Previous articles have mentioned ponds and lakes in central Kennebec Valley towns with people’s names, like Pattee or Pattee’s Pond, in Winslow. Some of these water bodies are named for early settlers. Your writer intends for the next few weeks to match ponds and people, to the extent permitted by available resources

According to one on-line source, Pattee Pond honors early Winslow resident Ezekiel Pattee (or Paty), born Sept. 3, 1732, in Gloucester, Massachusetts. Your writer found no evidence that Pattee owned land on or near the pond; nor did she find any other explanation for the pond’s name.

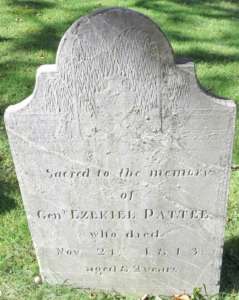

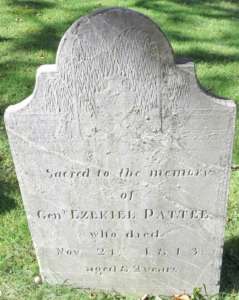

Ezekiel Pattee’s grave marker at Howard Cemetery, on Rte. 201, in Winslow.

Ezekiel’s parents were Benjamin Pattee, Sr. (1696-1787), from Haverhill, Massachusetts, and Patience (Collins) Pattee (1700-1784), from Gloucester. Find a Grave says they married in 1718 or 1720 and had either three sons and three daughters or seven sons and four daughters (two Find a Grave pages differ).

An on-line genealogy says Benjamin was born in Weymouth, Massachusetts, in 1687 (not1696), making him 100 when he died. This source says he and Patience died in Georgetown, Maine. If they moved there before 1760, their relocation might explain why Ezekiel married there, on May 24, 1760.

Ezekiel’s wife was Margaret Howard (1740-May 21, 1821), daughter of Lieutenant Samuel Howard and Margaret Lithgow (though the on-line genealogy erroneously gives her name as Margaret Harward, it adds “OF Fort Halifax, Kennebec, Maine”).

Margaret Lithgow was a sister of Colonel William Lithgow, first commander of Fort Halifax in 1754. Samuel Howard was a brother of Captain James Howard, first commander of Fort Western, in Augusta, in 1754; Samuel served at Fort Halifax as one of Lithgow’s subordinates.

The on-line genealogy lists only two children, Ezekiel and Elizabeth, born to Ezekiel and Margaret. Find a Grave says these were the seventh and eighth of their 11 children, born between 1761 and 1783.

Ezekiel and Margaret named their first son, born in 1761, Samuel (in honor of Samuel Howard?). He died in 1783; and they named their eighth son, born that year, Samuel again.

The second Samuel’s next older brother, born in 1781, they named Lithgow Pattee. Your writer assumes the name honored Colonel William Lithgow.

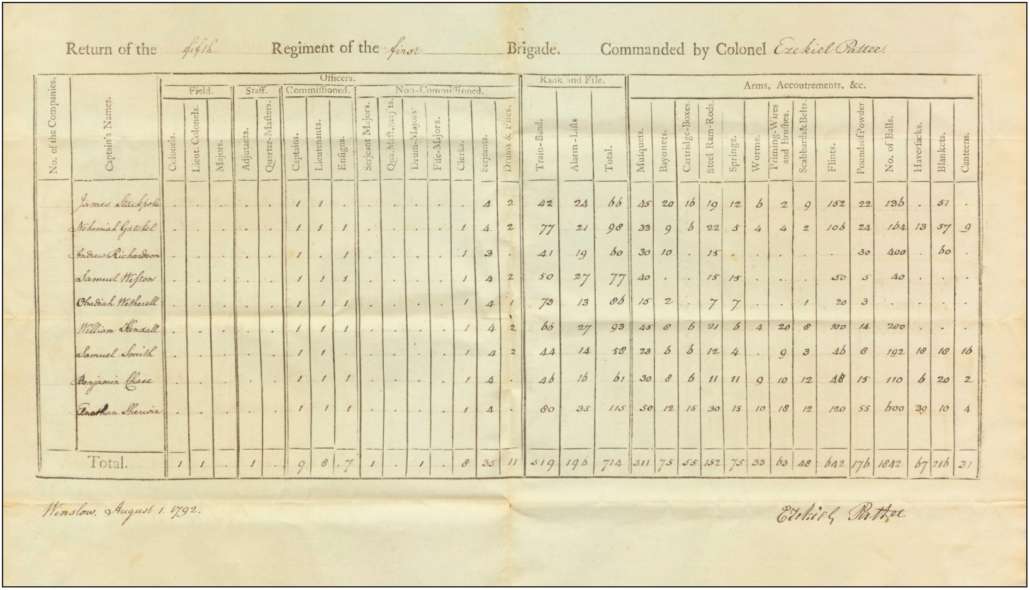

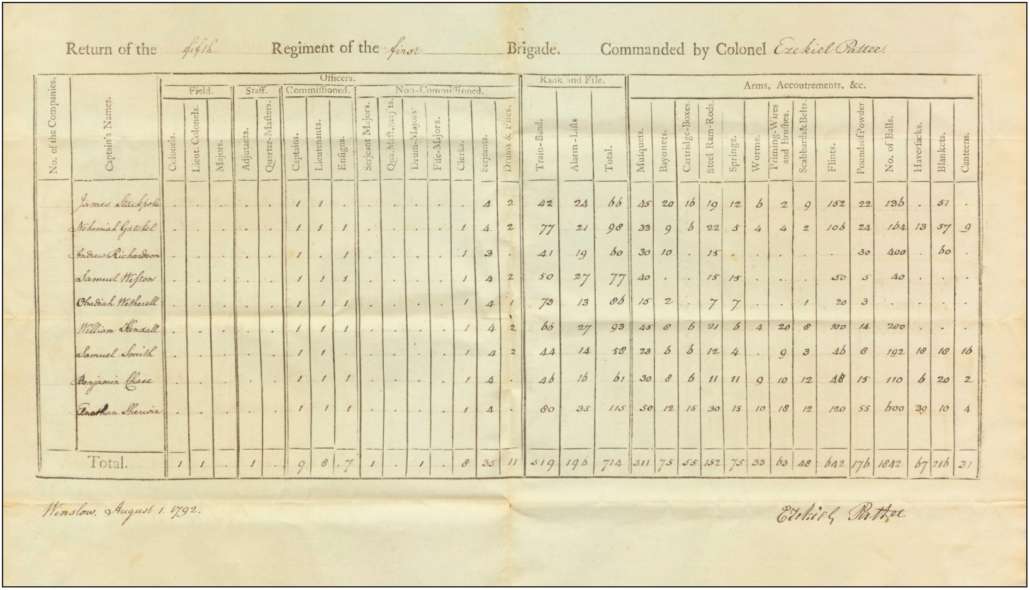

Ezekiel Pattee’s gravestone identifies him as a Revolutionary War veteran and calls him General. A post-war (1792) report in the Maine States archives says he was a regimental colonel in the 8th Division Militia.

Pattee Pond

Henry Kingsbury, in his Kennebec County history, and Edwin Carey Whittemore, in his Waterville centennial history, listed some of Pattee’s contributions to Winslow from the town’s incorporation in 1771.

The warrant for Winslow’s first town meeting, held at Fort Halifax at 8 a.m. on May 23 (a Thursday), 1771, was addressed to “Mr. Ezekiel Pattee, the Freeholders and other inhabitants of Winslow qualified to vote in town affairs,” Whittemore wrote. At the meeting, voters elected Pattee town clerk, town treasurer and one of the three selectmen.

Kingsbury said Pattee served as a selectman for 19 years and as treasurer from 1771 to 1794, except when Zimri Haywood held the post for a year in 1781. He might have been town clerk until 1780, because the next man listed is Haywood, in 1781. Pattee was elected town clerk again in 1782, maybe for three years, and in 1788, maybe for four years.

Under Lithgow’s command, the main part of Fort Halifax was guarded by two blockhouses on the heights to the east, built in the fall of 1754 and the spring of 1755. Pattee owned and lived in one of these blockhouses, and in 1775 at least one town meeting was held there. Later, Kingsbury said, Pattee moved the blockhouse “to his farm down the river.”

Pattee was trading out of the former Fort Halifax longhouse, called the Fort house, “before the revolution,” Kingsbury said. Kingsbury listed his merchandise as including nails, blankets and the rum and molasses so ubiquitous in early mercantile accounts.

Whittemore called Pattee Winslow’s “pioneer innkeeper.” Pattee’s youngest daughter, Elizabeth (1777-1866), told Kingsbury that Pattee also ran a tavern in the old fort, entertaining many guests from Boston and at one time, Aaron Burr.

(Burr, now best remembered as Thomas Jefferson’s first-term vice-president [1801-1805] and as the man who killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel on July 11, 1804, was also a Revolutionary War soldier. His first assignment was with Arnold’s Québec expedition; whether this was the occasion Elizabeth Pattee meant or whether he came back to the Kennebec later, your writer does not venture to guess.)

Returns of the Fifth Regiment of the First Brigade, in 1792, commanded by Colonel Ezekiel Pattee.

By the time the July 8, 1776, town meeting convened, Winslow’s treasury was empty, and the Massachusetts government was requiring every town to collect ammunition and, evidently, to build a place to store it safely. Voters decided to borrow shingles and clapboards from half a dozen residents, with Pattee’s loan of 100,000 shingles the most generous.

Pattee was not on Winslow’s first Committee of Safety in 1776, but Whittemore wrote that he was among those who served on later “Committees of Correspondence, Inspection and Safety.”

(After British rule collapsed, leading citizens in most towns formed these committees to fill the vacuum. Duties included communicating and cooperating with other towns; supporting the war effort and suppressing Tories; and creating and enforcing local regulations and ordinances and doing other necessary tasks to keep town government running.)

When wandering groups of impoverished native Americans showed up in Winslow, it was “Squire Pattee” who fed them. At one point, Whittemore said, the town voted to pay him $5 a pound for 1,000 pounds of beef for this purpose.

In 1783, Pattee was chosen Winslow’s second representative to the Massachusetts legislature (Zimri Haywood was the first, in May 1782). Whittemore’s list of representatives says Pattee served in 1783 and 1784 and in 1786 and 1787; the town had no representative in Boston in 1785.

In 1787, Kingsbury said, Winslow chose Pattee and James Stackpole to join Capt. Denes (or Dennis) Getchell, of Vassalboro, to survey and mark the boundary line between the two towns.

When the first town church committee was elected at a Feb. 10, 1794, town meeting, Pattee was on it. Sources differ on the size and assignment of this committee. It and/or a separate committee had at least two responsibilities: to oversee building a meeting house, started in 1795 and finished in 1797; and to organize the June 10, 1795, ordination of Winslow’s first resident minister, Rev. Joshua Cushman.

Kingsbury wrote that Pattee “gave the burying ground on the river road, in which his body now lies.” He died Nov. 24, 1813, aged 81, and is buried in Winslow’s Howard cemetery.

Nearby are the graves of his wife Margaret and nine other Pattees. They include first son, Samuel, who died in 1783; second son, Lieutenant Benjamin (1762-1830), and Benjamin’s wife, Huldah (Dawes) (1766-1832); third son, William (1765-1795) and his wife, Sybil (Parker) (1772-1861), whom he married the year he died; oldest daughter Sarah (1767-1772); a daughter named Margaret W., who died July 29, 1807, at the age of nine years and whose name is not on other Find a Grave lists; and a granddaughter (?), Mary E., (1804-1901).

Also buried in the Howard cemetery is Colonel Josiah Hayden (see the Jan. 11, 2024, issue of The Town Line).

The Howard Cemetery is on the west side of Route 201 (Augusta Road), on the east side of the Kennebec River, about 0.6 miles south of the Carter Memorial Drive intersection and about 0.2 miles south of Drummond cemetery, on the west side of the road (mentioned in the Jan. 4, 2024, issue of The Town Line).

Pattee Pond in Winslow has an area of 712 acres and a maximum depth of 27 feet, according to a state Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife website (last updated in 2000). The Lake Stewards of Maine website agrees on the maximum depth, but reduces the size to 523 acres.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous.