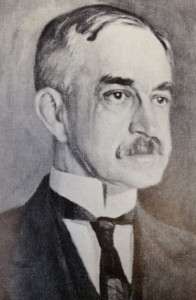

Martin Keyes

Here is Earl H. Smith’s introduction to Martin Keyes in Smith’s Downeast Genius, beginning with a comparison to the inventor profiled in this series two weeks ago.

“Like Alvin Lombard, Martin Keyes (1850–1914) was blessed with an inquisitive and clever mind, but unlike his burly tractor-making neighbor, Keyes was a diminutive and fastidious man. He kept a diary every day, and it was his thorough way that led him to claim an invention that established one of Maine’s most successful international industries.”

Keyes’ profile in the Paper Industry International Hall of Fame, in Appleton, Wisconsin, says he was born Feb. 19, 1850, in Lempster, New Hampshire. Smith wrote that he first worked in his father’s sawmill, then established his own business making “sleighs and carriages.”

The Hall of Fame and other sites credit young Keyes with designing a furniture line (called “exquisite”) and “a new type of fishing reel” that he used the rest of his life. An on-line site says he kept a pad and pencil by his bed in case he thought of an invention during the night.

Smith and the Hall of Fame disagree on where Keyes got the inspiration for his major invention, and neither provides a date. Smith wrote that while working at “a veneer mill in upstate New York,” he saw workmen eating lunches off thin scraps of veneer and came up with the idea of making disposable plates out of molded pulp.

His first efforts using veneer failed, Smith wrote. Later, Keyes became superintendent at Indurated Fiber Company, in North Gorham, Maine; it was there, the Hall of Fame writer said, that he got the idea of making the plates from molded pulp.

Both sources agree he began figuring out how to manufacture his disposable plates at Indurated, “with the support of his employer,” Smith added. After “several years of experimenting,” he designed a machine that would make the plates.

The section on the Keyes Fibre Company in the Fairfield history offers a third version of the story. According to that writer, Keyes became Indurated’s superintendent in 1884, and the North Gorham company already made “tubs, pails, and small pressed pulp ware.” When the North Gorham mill burned, Keyes transferred to another Indurated facility in northern New York, which was where he saw workmen eating off veneer chips from nearby plants.

The former Keyes Fibre Co., in Waterville/Fairfield, now Huhtamaki.

Two historians again offer conflicting views of what happened when Keyes tried to patent his machine. In the version in the Fairfield history, a “large paper manufacturer in eastern New York” offered him $100,000 to build a machine to make plates from pulp.

In 1902, Smith said, Keyes had the first machine manufactured, at Portland Iron Works (in Gorham, he had worked with a man associated with the company). Smith described it: “With flailing arms that hissed and groaned as they rotated through a process of dipping, drying, ejecting, and packaging, the finished apparatus resembled the complicated contrivances of the cartoonist Rube Goldberg.” (See box.)

The Fairfield history say the upstate New York paper company “tried to claim the patent.” Smith’s version is that when Keyes applied for a patent, he learned that another worker had “stolen his idea” and already patented it.

The two versions reach the same conclusion: Keyes went to court and, after extended litigation, won. In Smith’s book and in an undated on-line history of the Keyes Fibre Company, written by the eminent local historian Dean C. Marriner, Keyes’ daily diary provided the evidence to convince a jury that he had done the work to design the machine and therefore earned the patent.

His next problem, the Fairfield historians wrote, was to find capital to start a factory. Eventually he connected with a Fairfield company, Lawrence, Newhall and Page, which ran lumber mills. This company had at Shawmut “one grinder installed already for the production of mechanical pulp.”

Keyes built “a small shack” on the side of the grinder building and built one experimental machine (Smith wrote that he rented space in the Shawmut plant). On Nov. 2, 1903, the Fairfield history says, the company he named Keyes Fibre started production, with that single machine.

The Hall of Fame writer said the first shipment of “pulp molded pie plates” went out in 1904 (other writers add that this sale led local residents to call the manufactory “the pie plate”).

Multiple sources credit a local man named Bert Williamson with helping Keyes get his plant up and running. Marriner wrote, “Williamson was at the inventor’s side when the first shipment of a carload of molded pulp pie plates, for the use of bakers, left the Shawmut plant on June 24, 1904.” Williamson remained with the company for two decades after Keyes’ death.

In 1905, the Fairfield history says, Keyes built “a small plant” with four machines. Smith wrote that early production was 50,000 plates daily, without explaining whether he was talking about one machine or four.

However, the Hall of Fame site says, Keyes’ plates were priced higher than competing products, described on-line as “stamped paper plates.” In early 1905, Keyes closed his plant for several months.

He acquired new investors, including his landlords, Lawrence, Newhall and Page, added more of his own money and reduced prices to restart production. After the April 18, 1906, San Franciso earthquake and fire, demand increased – one buyer ordered an entire carload of plates.

But then, Marriner wrote, Lawrence, Newhall and Page sold the pulp mill. The new owners let Smith continue to use their facility, but they sold within a year to another company not interested in wood products, forcing Keyes to relocate.

Keyes considered sites in Maine and elsewhere. Marriner said he and Williamson checked out possibilities in upstate New York over the 1907 Labor Day weekend, attending a parade in which many of the marchers were drunk.

Keyes, a Prohibitionist, reportedly said to Williamson, “Bert, you and I could never use that kind of labor.” (Smith located this incident in Portland, writing that when Keyes visited the city, “he was dismayed to find many drunken workers.”)

Keyes moved to Waterville, buying “a site immediately north of Lombard’s tractor factory” (per Smith) on the east side of what is now College Avenue.

Here he built what Marriner called “a modest brick building, which turned out its first plates on Sept. 20, 1908, and is still the nucleus of the giant plant that now stretches half a mile along the roadway,” partly in Waterville and partly in Fairfield. The plant, since 1999 owned by and called Huhtamaki, produces “a variety of pulp-molded products.”

Keyes died Nov. 18, 1914, in Fairfield. By that time, according to a Dec. 2, 1914, obituary in a New York weekly journal of the pulp and paper industry called simply Paper (found on line), Keyes Fibre could produce almost two million pie plates every 24 hours, providing an estimated “four-fifths of all the pie plates used in the United States and Canada.”

Your writer was unable to find personal information about Keyes except in the obituary. It recapped his career and said that survivors included his mother, Mrs. L. A. Gilmore, of Holyoke, Massachusetts; his widow, Jennie C. Keyes; two brothers, in Minnesota and New York; a sister in Holyoke; and a daughter, Mrs. George G. Averill.

Another source says Mrs. Averill’s first name was Mabel. Keyes’ son-in-law, Dr. George Goodwin Averill (1869 – 1954), took over the management of the company.

Keyes is recognized by Keyes Memorial Field (now Keyes Memorial Athletic Fields), on West Street, in Fairfield. The Fairfield history says his widow gave it to the town on Oct. 1, 1938.

* * * * * *

If Frank Bunker Gilbreth’s name sounds familiar, it might be because two of his 12 children, Frank Bunker Gilbreth, Jr., and Ernestine Moller (Gilbreth) Carey, wrote a “semi-autobiographical novel” titled Cheaper by the Dozen, published in 1948. Cheaper by the Dozen was made into a movie in 1950 and has been variously adapted since.

The real Frank Bunker Gilbreth was born July 7, 1868, in Fairfield. He was the son of John Hiram Gilbreth (born in Augusta in 1833, died in Fairfield in 1871) and Martha (Bunker) Gilbreth (born in Maine about 1834, died in Montclair, New Jersey, about 1920), and the brother of Mary Elizabeth Gilbreth, born in Fairfield in 1864 and died in Brookline, Massachusetts, Aug. 8, 1894.

His main claim as an inventor, in Smith’s view, was as an efficiency expert. An on-line site called him “The Father of Management Engineering.”

Gilbreth started, Smith wrote, by graduating from Boston English High School and declining to attend Massachusetts Institute of Technology in favor of becoming a bricklayer’s apprentice.

After 1895, Smith wrote, Gilbreth was “a self-employed general contractor” who built “mills, dams and power plants” in the United States and Europe. “Along the way, he invented a number of building tools and machines including a safety scaffold for bricklayers, conveyors, and an improved concrete mixer.”

Managing so many projects “led him to formulate the first cost-plus-fixed sum contract and to develop a number of systems to reduce waste, monitor work progress, and improve the productivity of his workers.”

In 1904, Gilbreth married a psychologist, Lillian Evelyn (Moller) Gilbreth (1878 – 1972). She worked with her husband on time and motion studies; the two “built a reputation as efficiency experts.”

Gilbreth died June 14, 1924, in Montclair, New Jersey. His body was cremated and the ashes scattered over the Atlantic.

A gravestone in Fairfield’s Maplewood cemetery has his and Lillian’s names and dates. His parents and sister are also buried there.

Rube Goldberg machine

The expression “Rube Goldberg machine” means a very complicated way of doing a simple task. It recognizes the inventiveness of cartoonist, engineer and movie-maker Reuben Garrett Lucius Goldberg.

The expression “Rube Goldberg machine” means a very complicated way of doing a simple task. It recognizes the inventiveness of cartoonist, engineer and movie-maker Reuben Garrett Lucius Goldberg.

Born in San Francisco July 4, 1883, Goldberg earned an engineering degree at University of California, Berkeley, Class of 1904. He began his career as a sports cartoonist in California and moved to New York City in 1907, where he earned fame as a cartoonist for various newspapers and other publications.

Goldberg and his wife, Irma Seeman (married in 1916) had two sons, Thomas and George (who both changed their last names to George). Goldberg died Dec. 7, 1970.

Goldberg’s cartoons won several awards, including a Pulitzer Prize in 1948. Wikipedia says he was one of the founders and the first president of the National Cartoonists Society (1946), whose annual award is named the Reuben Award.

On-line sites say the 2023 Reuben Award winner is Bill Griffith (full name William Henry Jackson Griffith), of New York City, best known as the creator of the “Zippy” comic strip.

Main sources

Fairfield Historical Society Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988).

Smith, Earl H., Downeast Genius: From Earmuffs to Motor Cars Maine Inventors Who Changed the World (2021).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Recycled Shakespeare Company (RSC) will hold auditions for their upcoming play Richard III on Sunday, November 26, 5 to 7 p.m., at South Parish Congregational Church, in Augusta, and Monday, November 27, 5 to 7 p.m., at Fairfield House of Pizza, in Fairfield.

Recycled Shakespeare Company (RSC) will hold auditions for their upcoming play Richard III on Sunday, November 26, 5 to 7 p.m., at South Parish Congregational Church, in Augusta, and Monday, November 27, 5 to 7 p.m., at Fairfield House of Pizza, in Fairfield.

Lane Closures:

Lane Closures:

Alfond Youth & Community Center and Mid-Maine Chamber of Commerce combine efforts to present Festival of Trees this holiday season, continuing a proud tradition reinvigorated last season, with a change of venue to the Waterville Elks Lodge.

Alfond Youth & Community Center and Mid-Maine Chamber of Commerce combine efforts to present Festival of Trees this holiday season, continuing a proud tradition reinvigorated last season, with a change of venue to the Waterville Elks Lodge.