Nelson, the horse owned by Charles Horace “Hod” Nelson, of Waterville. (photo courtesy of Lost Trotting Parks Heritage Center)

Waterville horses continued “Nelson”

Another locally-bred trotting horse, even more famous than General Knox (described last week), was Nelson.

Nelson was a bay horse. The color is described on line as “a reddish-brown or brown body color with a black point coloration on the mane, tail, ear edges, and lower legs.” Several on-line pictures dramatically contrast his dark mane with his lighter body. He stood a little over 15 hands (readers will remember a hand equals four inches).

He was born in 1882, probably in January. Various on-line sources say his sire (father) was Young Rolfe, born in Massachusetts and brought to Waterville by Charles Horace “Hod” Nelson, owner of Sunnyside Farm, before he was a year old.

Nelson’s dam (mother) was Gretchen, a daughter of Gideon, who was a son of Hambletonian. Thomas Stackpole Lang, of Vassalboro, brought Gideon to Maine around 1860, one of many well-bred horses he introduced to the Kennebec Valley.

Hambletonian (1792 – March 28, 1818) was a famous British Thoroughbred who won 18 of his 19 races before being retired to stud in 1801. The Hambletonian Stakes for three-year-old trotters, run annually since 1926, honors the British horse. This year’s race was held Aug. 5 at Meadowlands, in New Jersey.

The horse “Nelson”

Nelson the man (whom your writer will disrespectfully call “Hod” throughout this article to minimize confusion) bred, trained, raced and deeply loved Nelson the horse. Stephen D. Thompson’s long and well-researched article on the website losttrottingparks.com, titled “When Waterville was Home to Nelson, the Northern King,” gives a great deal of information about horse and man.

Nelson first attracted attention in 1884, winning a race for two-year-olds at the state fair in Lewiston. At the 1885 state fair in the same city, he won two cups, as the fastest three-year-old and the fastest stallion, and set a record.

He continued his winning ways in 1889 in Boston, Massachusetts, and in Buffalo, New York, where he won a $5,000 stake before, Hod wrote, 40,000 people.

On Sept. 6, 1890, in Bangor, he set a world record for a half-mile track. From there he was shipped to Illinois, where, on Sept. 29, 1890, in Kankakee, he set what Samuel Boardman, in his chapter in Kingsbury’s Kennebec Cunty history, called “the champion trotting stallion record of the world” over what Thompson said was a mile-long track.

This record stood for a year, Boardman wrote, until September 1891, when it was broken in Grand Rapids, Michigan – by Nelson.

After September and October 1890 races in Illinois and Indiana, Nelson and Hod returned to Sunnyside for the winter. In November, Hod, but presumably not Nelson, attended a “Banquet in celebration of the Champion Trotting Stallion Nelson at the Elmwood Hotel.”

Due to rumors that the 1889 Boston race had been fixed, Nelson and Hod were suspended by the National Trotting Association from December 1890 to Dec. 6, 1892. (Thompson wrote that Hod had refused to fix the race, but apparently someone else did and Hod was somehow caught up in the scheme.)

The suspension did not preclude racing, apparently, because E. P. Mayo, in his chapter in Edwin Whittemore’s Waterville history, described Nelson’s many journeys and busy fall schedules in 1891 and 1892.

Hod took Nelson to Michigan in October 1891 (or earlier? – see Boardman, above) for more racing; this time, according to Thompson’s account, he lost one race. Mayo said this western tour, “which was nothing short of a triumphal procession,” began in Saginaw, Michigan, and included nine cities in Michigan, Iowa and Indiana.

The duo apparently returned immediately to Maine, because on October 30, Thompson wrote, Nelson left Waterville “[i]n his own train car” with three grooms and Hod for Chicago’s American Horse Show. He was received enthusiastically at stops along the way and “Became the idol of the show!”

(Mayo said Nelson’s triumph at the Chicago horse show was in 1890, rather than 1891; he, too, said Nelson returned from Indiana and rested a week in Maine before heading to Chicago, and he, too, used the word “idol.”)

In 1892 and 1893, Mayo wrote, Nelson continuing racing and exhibiting at many tracks, from New Jersey through New England to New Brunswick.

On June 24, 1902, Hod drove Nelson in Waterville’s Centennial parade. According to William Abbott Smith’s account in Whittemore’s history, they were right behind the carriages containing “invited guests,” city officials and the centennial organizing committee.

After Hod and Nelson, Smith wrote, came “Horses from Sunnyside Farm, driven by young ladies, two mounted, handsomely arrayed.”

At his last public appearance, on “Nelson Day” (honoring both horse and man), held Sept. 10 at the 1907 Central Maine Fair, in Waterville, Nelson “received the cheers of thousands as he went around the track with his old time style, and was visited by thousands in his stall” (according to a Dec. 9, 1909, Waterville Sentinel obituary for the horse that Thompson quoted).

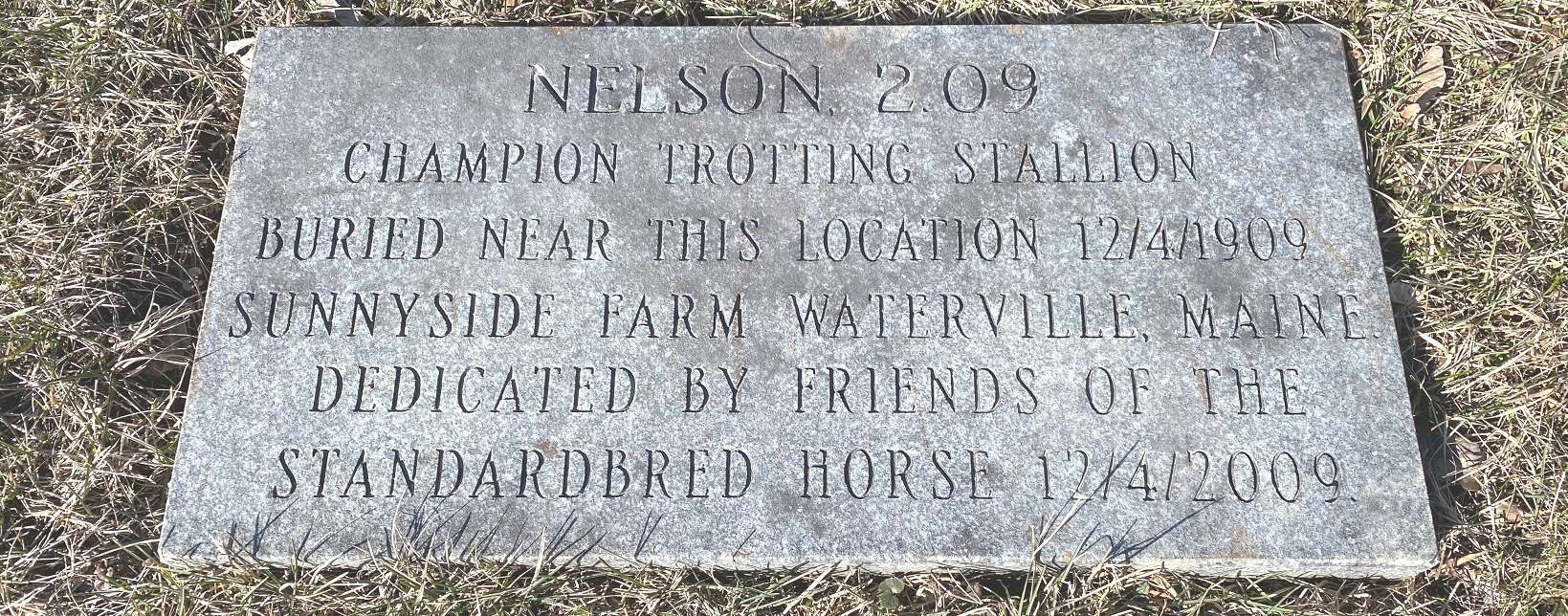

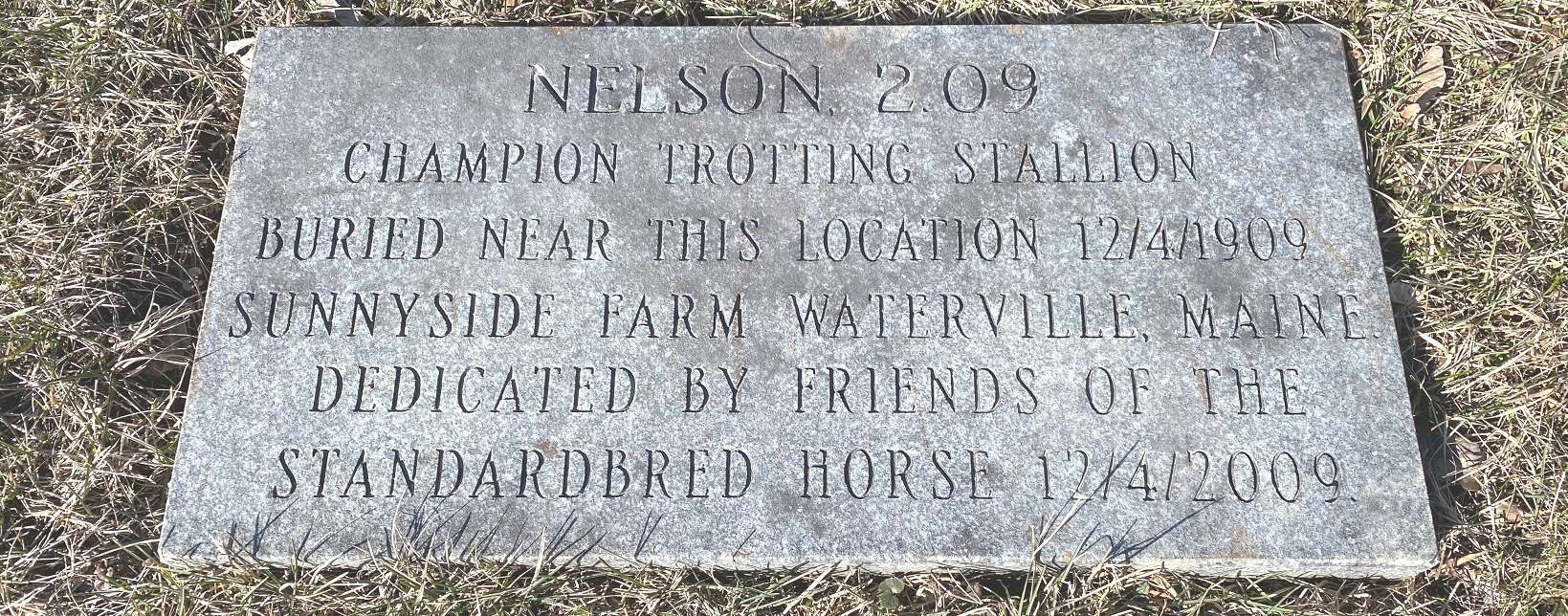

Hod put Nelson down on Dec. 1, 1909, at Sunnyside Farm. Thompson described plans for his burial and grave marker, but apparently failed to find the marker or its presumed location.

An inscribed granite marker at the Sterling Street Playground, in Waterville, honoring the life of Nelson. The playground is part of what was once Sunnyside Farm, the home of Nelson. (photo by Roland Hallee)

In the Sentinel article, Hod described his horse as “a clever old fellow and…kind to everybody. In all his life he has only bitten at two or three persons and would not have done so then had they let him along [sic] or had they not been intoxicated. He could tell when a man had been drinking and seemed to take a dislike to them on that account.”

Hod added that someone offered him $125,000 for Nelson when the horse was eight years old, and he refused.

In 1994, Nelson was elected to the Harness Racing Hall of Fame’s Hall of Immortals, horse division. One source says he was the only Maine-bred trotting horse so honored.

Another indication of his fame, according to on-line sources, is that Currier and Ives made six prints of Nelson. The famous New York City printmakers also did portraits of Lady Maud and Camors, two of many horses sired by Thomas Stackpole Lang’s General Knox.

Charles Horace “Hod” Nelson

“Hod” Nelson

Hod Nelson was born April 16, 1843, in Palermo (or China; sources differ), the younger son of a storekeeper named Benjamin Nelson and his wife Asenath (Brown) Nelson. Hod spent his life farming and breeding horses, with an interruption during the Civil War.

According to the Find a Grave website, quoting submitted information, Hod enlisted in the 19th Maine Infantry as a private on Aug. 1, 1862; was “discharged for disability” March 13, 1863; re-enlisted as a private in the 12th Maine Infantry on Oct. 2, 1865; and was promoted to first sergeant before his honorable discharge March 3, 1866. Later, he was commander of Waterville’s W. S. Heath G.A.R. Post.

On Nov. 7, 1867, Hod married Emma Aubine Jones, who was born in China, Jan. 31, 1848, the only child of Francis and Eliza (Pinkham) Jones. An on-line genealogy lists no children of the marriage.

Hod owned a farm in China until 1882, when he bought what became Sunnyside Farm, off the Oakland Road – now Kennedy Memorial Drive (KMD) – in Waterville.

Thompson, through diligent research, established that Sunnyside Farm was on the south side of KMD between Nelson and Carver streets. He quoted an 1888 description that said there were actually two farms on the 540 acres of pasture and hayfields.

The farm for the brood mares and foals included three barns and “a fine residence” (presumably Hod and Emma’s home). The farm for the stallions had “two large barns” – and in 1888 a third was being planned – and a “substantial, old-fashioned house” where the employees lived.

By April 1894, Hod had another farm in Fairfield, mentioned in an April 23, 1894, article in The Kennebec Journal that Thompson found. Nelson’s dam, Gretchen, age 27, was still living at Sunnyside, and still had “the same fine limbs, the same straight back, and general proportions of beauty as a filly of four or five.”

Hod had 76 horses at Sunnyside and 41 “brood mares and colts” at his Fairfield farm, according to the article.

Later in life Hod suffered health issues – Thompson mentioned his war-related disability – and financial problems. By mid-March 1915 he was seriously ill, and Emma, who was caring for him, had a stroke. Her nephew took Hod to the veterans’ home at Togus, where he died on March 29, 1915.

Emma recovered and lived in a Waterville apartment until her death on Aug. 12, 1916, Thompson wrote. (An on-line genealogy dates her death Aug. 11, 1916.)

Hod and Emma Nelson are buried in Waterville’s Pine Grove Cemetery. One on-line genealogical source says the same cemetery holds the graves of Hod’s brother, Edward White Nelson (1841 – Nov. 9, 1906), Edward’s wife Cassandra Marden Worthing (born in Palermo, July 16, 1843, and died in Waterville Dec.7, 1903) and at least three of their four children, Hod’s nieces and nephew.

The Find a Grave website does not list Edward or Cassandra Nelson in Pine Grove cemetery. It does show the tombstone of their son (and Hod’s nephew), lawyer and Congressman John Edward Nelson (July 12, 1874 – April 11, 1955).

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Website, miscellaneous.

Saturday, September 30, 2023, family members of World War II soldier from Palermo, Malcolm Leroy Glidden, honored his memory with a gathering at the Malcolm Glidden American Legion Post #163, in Palermo. The presentation was put together by Post Commander Paul Hunter with documentation that he researched and obtained from the National Archives in St. Louis, Missouri, and information from other sources like Newspapers.com, Ancestry.com, Sons of Liberty Museum and American Legion records. It was supplemented by historic records, clippings and photos that Mr. Glidden’s parents, George and Esther Glidden, had saved from the 1940s. Two of their granddaughters, Patricia (Pat) Glidden Clark and sister Laraine Glidden (daughters of Malcolm’s brother Lawrence) provided a great deal of information to the Legion.

Saturday, September 30, 2023, family members of World War II soldier from Palermo, Malcolm Leroy Glidden, honored his memory with a gathering at the Malcolm Glidden American Legion Post #163, in Palermo. The presentation was put together by Post Commander Paul Hunter with documentation that he researched and obtained from the National Archives in St. Louis, Missouri, and information from other sources like Newspapers.com, Ancestry.com, Sons of Liberty Museum and American Legion records. It was supplemented by historic records, clippings and photos that Mr. Glidden’s parents, George and Esther Glidden, had saved from the 1940s. Two of their granddaughters, Patricia (Pat) Glidden Clark and sister Laraine Glidden (daughters of Malcolm’s brother Lawrence) provided a great deal of information to the Legion.

submitted by Maria O’Rourke,

submitted by Maria O’Rourke,