “It’s known that there was a gold mine east of the Marden Hill Road [in north central Palermo]. I have been there to the site but never heard the facts of it.”

* * * * * *

Tin, described by Wikipedia as “a soft, silvery white metal with a bluish tinge,” that does not occur as “the native element” but has to be extracted from other ores, is another resource Kingsbury mentioned.

Mixing tin with copper creates bronze, as people discovered some 3,000 years B.C. Wikipedia does not list the United States as a source of tin. But Kingsbury related a story about tin in Winslow, Maine.

As he told it, about 1870 Charles Chipman noticed “[i]ndications of tin ore” in the rocks along a brook on J. H. Chaffee’s property. He and others, including Thomas Lang (a prominent citizen of Vassalboro) and a doctor from Boston, concluded it might be worth mining.

They organized a company and dug more than a hundred feet down, finding more tin as the shaft went lower, but not enough to cover costs, never mind make a profit. Kingsbury wrote that they gave up around 1882.

* * * * * *

One rather unusual resource is a mineral spring. Mineral springs are similar to ordinary springs, areas (often hillsides) where groundwater naturally comes to the surface because the ground slopes below the water table.

Wikipedia says a mineral spring contains dissolved minerals, especially salt, lime, lithium, iron and sulfur compounds, and sometimes harmful components like arsenic.

For generations people have believed some mineral springs are healthful. “Taking the cure” or “taking the waters” was popular, especially in 18th and 19th century Europe for upper-class Europeans and Americans. Spas have been developed around mineral springs as destinations for people seeking better health; Wikipedia’s illustrations include mineral spas in Europe, India and Iran.

Major mineral springs that have been developed in Maine include Blue Hill Mineral Spring near Blue Hill, in Hancock County, and especially Poland Spring, in Poland.

The spring in Blue Hill was “well-known” before a company was organized in 1888 to exploit its supposed healing properties, according to the Maine Memory Network. Blue Hill’s mineral water was sold nation-wide, including being available on Pullman cars on many eastern railroads. The company folded after a November 1915 fire destroyed its processing buildings.

In 2014, three former University of Maine professors wrote a short article on two mineral springs in Baxter State Park that contained potassium and sodium and served as salt licks for deer and moose.

Poland Spring, in Poland, is by far the best-known Maine spring. According to Wikipedia, the spring is on the lot where Jabez Ricker opened an inn in 1797. In 1844, Jabez’s grandson, Hiram Ricker, said drinking water from the spring had cured his chronic indigestion.

The inn was enlarged, more guests heard about the alleged properties of the water and the Rickers started bottling and selling it. The elaborate Poland Spring House opened in 1886.

There is still a hotel at the spring, Poland Spring Resort. Bottled water now sold under the Poland Spring label comes from more than one part of Maine.

Locally, there are records of mineral springs in Augusta and China.

James North wrote in his Augusta history that in 1810 there were two prominent mineral springs in the area. The Togus Mineral Spring, also called the Gunpowder Spring (North did not explain why) in Chelsea had become well-known as the enthusiasm for mineral waters spread. It was in a meadow; its water had been compared to water from a similar spring in Bowdoin.

Wikipedia adds that the name “Togus” probably came from a Native American word, worromontogus, which can be translated as “place of the mineral spring.” In 1858, a granite dealer from Rockland built the Togus Spring Hotel, with “a stable, large pool, bathing house, race track, and bowling alley.” The venture was unprofitable, and in 1866 the United States government bought the building for a veterans’ home.

According to North, a newly discovered spring in downtown Augusta, close to the Kennebec, was even more popular in 1810 than the Togus spring. He described the location by naming the owner of a nearby house that was on Water Street “opposite Laurel Street,” information that puts the mineral spring in the northern end of the business district, north of the Calumet bridge.

The mineral spring in China, according to local historian Clinton Thurlow, was northwest of South China village, on the west side of China Lake’s east basin. In one of his histories of the Wiscasset, Waterville and Farmington narrow-gauge railroad, Thurlow provided information on the branch line from Weeks Mills to Winslow that ran trains for a few years, beginning on July 9, 1902 (the tracks were removed about 1915, he wrote).

There was a dance pavilion in South China then, on the western edge of the village, and Thurlow wrote that the railroad would run excursions from Winslow to South China, taking passengers to the pavilion early in the evening and bringing them back to Winslow around midnight.

There was another popular place on the WW&F line to Winslow, not far north of the pavilion. Thurlow wrote: “A mineral spring between the Pavilion and Clark’s Crossing provided the occasion for many an unscheduled stop while train crews and passengers alike refreshed themselves.”

Clark’s Crossing was presumably the place where the tracks crossed the still-existing Clark Road that runs toward China Lake from what is now Route 32 North (Vassalboro Road). Your writer has found no other reference to this spring, but does not doubt its existence, because Thurlow talked with several former WW&F employees.

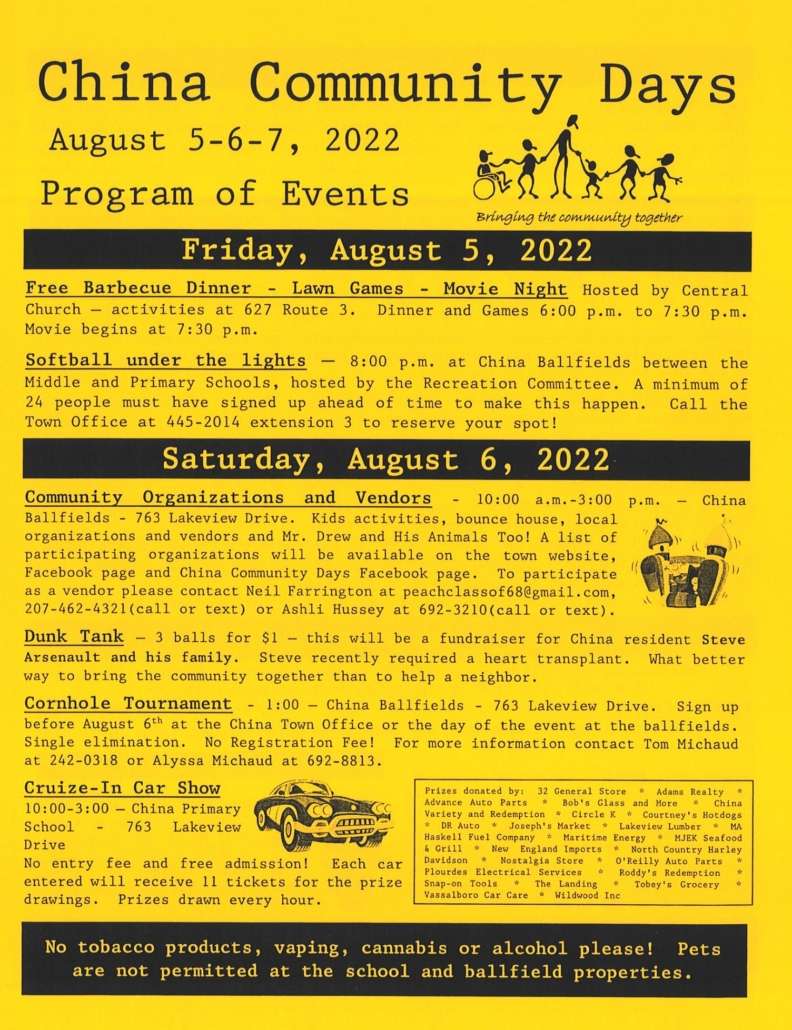

Update on Victor Grange

Victor Grange

Victor Grange #49, in Fairfield Center, organized in 1874, first was profiled in this series on May 13, 2021. This year’s July 14 issue of The Town Line reported that Grange members were about to have the hardwood floors downstairs refinished, probably for the first time since the building opened in 1903.

Grange Lecturer Barbara Bailey reported on July 31 that the floors are done! Grange members intended to spend the first day of August cleaning up dust from the sanding and washing windows before they rehung curtains.

Wednesday, Aug. 3, is the scheduled day to move furniture – including two pianos – back in.

Bailey invites anyone interested in this building preservation and restoration work to contact her at 453-9476 or email baileybarb196@gmail.com. The Grange email address is victorgrange49@gmail.com.

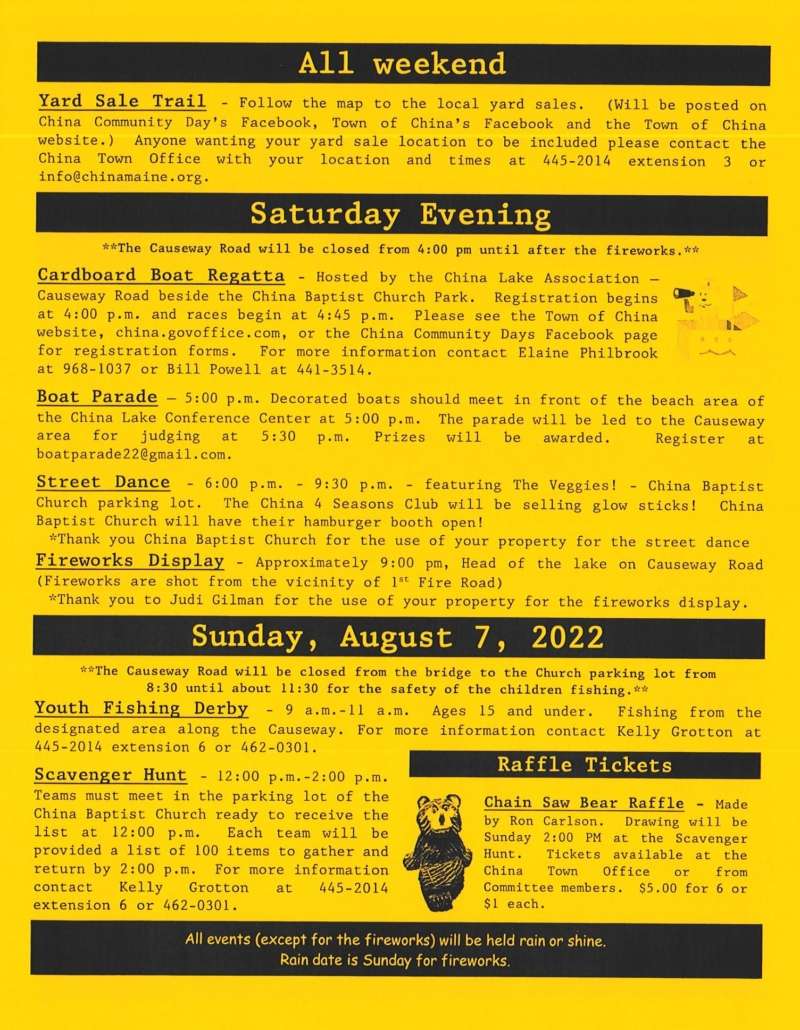

Update on the July21 update on the Kennebec Arsenal

Kennebec Arsenal

Augusta’s Kennebec Arsenal, a group of eight granite buildings dating from 1828-1838 and designated a National Historic Landmark District, has been discussed in two earlier articles in this series, in the Jan. 21, 2021, and Feb. 10, 2022, issues of The Town Line. The buildings have been privately owned since 2007; when the owner bought them from the state, he agreed to keep them in repair and maintain their historic value.

This writer’s July 21 update, citing a story by Keith Edwards of the Kennebec Journal, reported that the Augusta City Council was considering declaring the property dangerous. A declaration would let councilors have repairs made and bill the owner, or have the buildings demolished.

The council postponed a decision until its July 28 meeting, Edwards wrote. In the July 29 Kennebec Journal, he reported that after almost four hours of discussion, councilors again delayed a decision. They plan to continue the hearing at their next meeting, scheduled for Aug. 4, at 5:30 p.m.

Edwards wrote that Augusta Codes Enforcement Officer Rob Overton told council members the buildings were in deplorable condition inside and out. He estimated the cost of making them usable again at around $30 million.

The owner, accompanied by his lawyer, pointed out that he had reroofed all the buildings – Overton had exempted the roofs from his criticism – and made other repairs. He said he intends to ask for local permits to renovate five buildings by the end of August, planning to complete the work within two years.

The owner estimated the cost for that part of renovations at $1.76 million. For another $3.5 million, maximum, he said he could convert what Edwards called “the large Burleigh building” into upscale apartments.

Correction to above article

Benton historian Barbara Warren wrote to point out an error in the Hinds genealogy in the Aug. 4 piece on natural resources, the section on Augustine Crosby (1838-1898), who invented a gold dredge and married Asher Hinds’ daughter, Susan Ann Hinds (1837-1905).

This writer incorrectly identified Susan Hinds’ father as Asher Crosby Hinds, known as “the Parliamentarian.” Her father was actually Asher Hinds (1792- 1860), whom Warren calls “the builder” (he sponsored the building of the Benton Falls Meeting House in 1828 and in 1830 built the Benton Falls house in which Warren now lives). Warren describes him as “a prosperous farmer and merchant,” War of 1812 veteran and delegate to the Massachusetts General Court.

Susan Ann (Hinds) Crosby was Augustine Crosby’s third cousin and Parliamentarian Asher Crosby Hinds’ aunt. Her brother, another Asher Crosby Hinds, was born in 1840 and died in 1863 in the Civil War. The Parliamentarian’s father was Susan’s brother, Albert Dwelley Hinds (1835-1873).

The confusion is understandable, Warren wrote. For four generations, the Hinds family included an Asher; and Hinds and Crosbys often intermarried.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Thurlow, Clinton F., The WW&F Two-Footer Hail and Farewell (1964).

Websites, miscellaneous.

by Mary Grow

by Mary Grow