Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Natural resources – Part 4

/0 Comments/in Augusta, Local History, Maine History, Vassalboro/by Mary Grow

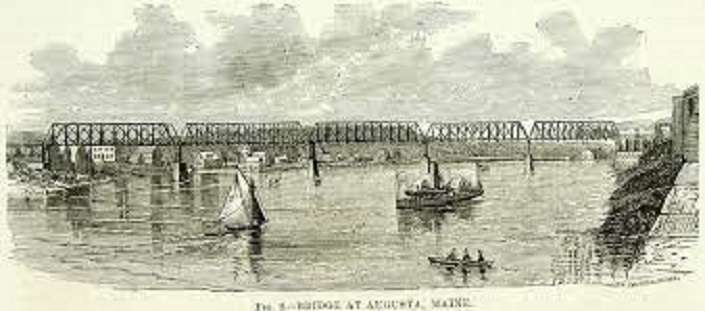

An 1837 wood etching of the railroad bridge crossing the Kennebec River. The bridge sat on granite pillars.

by Mary Grow

Augusta granite industry

“Augusta has been abundantly supplied…with the best of granite, easily quarried, and of convenient access,” Augusta historian James North wrote. He expressed surprise that the resource was not developed earlier; not only did the workers on the 1797 Kennebec bridge and the 1808 jail use boulders instead, but, he wrote, three gentlemen who built houses in the first decade of the 1800s brought granite for the foundations from the Boston area, “at great expense.”

One entrepreneur used Augusta granite beginning in 1825. However, North said when the State House was built in 1832 the granite came from Hallowell, in blocks “twenty-one feet long and nearly four feet square.”

In 1836, North wrote, three new granite companies were organized to develop Augusta’s deposits.

The Augusta and New York Granite Company planned to exploit the “Hamlen ledge,” about two miles out Western Avenue from the Kennebec. The Augusta and Philadelphia Granite Company focused on the “Ballard ledge,” about a mile and a half out Northern Avenue from the west end of the Kennebec bridge. The Augusta Blue Ledge Company bought “Hall’s ledge” across the river, about two and a half miles from the east end of the bridge via the North Belfast Road (today’s Routes 202 and 3).

There were also the “Thwing ledge” and the “Rowell ledge,” which North wrote were “a continuation of the Ballard ledge” that “cropped out of the neighboring hills.”

Kingsbury added later granite companies just outside Augusta, the Hallowell Granite Company (1871) and the Hallowell Granite Works (1885). Both were organized and led by Joseph Robinson Bodwell (June 18, 1818 – Dec. 15, 1887) of Hallowell, who was elected governor of Maine in 1887 and died during his first year in office.

Hallowell granite was famous for its high quality – “white, free working and soft, and can be almost as delicately chiselled as marble,” Kingsbury wrote.

In 1884, Kingsbury wrote, Joseph Archie started the Central Granite Company, in Manchester, whence came the granite for the 1891-92 “extension of the state house.”

Other central Kennebec Valley towns had deposits of granite, slate and probably other useful forms of stone, though mention in local histories is scant. Kingsbury said granite was the type of stone underlying farmland in towns as far apart as Albion and Windsor, but he did not write about quarries.

In Vassalboro, Alma Pierce Robbins wrote, the 1850 census had a summary paragraph on the town’s amenities, including pure water, timber, natural fertilizer (“swamp muck hauled into yards in summer and in one year it proves about equal to stable manure”) and “rocks, granite and slate.”

Sidney also had slate deposits that were worked, Robbins said. She quoted a source saying that in 1837, Sidney slate cost $8 a ton, versus $27 a ton for slate imported from England.

* * * * * *

Last week’s article mentioned Augusta’s first bridge across the Kennebec, built in 1797. North described the construction.

The initial project cost was $15,000, he wrote; local people contributed, but could not have started without help from Massachusetts-based landholders and others, including a man named Leonard Jarvis, “owner of lands beyond the Penobscot.”

(This Leonard Jarvis would have been too young to be the Leonard Jarvis [1781-1854] of Surry, Maine, Harvard Class of 1800, Hancock County sheriff, representative to Congress 1829-1837. However, bridge investor Jarvis might have been the Leonard Jarvis [your writer found no dates] who, with Samuel Phillips and John Read, sold the Bingham Purchase, two million acres of Maine land bought by William Bingham, of Philadelphia, in early 1793. This Leonard Jarvis was in correspondence with Daniel Cony, a prominent Augusta resident, in the 1790s.)

An architect North called Captain Boynton designed the bridge. Work started on May 5, 1797, only two months after Augusta separated from Hallowell. The wooden foundation, forty feet square, supported on its timber floor the bridge pier, described as “stone walls [North said “granite” in the next sentence] nine feet thick, forming on the inside an oval or egg-shaped opening.”

This stage of construction was finished Sept. 9, 1797, and followed by a public celebration. Next, the abutments were built, also of stone, and then the superstructure. North observed that, “The granite used for the masonry was obtained from boulders, the stratified granite so abundantly quarried at the present day being them unknown.”

The whole “very graceful and elegant” bridge was finished Nov. 21, and there was another celebration, a dinner shared by the incorporators, the workmen and residents. Citing midwife Martha Ballard’s diary, North wrote that “Cannon were fired responsive to toasts given, and David Wall, James Savage and Asa Fletcher who were managing the gun were injured by some of the cartridges taking fire.”

(If your writer found the right James Savage on line, his injuries were not fatal. Born June 5, 1775, in Augusta, he married Eliza Bickford on Feb. 21, 1822, in New Hampshire; on Nov. 11, 1826, became father of a son, also named James; and died Jan. 27, 1865, in an unknown location.)

The bridge was a covered bridge, as were almost all 19th-century bridges crossing the Kennebec. In his Kennebec Yesterdays, Ernest Marriner explained that covering was “to protect the timbers from weather,” so they wouldn’t rot so fast.

North wrote that the final cost of the bridge was $27,000. The stockholders paid off the debt with income from tolls; not until eight years later did they get their first dividend.

Because the 1797 Augusta bridge was the first bridge across the Kennebec (and “the greatest enterprise of the kind yet undertaken in the District of Maine”), nearby towns on both sides of the river laid out roads to lead to it, promoting Augusta’s growth.

This bridge collapsed, noisily but without killing anyone, the afternoon of Sunday, June 23, 1816. North wrote that a ferry, pulled on a rope, ran back and forth until a new bridge opened two years later.

The new bridge, opened in August 1818, served until it burned in 1827. North, amply quoting from a source he did not list, gave one of his more dramatic descriptions.

The fire started a little after 11 p.m., Monday, April 2, he said. First seen “bursting through the roof,” soon “the flames were fanned into the wildest fury, and with a ‘tremendous roaring,’ in a dense and waving mass high above the water, spanned the river from shore to shore, capped by rolling clouds of black smoke.”

After the flammable covering over the bridge burned away, “a magnificent spectacle appeared of a bridge with a framework of fire,” each piece of the structure outlined in flames. The debris fell into the Kennebec, in two pieces, and floated downriver, still burning.

North wrote that the tollkeeper’s wife was badly burned as she tried to run away. Stores on both banks of the river were damaged; residents on the east bank, including “ladies who worked with great coolness and energy” passing buckets of water up from the river, saved two stores there.

Hallowell sent two fire engines, but “owing to the bad state of the roads” the worst was over by the time they arrived. North estimated losses at $16,000, with almost nothing insured.

Arson was first suspected, because a man had been seen “lurking around the bridge” shortly before the fire. The final consensus was the cause was accidental, “probably from a lighted cigar thrown upon the flooring.”

Reconstruction began promptly, supervised by Ephraim Ballard, Martha Ballard’s husband. North wrote that the first people on foot crossed the successor bridge on Aug. 3 and the first carriages on Aug. 18, 138 days after the fire. The 1827 bridge was still in use in 1870.

This Kennebec bridge was a toll bridge, bringing income to its owners but annoying residents. The first attempt at a free river crossing was a legislative act March 23, 1838, authorizing a group of citizens (one was named James Bridge) to build another bridge within 10 rods north of the Kennebec Bridge and to buy the Kennebec Bridge. The group failed to raise enough money.

Voters at the 1847 town meeting appointed a committee of town officials to ask the Kennebec Bridge owners about renting or buying the bridge and to get a cost estimate for free ferry service from the town landing. Talks failed, as did renewed discussion the next year, and a seasonal subscription-supported ferry “was too expensive to be long continued.”

New bridges at Gardiner and then Hallowell kept discussion going, and on April 15, 1857, the legislature approved a charter for the Augusta Free Bridge Company. It was authorized to try to buy the Kennebec Bridge and, if no agreement could be reached, to build a new bridge.

Company stockholders could use the new bridge for free; the first plan was that everyone else would pay tolls until the cost of the new bridge was recouped and a $15,000 maintenance fund built up. North summarized a great deal more discussion, with Augusta city officials getting involved. With municipal financial backing, on July 1, 1867, the bridge across the Kennebec at Augusta became a free bridge.

* * * * * *

An unusual resource found in some Kennebec Valley towns was bog ore or bog iron, a naturally occurring material that can be transformed into useable iron.

Wikipedia calls bog iron “a form of impure iron deposit that develops in bogs or swamps by the chemical or biochemical oxidation of iron.” The iron is unearthed by groundwater, oxidized in the atmosphere and carried into the swamp; “bog ores consist primarily of iron oxyhydroxides, commonly goethite (FeO(OH)).”

Conditions making iron bogs possible include “local geology, parent rock mineralogy, ground-water composition, and geochemically active microbes & plants,” Wikipedia says. Bog iron is considered a renewable resource; a bog “can be harvested about once each generation.”

Bog iron can be purified without melting it, Wikipedia says, and humans have been using it since pre-Roman times. Vikings are mentioned as major users, and the article says the presence of bog iron seems to have been one factor that influenced Vikings’ choice of settlements in North America. Bog iron was turned into iron ore at the well-known Viking site at L’Anse aux Meadows, in Newfoundland.

Later European settlers developed the resource extensively in Virginia, beginning in 1608; Massachusetts, from the 1630s; and New Jersey before the Revolution – Wikipedia says New Jersey made bog-iron cannonballs for the American army.

Again, local histories are not filled with information on bog iron. Two sources, however, document two different workings in Clinton.

The earlier of the two was “at the mouth of the fifteen mile stream, on the Kennebec,” according to North. He wrote that because the 1807 embargo cut off iron imports, by 1808 Jonathan B. Cobb was making iron from bog ore at his forge there. North mentioned it in his Augusta history because Cobb advertised in the Feb. 16, 1808, Kennebec Gazette offering bar iron, mill cranks and plough and crowbar moulds.

Kingsbury wrote that sometime before 1824 a Mr. Peavy set up a forge near Carrabassett Stream, which flows into the Kennebec at Pishon’s Ferry, opposite Hinckley, in Fairfield. There he “made iron out of bog ore obtained on the spot.” The forge was closed by 1826, Kingsbury wrote, but its remains could still be seen in 1892.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Website, miscellaneous.

SCORES & OUTDOORS: Swans are sighted on west shore of Webber Pond

/0 Comments/in Scores & Outdoors, Vassalboro/by Roland D. Hallee by Roland D. Hallee

by Roland D. Hallee

It has been reported that a bevy of swans has been spotted on Webber Pond. Interesting. So I had to investigate. Oh, by the way, a bevy of swans is when they are on the ground. While in flight they are called a wedge.

The swan is known around the world for its beauty, elegance, and grace.

The swan has the ability to swim and fly with incredible speed and agility. This bird is also very intelligent, devoted to its mate, and highly aggressive about defending its young. They are a common sight in temperate and colder climates around the globe.

The English word “swan” is also shared with the German and Dutch. It likely has its roots in the older Indo-European word swen, which means to sound or to sing.

This bird is much faster on land than you might suspect with speeds of 22 miles an hour. In the water, it can also achieve speeds of around 1.6 miles per hour by paddling its webbed feet. But if they stretch out their wings, then swans can let the wind carry them at much higher speeds while also saving energy.

These birds feature prominently in human mythologies and arts around the world. Some of the most famous stories involve metamorphosis and transformation. A Greek legend claims that the god Zeus once disguised himself as a swan. The famous 19th century Tchaikovsky ballet Swan Lake, which derived from Russian and German folk tales, is the story of a princess transformed into a swan by a curse. And of course, the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale The Ugly Duckling is about a duck that transforms into a swan.

Swimming gracefully through the water, these birds are an impressive spectacle whose characteristics include a large body, a long and curved neck, and big feet. Each species has different colored plumage. The common mute swan is almost completely covered in white feathers except for an orange bill and some black markings on the face.

These birds rank as the largest waterfowl and among the largest birds in the world.

Among these birds’ most remarkable social characteristics are the intense bonds they form with one mate for life. Unlike many other species of birds (even the closely related geese and duck), this has a few distinct advantages. First, it allows the pair to learn from their reproductive failures and develop better strategies. Second, the couple will share several duties, including the construction of nests, which they build out of grasses, branches, reeds, and other vegetation. This makes them far more effective than it would be on its own. Third, because of their long migratory routes, they have less time to acquire a mate, so the lifelong bond actually saves them time.

These birds are quite defensive animals that will do anything to protect their young. To drive off threats, they will engage in a display called busking, which involves hissing, snorting, and flapping with their outstretched wings. Due to their relatively weak bones, this display is largely a bluff that has little force behind it, but it doesn’t stop them from gloating. After driving off a predator, they make a triumphant sound. They also communicate through a variety of other vocalizations that emanate from the windpipe or the breastbone, including in some species a geese like honk. Even the so-called mute swan can make hissing, snoring, or grunting sounds.

After the breeding season, the bird migrates to warmer climates in the winter by flying in diagonal V formations with around 100 individuals. When the lead bird tires, another one takes its place at the front. These birds can be either partially migratory or wholly migratory depending on where they nest. The fully migratory species typically live in colder climates and may travel the same route thousands of miles every year toward warmer climates.

These birds are endemic to ponds, lakes, rivers, estuaries, and wetlands all over the world. Most species prefer temperate or Arctic climates and migrate during the colder seasons. The common mute swan is native to Europe. It was later introduced into North America (where it flourished).

Swans are omnivores, meaning they eat both plants and other animals. When swimming in the water, it feeds via a method called dabbling in which it flips upside down and reaches down with its long neck to the vegetation at the bottom of the floor. The bird can also come up onto land in search of food.

These bird’s large size, fast speeds, flying ability, and rather aggressive behavior (at least when threatened) are a deterrent for most predators, but the old, ill, and young (especially the eggs) are sometimes preyed upon by foxes, raccoons, wolves, and other carnivorous mammals. Habitat loss, pollution, and overhunting have all posed a persistent threat, but they can adapt quite well to human habitations, and the cultivation of ponds and lakes for local wildlife has kept population numbers high. In the future, swan habitat and migratory patterns will be affected by climate change.

Thanks to years of protection, the swan genus as a whole are in excellent health. According to the IUCN Red List, which tracks the population status of many animals around the world, every single species of the swan is listed as least concern, which is the best possible conservation prognosis. Population numbers, though not known with precise accuracy, appear to be stable or increasing around the world. The trumpeter swan endemic to North America once fell to as little as 100 birds in 1935, but it has since been rehabilitated.

Swans have symbolized different things to different people. They were a symbol of religious piety in ancient Greece. They were revered for their purity and saintliness in Hinduism. And because of their lifelong bonds, they’ve also symbolized love and devotion around the world.

The common phrase “swan song,” which means a mournful call at the moment of the swan’s death, appears to be a myth. It is still regularly used in modern English to signify a final graceful exit, but the origin of this belief is not well understood. According to the author Jeremy Mynott, who wrote a book about birds in the ancient world, the phrase might have to do with the swan’s connection to Apollo, the god of prophecy and music. The philosopher Plato believed that the swan song was a “metaphorical celebration of the life to come.” Rather than bewailing their own deaths, Plato writes, the swans are “happy in the knowledge that they are departing this life to join the god they serve.” Other ancient authors were skeptical of the swan song and sought to debunk it. More recently, some scientists have tried to find a more rational and scientific explanation for this belief, but more likely it’s based entirely on symbolism and myth.

Despite their intense devotion to each other, swans do not die from grief. This appears to be a myth derived from a dubious ancient source. If a mate dies prematurely, then the surviving swan will usually find a new mate. What they feel after a mate dies is not entirely clear, since we cannot know fully what they are thinking.

Roland’s trivia question of the week:

Which shortstop’s league-leading 209 hits helped him win the 1997 rookie of the year award?

Vassalboro nomination papers available

/0 Comments/in News, Vassalboro/by Website Editor Nomination papers for the November Election will be available Monday, July 25, 2022, at the Vassalboro Town Clerks office. Candidates for office must obtain at least 25 certified signatures to qualify for placement on the November 8, 2022, ballot. The following position is available:

Nomination papers for the November Election will be available Monday, July 25, 2022, at the Vassalboro Town Clerks office. Candidates for office must obtain at least 25 certified signatures to qualify for placement on the November 8, 2022, ballot. The following position is available:

- Kennebec Water District Trustee (3 year term)

All nomination papers must be returned to the clerk’s office by 12:00 p.m. (noon), September 9, 2022.

China planners agree with many solar ordinance changes

/0 Comments/in News, Vassalboro/by Mary Grow by Mary Grow

by Mary Grow

The three China Planning Board members participating in the July 12 meeting agreed with many of Board Chairman Scott Rollins’ proposed changes in the draft Solar Array Ordinance. They scheduled others for discussion at July 19 and July 26 board meetings and at a public hearing set for 6:30 p.m. Thursday, Aug. 4, with final decisions at the board’s Aug. 9 meeting.

Rollins’ goal is to present the Solar Array Ordinance, and proposed changes to two parts of the existing Land Use Ordinance, to China Select Board members at their Aug. 15 meeting. Select board members could accept the documents for inclusion in a Nov. 8 local ballot; or, if they ask for clarifications or changes, planners could re-review on Aug. 23 and resubmit to select board members on Aug. 29.

The draft solar ordinance distinguishes between commercial developments, as a principal use of a piece of land, and auxiliary arrays, ground-mounted or on roof-tops, usually intended to power a single house or business. It categorizes arrays by size, small, medium or large.

It imposes stricter limits on solar development in shoreland, stream protection and resource protection areas than in rural areas. Depending on the type of solar array and the location, either the codes officer or the planning board is empowered to review an application.

One issue left for future discussion was what types and sizes of solar development should be allowed in protected areas, and what type of review to require.

Another was how to guarantee that after a commercial solar development reaches the end of its useful life, the infrastructure will be removed and the land restored to its previous state. The question began as how to hold the developer responsible; board member Walter Bennett added that the landowner from whom the developer leased the area should also have responsibility.

Commercial solar arrays are routinely fenced to keep trespassers out. Based on their visit to an operating solar farm on Route 32 North (Vassalboro Road), board members want the ordinance to include provisions ensuring wildlife movement. At the same time, they want the solar company to be able to protect its property. Options discussed included elevating the bottom of fencing around the development so small animals can get under, leaving gaps in fences, or – especially for a large project – fencing separate sections with passages between.

The conclusion was that wildlife passage will be required, with methods appropriate to each site to be negotiated with the developer.

Audience member Brent Chesley recommended a specific change in the draft ordinance. It currently says that building owners may add solar equipment to their buildings “by right” unless both the codes officer and the local fire chief find the addition would create an “unreasonable” safety risk.

Pointing out that the codes officer and the fire chief look at different issues, Chesley recommended changing “and” to “or.” Planning board members agreed.

The May 2021 draft of the solar ordinance is on the Town of China website, china.govoffice.com, under the planning board heading. An updated version is to be posted as soon as possible after the July 26 board meeting for residents’ review before the Aug. 4 public meeting.

Planning board meetings are held at 6:30 p.m., usually in the town office meeting room, and are open to the public, in person and via LiveStream.

Vassalboro select board tackles three big projects

/0 Comments/in News, Vassalboro/by Mary Grow by Mary Grow

by Mary Grow

Vassalboro select board members had three big projects on the agenda for discussion at their July 14 and future meetings, and resident Tom Richards proposed an even bigger fourth one.

Board chairman Barbara Redmond has been working on a draft solar ordinance, as requested by a majority of the voters who answered a non-binding question at the polls June 14. She asked for more suggestions before the draft is ready for review by the town attorney.

Redmond hopes to have an ordinance ready to present to voters on Nov. 8.

(China Planning Board members hope to present a solar ordinance to China voters on Nov. 8. According to the Town of Windsor website, Windsor Planning Board members are working on an ordinance on solar farms.)

Conservation Commission members Holly Weidner and Peggy Horner presented two proposals, to develop the new park on Outlet Stream and to try to make Vassalboro eligible for a new state grant program.

Weidner said the park proposal, on town-acquired land between East and North Vassalboro, envisions a parking lot big enough for six cars off Route 32, a crushed stone path to the stream, small fishing platforms of stone or wood on the bank and picnic tables. Vassalboro voters appropriated $20,000 for work at the park at their June 6 town meeting.

So far, Weidner said, the Vassalboro public works crew has cleared brush and removed some trees. The Conservation Commission has obtained a state highway entrance permit, and has filed an application with the state Department of Environmental Protection for work near the water.

A future issue is the extent of town maintenance, like mowing, renting a portable toilet and perhaps providing water from a well on the property. Depending on park uses, a pavilion or other shelter might be added. Weidner said the unofficial name of the property is Eagle Park, because so many eagles, ospreys and great blue herons congregate, especially when alewives are running.

Select board members encouraged Conservation Commission members to proceed.

Horner explained briefly the potential advantages of Vassalboro’s participating in the program from the Maine Governor’s Office of Policy Innovation and the Future, called Community Resilience Partnership (CRP).

The goal is to prepare Maine municipalities for effects of climate change. CRP provides “direction and grants” (from $5,000 to $50,000) to support projects that “reduce greenhouse gas emissions and make communities more resilient to the impacts of climate change.”

The application process requires a self-evaluation of potential hazards and ways to try to mitigate them and choosing from a long list of possible projects, followed by a “community workshop” to review the evaluation and prioritize the projects. Horner said the Conservation Commission cannot do the evaluation; she suggested a small group of well-informed residents could put it together in a few hours.

Town Manager Mary Sabins’ reaction was, “Why not?” Select board members agreed trying to make a fall 2022 grant application deadline was not realistic; the spring 2023 round would be more feasible.

More information is on the CRP website, Maine.gov/future/climate/community-resilience-partnership.

Richards proposed that town officials look into acquiring and replacing the bridge over Seven Mile Stream on Cushnoc Road, the southernmost section of old Route 201 (Riverside Drive). State officials have limited loads on the state-owned bridge to the point where Vassalboro’s larger public works trucks and fire trucks cannot use it and businesses using heavy equipment are inconvenienced.

There is no firm information on state intentions; the expectation among meeting participants was that the state will continue to reduce the weight limit and eventually close the bridge. Richards sees closure as a major safety issue for Cushnoc Road residents.

Sabins said an engineer had given an informal cost estimate, based on another similar project, of one million dollars.

Board members intend to carry on with just-retired chairman Robert Browne’s idea of a visioning/planning session, a special meeting to consider long-range, large-scale issues, and will likely have the CRP and perhaps the Cushnoc Road bridge on the agenda. The special meeting is tentatively to be in October.

Also postponed, perhaps to that meeting, was discussion of use of the rest of the town’s American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) money. Sabins’ figures show a balance of $463,206.05.

Board member Chris French asked whether the China Lake outlet dam needed work that ARPA funds might cover. Sabins replied that Maine’s dam inspector, Tony Fletcher, had looked at the dam recently and found no big issues.

Fletcher did recommend clearing grass from the top of part of the dam and putting in crushed stone, she said. The grassy area is in mid-stream; Sabins is confident the public works crew will find a way to move crushed stone out to it.

In other business July 14, in a series of unanimous decisions, select board members:

- Reappointed John Phillips as a planning board member (his name was accidentally omitted from the June 23 list) and appointed Kenneth Bowring to the Trails Committee and Daniel Bradstreet as the alternate planning board member.

- Authorized Road Foreman Gene Field to contract for this summer’s paving, with the understanding that if the budget cannot cover all proposed work, the end of Cook Hill Road will remain gravel.

- Waived the town procurement policy and authorized Field to negotiate with O’Connor Auto Park, in Augusta, for a new town public works truck, facing the possibility of a budget-busting price increase.

- Extended contracts with current trash haulers for a year, at higher prices, as expected and budgeted for.

- Reviewed, with appreciation, Transfer Station Manager George Hamar’s suggestions for a Quonset hut type covering for the new compactors at the transfer station, but postponed a decision.

Vassalboro select board members meet only once a month in July and August, instead of every other week. Their next regular meeting is scheduled for 6:30 p.m. Thursday, Aug. 11, in the town office meeting room.

VASSALBORO: Routine application turns into review of requirements

/0 Comments/in News, Vassalboro/by Mary Grow by Mary Grow

by Mary Grow

What started as a simple application to the Vassalboro Planning Board at the July 12 meeting turned into a review of application requirements, a topic board members intend to pursue.

They also approved the application, for Ashley Breau to open a Med Spa, at 909 Main Street, in North Vassalboro, in one of the two single-story buildings Ray Breton owns on the east side of the street.

Breton, representing Breau at the July 12 meeting, said she has a similar business in Topsham and plans to open another in southern Maine. A web search found Breau’s name as owner of CosMEDIX & Cryo MedSpa, at 127 Topsham Fair Mall Road. Services offered include “Face and body makeup, permanent makeup, dysport, Botox, Dysport injections.”

Breau’s business will be next door to Amber French’s eyelash extension business, approved by board members at their May 3 meeting. Breton said it is busy.

“Two businesses that I’ve never heard of before,” board chairman Virginia Brackett commented.

Because Breau’s business is moving into an existing building and she plans no construction or exterior changes, she had answered most questions about environmental and neighborhood effects on the application form with “N/A” (not applicable).

Board member and former codes officer Paul Mitnik objected that the answers were not adequate – the applicant should give explanatory information, and planning board members should use her information, not their own knowledge.

For example, the building now has no buffers – bushes or trees to control water run-off and screen the building from neighbors. Breau plans no change. Breton said there is no space for a buffer, because of the street in front, properties on both sides and the soccer field he has provided in back.

After discussion, the other members present agreed Mitnik was correct. They also agreed, and persuaded him, that Breau’s application should be approved based on their knowledge and Breton’s information.

Brackett and Codes Officer Ryan Paul then added a statement about the lack of space for buffers at 909 Main Street. Board members added other information.

In the future, Paul will give applicants more guidance on what information to provide. For example, board members said, the application should include a description of the nature of the business, proposed hours of operation and copies of any required state or other licenses.

Board members also talked about evidence of right to use the property (Breton said he does not sign leases with his tenants, and satisfied the requirement by writing a note saying he is letting Breau open her business in his building), parking plans and other information, partly in relation to a pending application that was not on the July 12 agenda.

That application, from Rosalind Waldron to open a medical office at 991 Main Street, was originally on the board’s June 7 agenda. Paul said it is now on the board’s Aug. 2 agenda. Brackett and other board members listed information that should be added to Waldron’s current draft.

Attending the July 12 meeting were new select board member Rick Denico, Jr., and Waterville codes enforcement officer Daniel Bradstreet, son of state Representative Richard Bradstreet, of Vassalboro. Denico participated in reappointing planning board members at his first select board meeting June 23. He said select board members would appoint Bradstreet the new alternate planning board member at their July 14 meeting; they did.

Denico said Vassalboro voters created the planning board at a March 7, 1957, town meeting. No one was aware of any charter, ordinance or other regulation, then or since. The state’s manual for planning board members is “very legalistic,” Denico commented.

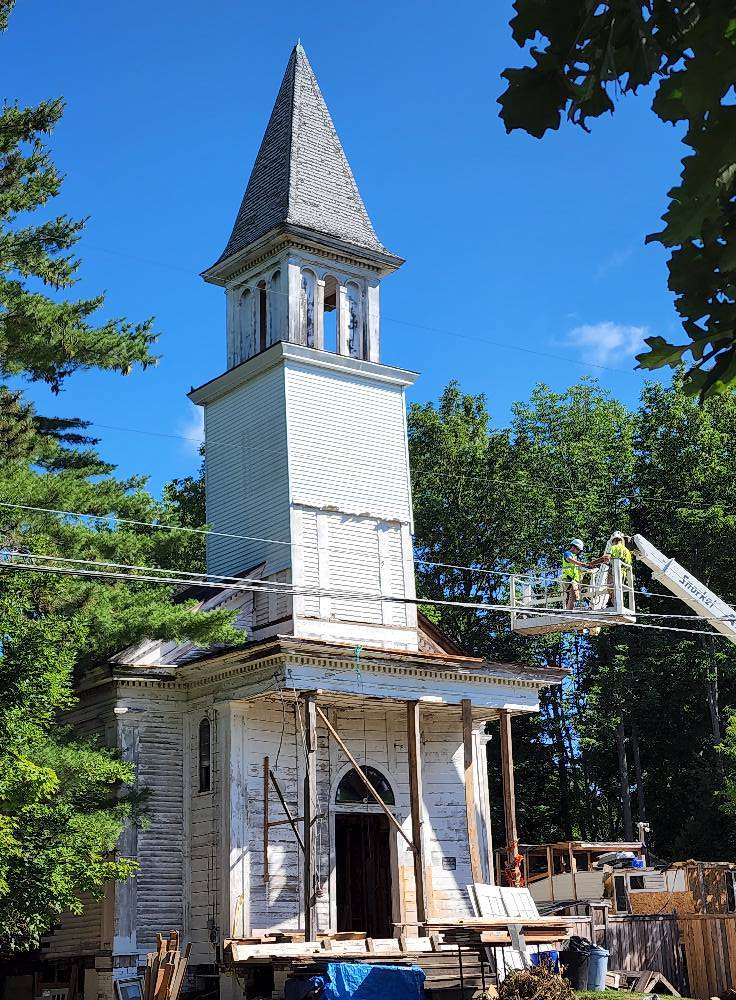

PHOTOS: Former Vassalboro Methodist Church is dismantled

/0 Comments/in Community, Local History, News, Vassalboro/by Website EditorNew exhibit at Vassalboro Historical Society depicts textiles

/0 Comments/in Community, Local History, Maine History, Vassalboro/by Mary Grow

Painting signed by Hedwig Collins. Eva (Pratt) Owen, headmistress at Oak Grove School from 1918 – 1958, front and center in a light blue gown and matching hat, holding a white shawl; her husband, headmaster Robert Everett Owen, under the trees at left in a dark suit, behind a young lady in red. The woman in purple hat coming down the lawn is said to be Mrs. Owen’s sister.

by Mary Grow

Photos courtesy of Jan Clowes, VHS president

The new display at the Vassalboro Historical Society (VHS) Museum in East Vassalboro is titled “All Things Textile,” and the name is appropriate.

The most eye-catching items are women’s dresses, from the early 1800s to the 1950s, in varied materials and colors, and on one wall a large painting of young ladies in spring outfits (and two gentlemen) gathered on the lawn of the Oak Grove School.

The gentleman in black, half hidden behind a bevy of students under the trees in the left of the painting, is identified as Headmaster Robert Owen. Front and center is his wife, Headmistress Eva (Pratt) Owen, wearing a light blue gown and matching flat hat. Behind and to her left, the woman in the purple dress and hat coming toward the viewer is said to be her sister, Edith (Pratt) Brown.

By the castle, on the right side of the painting, students greet an unidentified man on horseback.

The painting is signed by Hedwig Collin. Wikipedia identifies her as a Danish artist, born May 27, 1880, and known primarily as a writer and illustrator of children’s books. She also did portraits and landscape paintings, Wikipedia says, and another on-line site includes reproductions of fashion illustrations from different decades.

Collin spent World War II in the United States, and VHS President Jan Clowes says the Oak Grove painting is dated 1940. Collin died near Copenhagen, Denmark, on April 2, 1964.

The black dress is a walking suit from 1910. The red dress is a teenager’s from 1830 and the white wedding dress Mary C. Haynes designed and wore when she married John Bussell on June 13, 1953.

On other walls are three samplers stitched by young Vassalboro residents in 1816, 1821 and 1836. Shelves and display tables and cases contain a working sewing machine from the late 1870s, children’s clothing, men’s hats and shoes and other items. Two interactive stations let visitors test their skills by working on a hooked or a braided rug.

There is also an antique quilt frame that Clowes said is being raffled off as a fund-raiser for the Society.

The Society’s website says the display was put together with help from Textile Conservation Specialist Lynne Bassett, who is from Massachusetts. Her assistance to museum volunteers included identifying fabrics and estimating ages of items in the collection; advising on proper storage; and teaching volunteers four “conservation stitches” so they can do authentic repairs.

Bassett is scheduled to continue working with Society volunteers later in July. “We take care of things, and consult experts when we need to,” Clowes said.

Elsewhere in the building, visitors can enjoy replicas of a 1950s kitchen and a much earlier Native American encampment; view local artists’ work; and admire a collection of furniture, tableware and dozens of other items once used by Vassalboro families.

The Society’s library has an invaluable collection of letters, documents, books and other sources of information on past events in the town. The website credits volunteer Russell Smith for answering reference questions.

Other volunteers mentioned are Juliana Lyon, in charge, with Clowes, of organizing accession records; Ben Gidney, Stewart Carson, Jeremy Cloutier, Dawn Cates, Simone Antworth, Judy Goodrich, Steve and Sharon (Hopkins) Farrington and David Theriault; and specifically for the textile conservation project, Goodrich, Cates, Maurine Macomber, Theriault, Terry Curtis and Holly Weidner. More volunteers are always welcome, Clowes said.

Clowes also welcomes donations of local items, although she does not know where there will be room for them. Some families who have donated larger items are storing them for the Society, Clowes said.

This dress, part of the textile display, is a two-piece wedding dress, with a long train trimmed with lace. Annie Mae Pierce wore it when she married Henry Allen Priest on Aug. 31, 1880.

The next major project is acquiring a barn. In Clowes’ vision, it has two stories; generous space on the ground level will display farm equipment and similar large items, with smaller items above. Monetary donations toward the barn project, and to maintain the present building, are appreciated; the VHS is a non-profit organization and donations are tax-deductible as allowed by law.

The museum is in the former East Vassalboro Schoolhouse, at 327 Main Street, on the east side of Route 32, just north of the boat landing at the China Lake outlet. In one room, the old tin ceiling is visible, and the floors show the circles of screwholes where students’ chair-and-desk combinations were attached.

The VHS website is vassalborohistoricalsociety.org. The telephone number is 923-3505; the email address is vhspresident@gmail.com; and the mailing address is P. O. Box 13, North Vassalboro ME 04962. Regular open hours are Monday and Tuesday from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.

The summer and fall calendar includes open houses Sunday afternoons from 1 to 4 p.m., on July 24, Aug. 14 and 28, and Oct. 9 and 23.

Three special programs are scheduled for Sunday afternoons from 3 to 5 p.m.: on July 17, Sharon Hopkins Farrington, on “Rug Hooking Past & Present”; on Aug. 21, Nate Gray, on “River Herring Ecology & History”; and on Oct. 16, Suzy Griffiths, “Holman Day Film-Fest.”

In September, the museum will be open during the Vassalboro Days celebration Sept. 10 and 11. The annual meeting and potluck meal are scheduled for 5 p.m. Sunday, Sept. 25, at the East Vassalboro Grange Hall.

Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Natural resources – Part 2

/0 Comments/in Local History, Maine History, Vassalboro/by Website Editorby Mary Grow

Rocks & clay

Last week’s article talked about some of the towns in which European settlers found naturally-occurring resources, like stones and clay. Stones were described as useful for foundations, wells and similar purposes on land; another use was for the dams that have been mentioned repeatedly.

Palermo historian Milton Dowe, in his 1954 town history, said settlers coming to the area then called Great Pond Settlement (because it was near the head of Sheepscot Great Pond) in the late1770s lived in log houses until entrepreneurs built sawmills to make boards. The prerequisite for a sawmill, he wrote, was “a dam of rock and dirt on a brook of almost any size.”

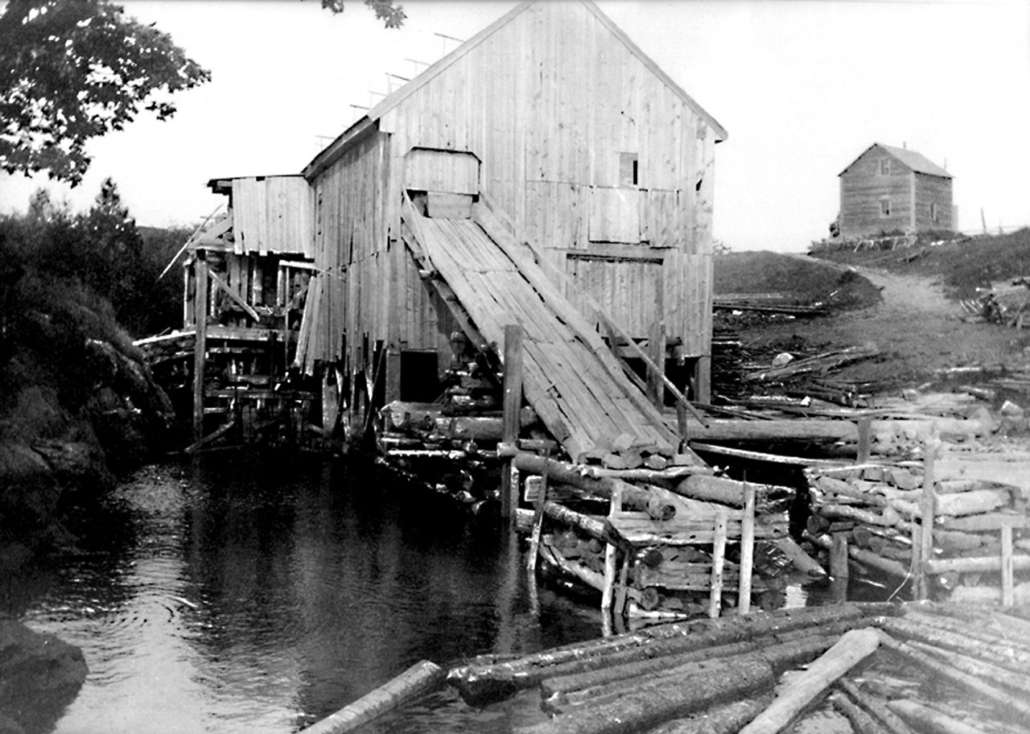

The majority of local histories describe early water-powered mills in Kennebec Valley towns, most built on streams (many of them tributaries to the Kennebec) before men had the courage to try to dam the larger river. Assuming a dam for each mill or cluster of mills, thousands of stones must have been moved.

In Vassalboro in the 1820s, according to an unnamed source quoted in Alma Pierce Robbins’ town history, there were “19 water powers,” presumably dams and presumably at least partly made of stone. Thirteen were on Outlet Stream, which flows north from China Lake through East and North Vassalboro to the Sebasticook; the other six were on Seven Mile Stream, Webber Pond’s outlet into the Kennebec.

Windsor historian Linwood Lowden described the agreement that allowed the building of an 1809 dam across the West Branch of the Sheepscot River, at Maxcy’s Mills, in Windsor. Cornelius Maguire and Joseph Linscott signed a 15-year lease allowing Joseph Bowman, from Gardiner, to dam the river and build a sawmill.

Bowman’s lease included land on each bank to anchor the dam, and “the right to as much gravel, dirt, timber or stones” as he needed, except he could not cut pine or oak. Other Windsor streams also had mills; the remains of some of the mill dams were visible in 1993, Lowden wrote.

Robbins and Dowe mentioned another use for stone: building bridges. Robbins found that an 1831 town meeting voted to build a stone bridge “near Jacob Southwick’s plaster mill.” In 1841, Dowe wrote, Palermo town meeting voters appointed a three-man committee to oversee construction of a 640-foot-long bridge “of stone covered with earth,” a four-year project.

Stone has multiple meanings, and historians seldom specify what size, shape or material they’re talking about. Stones interrupting plowing are not the same as the stone in Thomas Saban’s Palermo quarry “near the head of Sheepscot Lake” that Dowe described.

Dowe wrote: “Here the stone was found in layers of various thicknesses all standing on edge from the upheaval of the earth centuries ago. To obtain any size wanted the stone was drilled and wedged.” The two specific uses he cited were steps and well covers.

(Wikipedia provides engineering information on wedging. The process could work several ways. If the stone had natural cracks, steel wedges were hammered into the cracks to split the stone into desired sizes. If there were no cracks, the quarryman made some. He drilled a row of holes, into which he inserted conical wedges called plugs and flat wedges called feathers and hammered them; or, one source says, he put wooden plugs with the feathers and wetted the plugs so that they expanded and broke the stone.)

* * * * * *

Bricks, their production and uses, were the focus of last week’s article, and, as usual, your writer found more than a page’s worth of information, so this week’s installment will continue the topic.

Robbins tossed off a comment in her Vassalboro history, in a section on early settlers: “Bricks were a great business, developed almost as soon as the sawmills according to most histories of Maine. (The town records confirm this statement.)”

There were several brickyards in Palermo, Dowe said. One, not long after 1800, was on the Marden brothers’ property (presumably in the Marden Hill area, east of Branch Pond); they sold their bricks to neighbors for “chimneys; fireplaces and brick ovens.” A mixture of ashes and clay made mortar, Dowe added.

Another 19th-century brickyard was “in the meadow… where clay was very plentiful” on the Sumner Leeman farm near Greeley Corner, the intersection of what is now Route 3 with Turner Ridge Road, east of the head of Sheepscot Lake.

Sidney had at least one brickyard in 1780. The quotation from Robbins’ Vassalboro history about the importance of brickmaking was in reference to a proposed road on the west side of the Kennebec River (in what became the separate town of Sidney in 1792) that was to follow a way already in use “on the east side of the Brick Kiln at Dudley Does.”

Kingsbury in his Kennebec County history and Alice Hammond in her Sidney history agreed Sidney had many clay deposits. As Kingsbury put it, “wherever bricks were wanted for one or more buildings in times past, when wood for burning them was always at hand, they were made in that locality.” Kingsbury said one yard (perhaps Doe’s) was producing “excellent brick” before 1800.

Hammond mentioned two houses on Middle Road made of brick, reportedly from a nearby brickyard by a brook, and three early River Road farms with brickyards. Perhaps citing Kingsbury, she wrote that in 1860 Nathaniel Chase’s bricks from the Bailey farm (one early Bailey farm was Paul and Betsy’s, on River Road across the Kennebec from Riverside in Vassalboro) “were transported by flat boat to the Augusta market.”

In Vassalboro, Robbins wrote that the Farwell family, Isaac (1704 – 1795) and his son Ebenezer, acquired large tracts in the southern part of town in the 1760s. Their holdings included land around Seven Mile Stream, where they built early mills, and extended south; Isaac built for Ebenezer the large house with white columns called Seven Oaks, still standing on the east (river) side of Riverside Drive (Route 201) near the Augusta line.

Robbins wrote that Isaac’s first house was near a brook – probably Seven Mile Stream – on which he built “a grist mill, saw mill and brick kilns.”

(Another prominent family in southeastern Vassalboro were the Browns, Benjamin and his son Benjamin, Jr. Robbins did considerable research to record their contributions to the town and the area. Riverview, their 1796 one-and-a-half-story Cape house on Riverside Drive, has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 2001.

(Robbins wrote that when Benjamin Brown needed bricks for fireplaces in his “large and quite handsome tavern” that he built sometime before he became postmaster in 1817, he imported them from England. Were the Farwell kilns closed by then? Quite likely; or perhaps the Farwell bricks were not to Brown’s taste.)

And here is another question Robbins raised: did “John DeGrucia, brickmaker,” make bricks in Vassalboro in the 1770s? She wrote that in 1769, DeGrucia “gave bond for forty pounds to Samuel Howard, mariner, for land on the east side of the river on Lot No. 80”; she didn’t mention him again. (Lot 80 is one tier inland from the Kennebec River and about half-way toward Vassalboro’s north boundary.)

In 1806, Robbins found, town meeting voters elected a “Surveyor of Bricks,” apparently for the first time.

When John D. Lang started his first woolen mill, in North Vassalboro, in 1850, Kingsbury wrote that he bought and moved a tannery building. Then he had a brick kiln built on the site, “and after the brick were burned the walls of the mill were built around it.” The mill was added to the National Register of Historic Places on Oct. 5, 2020.

Your writer was unable to find information about Windsor brick production in available sources. Kingsbury made one reference: Thomas Le Ballister, from Bristol, acquired 300 acres in southeastern Windsor and built a log cabin around 1793. When he upgraded to a frame house about 1803, “The chimney was laid with the first bricks manufactured in Windsor.”

In Winslow, Kingsbury listed eight or nine places with “good clay for making brick,” identifying their locations by their pre-1892 owners. A major operation started in 1873 was by 1892 Horace Purinton & Co., with a workforce of 15 and an annual production of 1.5 million bricks.

Kingsbury also described a series of mills built by men named Runnals, Norcross and Hayden on a stream he did not name (identifying it by the mills still operating in 1892). Other sources’ information on the family names suggest it might be Chaffee Brook, which runs into the Kennebec in southern Winslow.

Hayden’s mill dam backed up the stream to make Hayden Mill Pond, and Kingsbury wrote that on one side of the pond was a bed of clay good enough to make pottery. William Hussey, a skilled potter, and Ambrose Bruce started a pottery factory in the late 1820s.

Kingsbury wrote that Hussey’s earthenware was popular – “Most of the milk pans then in use by the housewives in this section were his handiwork.” Unfortunately, according to Kingsbury, Hussey was “[t]oo fond of convivial enjoyments” and drank up so much of the proceeds that the pottery went out of business.

William Hussey is listed in Lura Woodside Watkins’ Early New England Potters and Their Wares, originally published in 1950.

Winslow buildings using brick that Kingsbury mentioned included a century-old house standing in 1892, made of brick from an adjacent yard “near the river two miles above Ticonic falls”; and an early tavern “in a house with a brick front” south of the junction of the Sebasticook River. The Hollingsworth and Whitney mill building, under construction as Kingsbury finished his history, required 2,500,000 bricks, he said.

Winslow’s brick schoolhouse on Cushman Road, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, was described in the Jan. 28, 2021, issue of The Town Line. Two other brick school buildings in Winslow were mentioned in the Oct. 28, 2021 issue.

Update on Fairfield Center’s Victor Grange

Members of Victor Grange #49, in Fairfield Center, organized Oct. 29, 1874, continue to make progress on rehabbing their Grange Hall, which dates from 1903 (see the May 13, 2021, issue of The Town Line). The Grange’s July newsletter reports the building is insulated and as of mid-June has a ventilation system.

The next ambitious project is to have the ground-level hardwood floors professionally refinished, Grange Lecturer Barbara Bailey believes for the first time ever. Grange members need volunteers to help move the furniture from the building to a storage trailer on July 24, beginning about 11 a.m., and will need them again to move everything back about two weeks later. They offer hot dogs and hamburgers to the July 24 crew.

Funds have been donated; Timmy’s Trailers, aka C and J Trailer Repair and Towing, of Fairfield, has loaned the trailer; and Pro Movers, of Waterville, will move out, store and return two pianos.

As a fundraising effort, Grangers are selling more than six dozen 1880s chairs from the organization’s early days, at $10 apiece.

The newsletter writers expressed their appreciation to community members who support the Grange and included the weekly and monthly schedule of ongoing public events. People listed as sources of information about Grange activities are Rita, 453-2945; Roger or Wanda, 453-7193; Marilyn, 453-6937; Deb, 453-4844; Barb, 453-9476; Rick or Lurline, 453-2082; Janice, 453-2266; Steve, 347-254-8556; Anastasia, 835-1930; Tina, 649-5396; and Sherry, 238-0334. The email address is Victorgrange49@gmail.com

Main sources

Dowe, Milton E., History Town of Palermo Incorporated 1884 (1954).

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892),

Lowden, Linwood H., good Land & fine Contrey but Poor roads a history of Windsor, Maine (1993).

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Interesting links

Here are some interesting links for you! Enjoy your stay :)Site Map

- Issue for April 3, 2025

- Issue for March 27, 2025

- Issue for March 20, 2025

- Issue for March 13, 2025

- Issue for March 6, 2025

- Issue for February 27, 2025

- Issue for February 20, 2025

- Issue for February 13, 2025

- Issue for February 6, 2025

- Issue for January 30, 2025

- Issue for January 23, 2025

- Issue for January 16, 2025

- Issue for January 9, 2025

- Issue for January 2, 2025

- Issue for December 19, 2024

- Issue for December 12, 2024

- Issue for December 5, 2024

- Issue for November 28, 2024

- Issue for November 21, 2024

- Issue for November 14, 2024

- Issue for November 7, 2024

- Issue for October 31, 2024

- Issue for October 24, 2024

- Issue for October 17, 2024

- Issue for October 10, 2024

- Issue for October 3, 2024

- Sections

- Our Town’s Services

- Classifieds

- About Us

- Original Columnists

- Community Commentary

- The Best View

- Eric’s Tech Talk

- The Frugal Mainer

- Garden Works

- Give Us Your Best Shot!

- Growing Your Business

- INside the OUTside

- I’m Just Curious

- Maine Memories

- Mary Grow’s community reporting

- Messing About in the Maine Woods

- The Money Minute

- Pages in Time

- Review Potpourri

- Scores & Outdoors

- Small Space Gardening

- Student Writers’ Program

- Solon & Beyond

- Tim’s Tunes

- Veterans Corner

- Donate