Map of Vassalboro in 1879.

Going north from Augusta on Route 201 on the east bank of the Kennebec River, one follows the approximate route of Massachusetts Governor William Shirley’s 1754 military road between Fort Western, in present-day Augusta, and Fort Halifax, in present-day Winslow.

The town between Augusta and Winslow has been named Vassalboro since 1771, though the spelling has been simplified: Vassalborough lost its last three letters in the town clerks’ record books by 1818, according to local historian Alma Pierce Robbins.

Robbins starts her history in early March 1629, when England’s King Charles gave a group of men called the Massachusetts Company in London (or the Massachusetts Bay Company; sources differ) a charter for a Massachusetts colony. Among these men were Samuel and William Vassall or Vassal. In June, the company sent out three ships, which arrived in Salem on June 29, 1629.

Samuel (1586-1667; “probably” died in Massachusetts) and William (1590 or 1592 – 1656) were sons of a London Alderman (city councilman) named John Vassall (originally DuVassall), “a Protestant refugee from France.” In 1609, John Vassall became one of the Virginia Company chartered in 1606 by King James I – and, Robbins wrote, thereby determined that a piece of the Kennebec River valley would be named Vassalboro.

Robbins summarized the family’s ventures in England, Barbados and, to a much lesser extent, North America. William Vassall was briefly in Massachusetts in 1629, and from 1635 to 1648 lived in Scituate with his wife and six children.

Some later Vassalls moved permanently to Massachusetts, Robbins wrote. One of importance to Vassalboro was Florentius. According to Robbins, Florentius was Samuel’s great-grandson: Samuel had a son named John and John had a son named William, father of Florentius.

On-line sources, however, list one Florentius Vassall as a Jamaican sugar planter who married Anna Maria Hering Mill (born c. 1675), by whom he had a son, Florentius (1709-1776; called Florentius II in one source) before he died in 1712.

Another Florentius Vassal(l) was born around 1689 and died in 1778.

Two sources say Florentius II married Mary Foster, born in 1713; they had a daughter, Elizabeth (Vassal) Barrington, and/or a son, Richard (1732-1785 or 1795).

Robbins wrote that the Florentius Vassall who was William’s son and who was born in 1709 was one of the 1749 Proprietors of the Kennebec Purchase. She said he acquired acreage on both sides of the Kennebec from Pownalborough north, including in present-day Augusta and Vassalboro.

James North’s 1870 history of Augusta says the Florentius Vassall who was a Proprietor was son of William and great-grandson of Samuel.

This Florentius was born in Massachusetts, North wrote, where his father had come “as early as 1630,” but later moved to England and died in London in 1778 (not 1776). He had a son named Richard, and in his 1777 will left his land-holdings to Richard’s daughter Elizabeth’s male heirs, touching off title disputes that North said were finally settled by “the Supreme Court at Washington.” He gave no date; Robbins’ history suggests the Supreme Court was involved around 1850.

Robbins listed no Vassall among the early settlers in Vassalboro. The only mention of the family in the latter half of the 1700s is her account of a 1766 petition from the settlers to the Kennebec Proprietors asking for a grist mill at Seven Mile Brook, in southern Vassalboro.

Robbins commented that the petition was unusual in that it was sent to the whole company rather than to the individual Proprietor. Other Proprietors, she said, had built mills and churches for their settlers.

She added, “There is nothing to indicate that Vassall hastened to see that the inhabitants had a grist mill.”

(They did get one, and a sawmill as well, as described in the Jan. 11, 2024, article on mills on Seven Mile Brook.)

The 1761 Nathan Winslow survey, mentioned in previous articles, increased interest in Vassalboro land. Nonetheless, there were only 10 families living there in 1768; and remember, the town then extended 15 miles back from each bank of the Kennebec. The town was incorporated as Vassalborough on April 26, 1771.

Robbins credits the choice of name to Florentius Vassall’s “speculative [and profitable] deals in real estate” on this part of the Kennebec.

Henry Kingsbury, in his Kennebec County history, wrote that Vassalboro’s town records from 1771 to “the present” (1792) “are in four leather-bound books, well preserved and beautifully written.”

On May 17, 1771, Kingsbury said, Justice of the Peace James Howard (presumably the Fort Western James Howard) called the first town meeting, at “James Bacon’s inn.” Meetings were held in inns on alternate sides of the Kennebec for more than 20 years; the first town meeting house was authorized in 1795, on the east side of the river.

According to Kingsbury, the first “buildings” Vassalboro taxpayers paid for were two town pounds. He named the owners of the lots where they were built, but did not say where the lots were. He did write that the inhabitants were ordered to meet to build them in December, 1771, and anyone (presumably, any able-bodied man) who did not show up was fined.

Kingsbury described the first reference to schooling as a decision at the March 1790 town meeting to create nine school districts on the east side of the river. Less than two years later, on Jan. 30, 1792, Sidney, on the west side, was separated from Vassalboro and incorporated as a separate town. Readers will hear more about Sidney in a later article in this series.

* * * * * *

Winslow is the next town north of Vassalboro on the east bank of the Kennebec. It, like Vassalboro, started on both banks of the river and lost its western part, in its case in 1802.

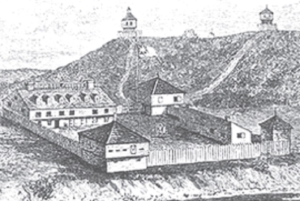

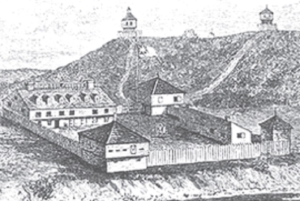

Fort Halifax in 1754.

Fort Halifax, built in 1754 (and mentioned in last week’s article) was not the earliest European building within the town boundaries. Kingsbury explained in his chapter on Winslow that the location, at the junction of the Sebasticook and Kennebec rivers, was important to Natives and Europeans, because rivers were main travel routes.

Kingsbury used the spelling Ticonic for the junction and for the falls upriver on the Kennebec. Edwin Carey Whittemore and Stephen Plocher, two writers of Waterville history, chose Teconnet; Plocher said the falls were named after Chief Teconnet. Early British records used Taconnett.

Kingsbury wrote that the first trader up the Kennebec, in 1625, was Edward Winslow, who might not have come as far as “the land that was destined to carry his named down to posterity.” On Sept. 10, 1653, according to a document Kingsbury quoted, Christopher Lawson built a trading house on the south side of the Sebasticook where the rivers joined.

In the same year, Kingsbury wrote, Lawson “assigned” his building to Clark & Lake (Thomas Clark or Clarke and Thomas Lake). Clark & Lake and Richard Hammond both had trading posts at Ticonic (and farther downriver) by 1675, when the Natives captured the Ticonic posts and apparently controlled the area until, Plocher wrote, the remaining building “was burned” – presumably by Europeans – in 1692.

Plocher called Hammond Winslow’s first white resident. Multiple sources say he was accused of cheating the Natives in his trading; they killed him in 1676.

As summarized last week, in 1754 Massachusetts Governor William Shirley had Fort Western built at Cushnoc and Fort Halifax built at Ticonic for protection against the French and their Native allies.

After Shirley and the Kennebec Proprietors agreed, on April 17, 1754, to build the two forts, the governor named General John Winslow, from Marshfield, Massachusetts, to supervise building Fort Western. Winslow (1703 -1774) was the great-grandson of Edward Winslow (1595 – 1655), who came to North America in 1620 on the Mayflower, was a governor of the Plymouth Colony and founded Marshfield.

Governor Shirley went up the Kennebec and personally chose the site for the fort, on the north side of the Kennebec-Sebasticook junction, as a strategic location to cut off Native communications and from which to launch an attack upriver.

Captain William Lithgow was the fort’s first commander, arriving on Sept. 3, 1754. Lithgow Street in present-day Winslow runs parallel to the Kennebec south of the rivers’ junction.

The fort’s name honored the Earl of Halifax. Kingsbury said he was the British Secretary of State. Louis Hatch, in his Maine history, said Halifax was President of the British Board of Trade, and added he was “sometimes called on account of his services to American commerce the ‘Father of the Colonies.'”

A settlement developed around the fort. Morris Fling, in 1764, was the first to farm the flat land nearby, Kingsbury said; the name “Fling’s Interval” lasted a couple generations.

Captain Lithgow used to have the river ice swept so his men could “slide the ladies,” Kingsbury wrote. A former island below the falls was a recreation area for Fort Halifax “officers and their families,” and a Native camping site as late as 1880.

Kingsbury also mentioned a brook named after a Sergeant Segar, who built a bridge crossing it. A contemporary on-line map of Winslow shows Segar Brk Avenue, off Whipple Street, north of Halifax Street (Route 100).

Plocher wrote the area’s first incorporation was as the plantation of Kingfield; Kingsbury called it Kingsfield; neither provided a date. It became the town of Winslow on April 26, 1771, including present-day Waterville and Oakland, named after General Winslow.

An on-line genealogy related to the historic Winslow house in Marshfield says Edward Winslow frequently voyaged between Massachusetts and England. He “died at sea somewhere in the Caribbean in 1655 while serving as Chief Civil Commissioner during the British fleet’s expedition to conquer the West Indies.” This information, in your writer’s opinion, increases the probability that General Winslow’s great-grandfather was the same Edward Winslow who Kingsbury said traded up the Kennebec in 1625.

Winslow’s first town meeting, Kingsbury said, was held at Fort Halifax on Thursday, May 23, 1771. In 1787, he wrote, Ezekiel Pattee (an early settler) and James Stackpole, of Winslow, and Captain Denes (or Dennis) Getchell, of Vassalboro, settled the Winslow/Vassalboro town line.

(Pattee was featured in the Jan. 25 issue of The Town Line as the man for whom Winslow’s Pattee Pond was probably named.)

Managing town business became increasingly difficult by the 1790s, especially since there was no bridge across the Kennebec. In 1793, Whittemore wrote, voters appointed two (tax?) collectors, one for each side of the river, and provided for preaching and town meetings to alternate between east and west banks.

After much discussion of a division, usually with the Kennebec as the dividing line (“though once a line one mile west of the river was proposed,” Kingsbury wrote), on Dec. 28, 1801, voters approved a petition to the Massachusetts legislature to make a separate town named Waterville on the west side of the river. The legislature approved June 23, 1802.

Main sources

Hatch, Louis Clinton, ed., Maine: A History 1919 ((facsimile, 1974).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Plocher, Stephen, Colby College Class of 2007 A Short History of Waterville, Maine Found on the web at Waterville-maine.gov.

Robbins, Alma Pierce History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous.