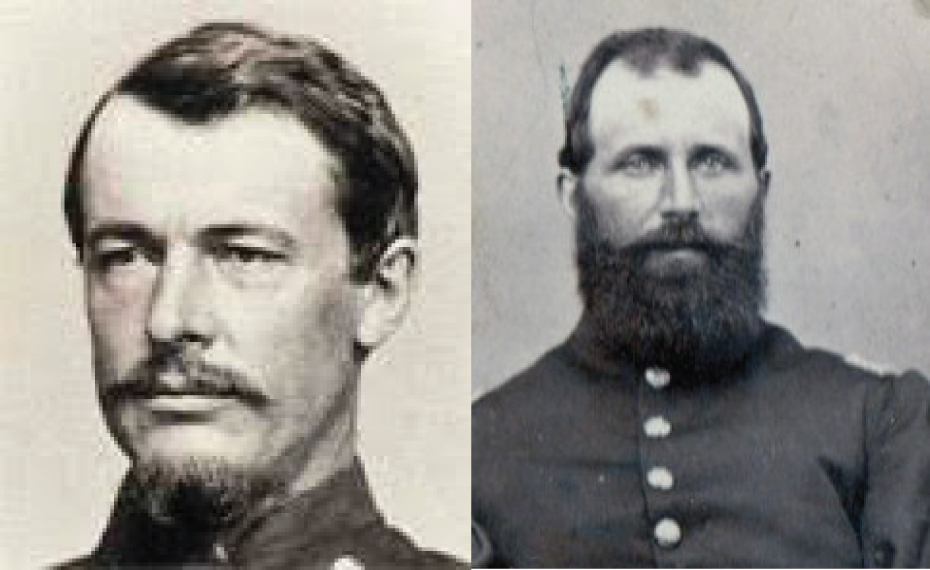

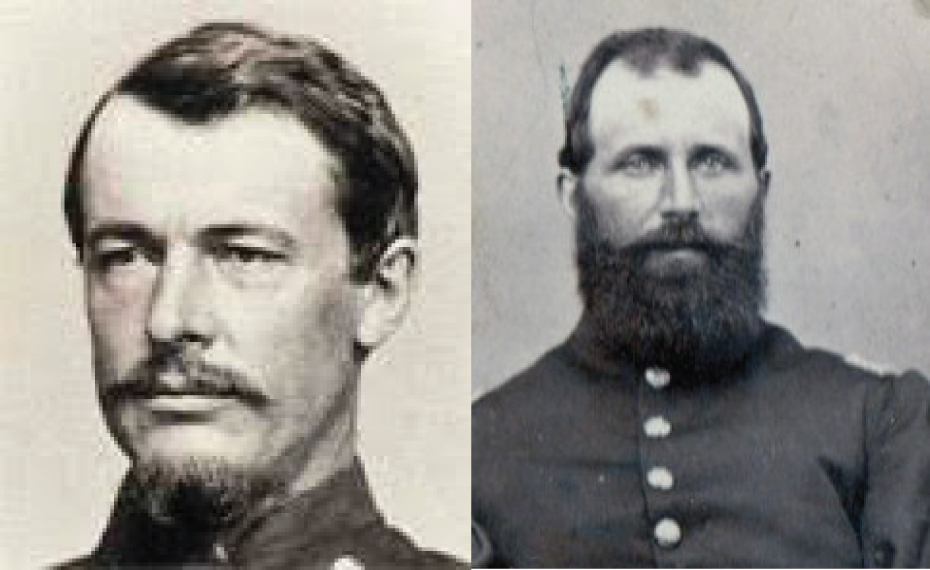

Capt. James Parnell Jones (left), Capt. Charles W. Billings (right)

Civil War

Henry Kingsbury lists four men who served in “the late war” in the personal paragraphs in his chapter on Benton in the 1892 Kennebec County history.

Stephen H. Abbott enlisted from Winslow and served six months with the 19th Maine; he moved to Benton in 1872 and served as postmaster from 1890 and for three years as a selectman.

Gershom Tarbell was in the 19th Maine for three years. Albion native Augustine Crosby was in the 3rd Maine, credited to Benton. Hiram B. Robinson was in Pennsylvania when the war started and enlisted from there not once but twice; he fought in 37 battles and returned to Benton in 1865.

Kingsbury does not mention Benton-born Frank H. Haskell (1843-1903), described in on-line sources as enlisting in Waterville June 4, 1861, when he was 18. Sergeant-Major Haskell was promoted to first lieutenant in the 3rd Maine Infantry after being cited for heroism during the June 1, 1862, Battle of Fair Oaks (also called the Battle of Seven Pines) in Virginia. His action, for which he received a Medal of Honor, is summarized as taking command of part of his regiment after all senior officers were killed or wounded and leading it “gallantly” in a significant stream crossing.

Another Civil War soldier from the central Kennebec Valley who was awarded the Medal of Honor was Private John F. Chase, from Chelsea, who enlisted in Augusta and served in the 5th Battery, Maine Light Artillery. As the May 3, 1863, battle at Chancellorsville, Virginia, wound down, Chase and one other survivor continued firing their gun after other batteries stopped and, since the horses were dead, dragged the gun away by themselves to keep it from the Confederates.

Grave of Horatio Farrington

At least 40 China residents died of wounds or disease, including, the China bicentennial history says, the five oldest of Mary and Ezekiel Farrington’s seven sons. Horatio, age 27, Charles, 25, Reuben, 20, Byron, 19 and Gustavus, 18, died between June 1, 1861, and Oct. 30, 1864.

Records do not show how many Civil War veterans were permanently disabled, the author commented. She retold the story told to her by Eleon M. Shuman of Weeks Mills about Jesse Hatch, from Deer Hill in southeastern China, who (for an unknown reason) fought for the South and came home so disfigured from a powder magazine explosion “that his appearance frightened the neighborhood children, but his friendly words and gifts of apples made him less terrifying.”

One of China’s best-known Civil War soldiers was Eli and Sybil Jones’ oldest son, Captain James Parnell Jones. As the author of the China history pointed out, pacificism is a central Quaker tenet, but in 1861 some Quakers decided ending slavery and maintaining the Union outweighed religious upbringing.

She quoted from the Jones genealogy an account of James Jones (who was 23, married with one son) and his 18-year-old unmarried brother Richard at a troop-raising event.

“Richard immediately raised his hand when the call came but James walked over to his brother, pulled down the raised arm and slowly raised his own. ‘Thee’s too young, Richard.’ ”

Jones was in the 7th Maine, first a company captain and from December 1863 a regimental major, as the troops fought in Virginia and at Gettysburg. In 1864, in the Battle of the Wilderness, he allegedly replied to a demand to surrender his embattled regiment with, “All others may go back, but the Seventh Maine, never!”

Jones was killed in the fighting around Fort Stevens July 11 and 12, 1864, as the 7th Maine helped defend Washington.

From Clinton, Kingsbury listed Daniel B. Abbott, born in Winslow, who served in the 19th Maine until June 1865 and after the war bought a farm in Clinton and became commander and grand master of Billings Post, G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic, the Civil War veterans’ organization that was disbanded in 1956 after the last member died).

The post was named to honor Captain Charles Wheeler Billings (Dec. 13, 1824 – July 15, 1863), Company C, 20th Maine, who was wounded in the left knee July 2, 1863, at the Battle of Little Round Top and died in a field hospital.

Clinton’s Brown Memorial Library website and a “Central Maine Morning Sentinel” article found on line describe the June 6, 2015, rededication of Clinton’s Civil War monument and the monument at Billings’ gravesite in Riverview Cemetery. The newspaper quotes speaker Bruce Keezer, then President of the Friends of Brown Memorial Library, as saying Clinton had a total population of 1,600 in the early 1860s; 252 men enlisted and 32 died.

The website says Billings was the highest-ranking 20th Maine officer to die at Little Round Top.

Billings left a widow, Ellen (Hunter) Billings, whose 30th birthday was July 1, 1863, and two daughters: Isadore Margaret, born in 1850, and Elizabeth W., or Lizzie, born in 1860. Another daughter, Alice, born in 1856, had died in 1860; and Elizabeth died Dec. 7, 1863. Isadore died in 1897, the day after her 47th birthday. Ellen lived until 1924.

Also from Clinton, according to Kingsbury, were Isaac Bingham, Rev. Francis P. Furber, Joseph Frank Rolfe and Laforest Prescott True.

Bingham had gone to California in 1852; he came home in 1861 and served two years with the 1st Maine Cavalry. After the war he moved back and forth between his Clinton farm and California.

Furber, a Winslow native who moved to Clinton in 1845, served in the 19th Maine for three years. A wound received May 6, 1864, “destroyed the use of one arm,” Kingsbury wrote. He was ordained a Freewill Baptist minister Sept. 27, 1885, after serving as a minister in Clinton and nearby towns since 1875.

Rolfe, born in Fairfield of parents who moved to Clinton when he was about three, served in the 2nd Maine Cavalry from 1863 to the end of the war. True was in the 20th Maine from 1862 to 1865 and was wounded twice.

Fairfield’s Civil War monument is one of the oldest in Maine, according to the town’s bicentennial history. The writers noted that its dedication day, July 4, 1868, was a scorching Saturday: the temperature reached 105 degrees in the shade.

Soldiers came from all over Maine. Ceremonies included a parade; cannon salutes; speeches, including one by Governor (former General) Joshua Chamberlain; dinner prepared by townswomen and served “in the old freight depot”; and a baseball game with a final score of 60 to 40 (the history does not record the names of the teams).

“The day was not without its tragedy,” the history says. A veteran named William Ricker, who had survived the war unscathed, lost a hand when one of the cannons went off too soon. Chamberlain promptly canceled the remaining salutes.

Kingsbury found that one of Sidney’s soldiers, Mulford Baker Reynolds (Aug. 5, 1843 – Aug. 3, 1937) served in Company C of the 1st Maine Cavalry from August 1862 to July 1865, “and spent about six months in Andersonville prison” in Georgia.

Reynolds married Ella F. Leighton on Nov. 23, 1881, according to an on-line source. Kingsbury wrote that in 1892 Reynolds was farming his family place in Sidney and he and Ella had four children.

Among the many Vassalboro men whose personal paragraphs in Kingsbury’s history list Civil War service is Edwin C. Barrows (April 2, 1842 – April 20, 1918). Educated at Waterville and Bowdoin colleges, he enlisted Nov. 19, 1863, in the 2nd Maine Cavalry.

Transferred in June 1865, he became second lieutenant (but acted as adjutant, the officer who assists the commander with administration, Kingsbury wrote) of the 86th U.S.C.T. (United States Colored Troops), serving until he was discharged April 10, 1866.

After the war, Barrows got a law degree from Albany Law School in January 1867 and practiced four years in Nebraska City, Nebraska. He married Laura Alden (Sept. 5, 1842 – Dec. 19, 1909) and returned to Vassalboro in 1872. By 1892, he had been a supervisor of schools in 1882 and 1883 and since then a selectman, “being chairman since 1887.”

Edwin and Laura Barrows are buried under a single headstone in Vassalboro’s Nichols Cemetery.

Vassalboro’s G.A.R. Post was named in honor of Richard W. Mullen of the 14th Maine, one of 410 Vassalboro Civil War soldiers, Alma Pierce Robbins wrote in her town history. After the war, town meeting voters appropriated money to the G.A.R.’s Women’s Relief Corps for Memorial Day services and veterans’ grave markers. The Post disbanded in 1942 and the appropriation was transferred to Vassalboro’s American Legion Post and Auxiliary.

The Waterville G.A.R. Post, chartered Dec. 29, 1874, was named in honor of William S. Heath, who was killed in action at Gaines Mill, Virginia, on June 27, 1862. The first post commander was General Francis E. Heath, the second General I. S. Bangs. Francis Heath was almost certainly William Heath’s brother (variously identified as Frank Edw. and Francis E.; died in Waterville in December 1897), I. S. Bangs the author of the military history chapter in Edwin Whittemore’s Waterville history.

Ernest Marriner added information on William Heath’s life in “Kennebec Yesterdays”. In 1849, he wrote, Heath was 15 and “somewhat tubercular”; his father, Solyman, thought a trip to the goldfields in California would be good for him.

Young Heath “did survive the rigors of the terrible trip across plains and mountains, worked a while in a San Francisco store, then shipped off to China, from which distant land the anxious father soon had him returned through the intercession of the United States government.”

Back in Waterville, Heath graduated from Waterville College in 1853. When the 3rd Maine’s Company H was formed in Waterville in April 1861, Heath was captain and his brother Francis/Frank was first lieutenant. By the time of his death, William Heath was a lieutenant colonel in the 5th Maine Infantry, Marriner wrote. Francis ended the war as a colonel in the 19th Maine, according to Bangs.

Linwood Lowden, in his Windsor history, wrote that Charles J. Carrol, one of seven Windsor men who fought in the Battle of Gettysburg July 2-4, 1863, was mortally wounded. Three more Windsor men, George H. B. Barton, George W. Chapman and George W. Merrill, were killed May 6, 1864, in the Battle of the Wilderness.

Windsor’s Vining G.A.R. Post, organized June 2, 1884, was named to honor Marcellus Vining. Post members met every Saturday night in the G.A. R. Hall, which was the upper story of the town house, Lowden said.

At an 1886, meeting, “a Mr. Bangs presented a picture of Marcellus Vining” to the organization. Kingsbury added that the Vining family donated Marcellus Vining’s army sword, “his life-size portrait and an elegant flag.”

Lowden believed Vining Post continued “well into the twentieth century.” Windsor voters helped fund the G.A.R., usually at $15 a year, he wrote. In 1929, however, “$30.00 was appropriated for G.A.R. Memorial and paid to the Sons of Veterans.”

Kingsbury wrote that Vining was born on the family homestead on May 2, 1842, third child and oldest son of Daniel Vining by his first wife, Sarah Esterbrooks of Oldtown (Daniel and Sarah had three daughters and three sons; after Sarah’s death, Daniel married Eliza Choat, and they had six more daughters).

On Jan. 25, 1862, Marcellus Vining became a private in the 7th Maine. He served for two years, during which his “ability and courage” (Kingsbury) earned him two promotions. On Jan. 4, 1864, he re-enlisted in a reorganized 7th Maine. On March 9 he was made second lieutenant of Company A, and on April 21 made first lieutenant. On May 12 he was wounded at Spottsylvania, Virginia; he died a week later.

“A captain’s commission was on its way from Washington to him, but too late to give to the brave soldier his richly earned promotion,” Kingsbury wrote.

He continued with a paraphrase from a letter Vining, knowing he was dying, wrote to his father, saying it was better “to die in the defense of his country’s flag than live to see it disgraced.”

Kingsbury concluded: “Thus the oft-repeated tale—a bright, promising man with the blush of youth still on his cheek, willingly laid down his life to preserve that of his country.”

Main sources

Fairfield Historical Society, Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988)

Grow, Mary M., China Maine Bicentennial History including 1984 revisions (1984)

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

Lowden, Linwood H., good Land & fine Contrey but Poor roads a history of Windsor, Maine (1993)

Marriner, Ernest, Kennebec Yesterdays (1954)

Robbins, Alma, Pierce History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971)

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902)

Websites, miscellaneous

by Mary Grow

by Mary Grow