1904 Cadillac

Previous articles have discussed transportation by water and overland by railroads, local and long-distance. This article discusses aspects of the evolution of roads and travel over them.

Laying out roads was a major task for local governments in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In the central Kennebec valley area, schools and roads were main topics at town meetings. Local histories quote from town records about deciding where to build roads; when and where to relocate them; when and how to maintain them, at what cost; and when to discontinue them.

Laying out a road, Linwood Lowden explained in his history of Windsor, refers only to choosing the route, not to actually building the road. Some roads laid out were never built. Sometimes male residents were required to contribute labor toward building roads.

As described earlier, the first road in the central Kennebec valley connected the trading post and fort at Cushnoc (now Winslow) with Fort Western (in what is now Augusta). Running along the east bank of the Kennebec, it was completed in 1754. The area around Fort Western and on the west side of the river was all called Hallowell until 1797, when the northern part that is now Augusta was incorporated as Harrington in February and renamed Augusta in June.

Kingsbury wrote in his Kennebec County history that at Hallowell’s first town meeting, held May 22, 1771, at the fort, about 30 voters appropriated 36 British pounds for road-building to connect houses around the fort (and 16 pounds for schools). By 1779, the west side of the river had grown enough so that roads were laid out there. The first part of Augusta’s Water Street came into being in 1784, two rods (33 feet) wide; part of it was widened in 1822, and in 1829 a section was widened again, to 50 feet, Kingsbury wrote.

At Harrington’s first town meeting on April 3, 1797, voters appropriated $1,250 for roads (and only $400 for schools). Kingsbury found that in 1798 Augusta voters laid out a road north to Sidney on the west side of the river and Stone Street going south on the east side. (Stone Street was named to honor Rev. Daniel Stone [1767-1834], a Harvard graduate and Hallowell/Augusta preacher from 1794 to 1809.)

On June 24, 1802, Kingsbury wrote, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts appointed two men, Jonathan Maynard and Lothrop Lewis, to do the ambitious job of laying out a four-rod (66 feet wide) road from Augusta to Bangor, connecting the Kennebec and Penobscot valleys. They were to choose as direct a route as the terrain allowed and to estimate the construction cost. On Feb. 26, 1803, the two were paid $610.04 for their work, included supplies and costs.

Vassalboro voters also began dealing with roads in 1771, according to Robbins’ history, though it is not always clear what they did. For example, Robbins quotes from a Sept. 9, 1771, town meeting report: voters were asked to decide whether to “do their Highway work this year by Rate where they are marked out” and how wide to make roads. The votes were to make the roads “forty rods wide as marked” (40 rods equals 660 feet!) and “Work four days on the highways” (an obligation for each property-owner?).

In March 1772 Vassalboro voters decided to lay out roads according to “Mr. Jones Plan”; but, Robbins added, the Kennebec Proprietors who then owned the area did not hire surveyor John Jones until 1774.

Early roads followed trails or surveyors’ range lines between tiers of lots, or went across private land. Robbins wrote that often voters approved compensation, in early days called an eight-rod allowance (eight rods equals 132 feet), when a road crossed private property instead of following a range line.

Vassalboro voters repeatedly set wage rates for work on roads. In 1804 or 1805, men were paid $1.25 a day. Their oxen earned 43.5 cents daily, and the owners were reimbursed 33.5 cents for a cart and 66.5 cents for a plough. In 1875, men earned 20 cents an hour; a team of oxen got the same rate and a team of horses 25 cents. By 1880 the hourly rates were lower: 15 cents for men and oxen, 10 cents for a single horse and 20 cents for two horses.

In Waterville, Kingsbury wrote that the first streets (he gave no dates) were Front, Main, Water and Silver, running roughly parallel with the river, and Temple, connecting Front and Main. Silver, he said, was named by Isaac Stevens, a wealthy carpenter who lived there along with Nathaniel Gilman and Simeon Mathews and said that among them, they controlled more money than any other three men in town. (Kingsbury does not say whether Gilman Street and Mathews Avenue were named to honor Stevens’ neighbors.)

Elm Street, laid out later, got its name because an early resident, David McFarland, lined it with elm trees. Kingsbury approved.

In Palermo, Millard Howard wrote that the first road, laid out in 1802, connected the southern and northern settlements. The contemporary roughly-corresponding roads, he wrote, are Turner Ridge, Parmenter, Marden Hill and North Palermo.

In 1802, also, the equivalents of Level Hill and Jones Road were laid out. More roads followed in 1805. Then Howard listed some of the complications, like Hostile Valley Road, laid out in 1807, relocated in 1816; or Western Ridge Road, laid out in 1811 and relocated in 1838.

Milton Dowe’s 1996 reminiscence of Palermo ends with a list of 20 discontinued roads, although only 18 are named and several are in China rather than in Palermo. One is described as the first road from George Studley’s house to the Perkins (formerly Black) Cemetery; Dowe added that closing the road explains “why grave markers are now lettered on the back.” (Google map shows the cemetery on the north side of North Palermo Road, just west of the Rowe Road intersection.)

Residents of Freetown (Fairfax after March 1804, now Albion) had held at least two town meetings before a special one on Oct. 8, 1803, at which they appointed three three-man committees to lay out roads in the town’s northern, southern and eastern districts, Ruby Crosby Wiggin wrote. By March 19,1804, when voters accepted all but one of the recommended roads, she deduced that the Bangor and Sebasticook roads were already in use.

Many of the roads went over existing trails, Wiggin wrote. When new roadways separated farms, land was taken equally from owners on both sides.

Model T Ford.

The April 16, 1804, town meeting approved $1,200 for road maintenance, Wiggin found. But the town did not spend any such sum. Instead, each district road commissioner divided his district’s appropriated amount among landowners and offered each the chance to pay his taxes in road work. Most accepted.

In Windsor, Lowden described an 1809 town meeting vote to lay out seven roads. From the descriptions, Lowden was able to identify contemporary equivalents of five. For the other two he was reduced to speculation.

One of the 1809 roads he identified as current Route 17 between South Windsor Corner and Coopers Mills (a village in Whitefield, the town south of Windsor). By 1835, he wrote, this stretch was part of the main road from Augusta to Thomaston. Nonetheless, at a July 18, 1835, town meeting, voters voted to discontinue it. The next month, an attempt to discontinue what is now Windsor’s piece of Route 105 between Augusta and Searsmont failed. (He did not say when Route 17 was reinstituted.)

In the early 20th century, road improvements were a consequence of development of automobiles and trucks. Dowe recalled traveling by Model T Ford (sold from 1908 to 1927, according to the web). A round trip between Palermo and Augusta without a flat tire was a memorable event, he wrote.

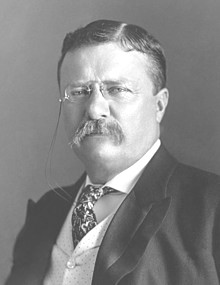

Stanley twins, Francis and Freelan, invented the Stanley Steamer in 1897, in Kingfield, Maine.

In spring, it was smart to travel early in the morning, before roads thawed and turned to mud. When a car got stuck, the driver sought a nearby resident with a horse to rescue him.

In fall, Dowe wrote, ruts were so deep and hard that whenever two cars met on a three-rut road, at least one driver would likely be carrying an axe to cut grooves to let his car move aside.

Dowe wrote that a relative had an eight-passenger Stanley Steamer. To start it, the owner lighted a gasoline burner, which warmed a kerosene burner until it came on and heated water in a boiler to produce steam to run the vehicle. The boiler had a hose so the driver could add water as necessary.

(The Stanley Steamer was invented in 1897 by twin brothers Francis E. and Freelan O. Stanley, born in 1849 in Kingfield, Maine. In 1902 the Stanley Motor Carriage Company was formed in Watertown, Massachusetts. Production declined beginning in 1918 as gasoline-powered cars took over.)

Alice Hammond commented in her history of Sidney that many owners of early cars put them up for the winter and took out their sleighs and sleds. Heavy town-owned snow rollers packed down snow to make a firm surface, instead of shoving it aside.

Horse-drawn snow roller.

Ernest Marriner’s Kennebec Yesterdays includes a not-very-clear 1890s photo of a snow roller with eight horses ready to go, at least three men on board, a bystander with a shovel and two children. The circumference of the roller appears to be approximately the height of the watching man.

In 1907, Hammond wrote, Sidney voters approved a 15-mile-an-hour speed limit for automobiles in town. In 1920, automobiles were included in the list of taxable personal property; there were 55 in town.

There was at least one car in Albion by 1907 (probably more): Wiggin wrote that in that year, Charles Abbott bought a building to garage the first car he owned.

(The building, Wiggin reported, started life as a farmer’s hired man’s house. It was moved and turned into a store that went through at least three owners before Abbott made it his garage. When Abbott became postmaster into 1914, he turned the building into the post office. That incarnation ended in 1960 when Francis Jones built a new post office; the old building was still standing in 1964.)

In China, the bicentennial history tells of a dozen autos early in the 20th century. One was the Oldsmobile runabout Richard Jones, of South China, bought, probably in 1903, for $875. He sent it and Bert Whitehouse to Boston, where Whitehouse learned to drive and maintain the vehicle. They came upriver by boat to Gardiner and Whitehouse drove to Jones’ Pine Rock home on Lakeview Drive.

1920 Velie.

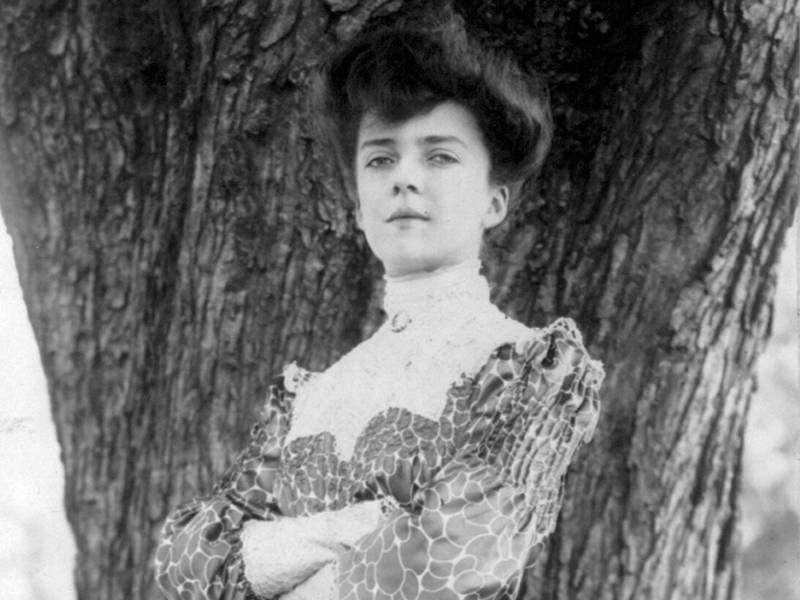

Will Woodsum is credited with bringing the first car to China Village, a 1904 one-cylinder Cadillac he owned by 1909. In 1912, his father, John Woodsum, bought a Velie (one of the early ones; the web says Velies were produced by the Velie Motor Corporation, in Moline, Illinois, between 1908 and 1928).

In 1911, the China history says, Sewall McCartney and Buford Reed bought a second-hand Packard, in Albion; it took them two days to drive it to China, apparently because the engine was seriously underpowered. They sold the engine to Verne Denico, who sawed wood with it, and installed a stationary engine behind the front seats. Years later, someone discovered they had purchased the second Packard ever built.

Main sources

Dowe, Milton E., Palermo, Maine Things That I Remember in 1996, (1997).

Grow, Mary M., China Maine Bicentennial History including 1984 revisions, (1984).

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992, (1992).

Howard, Millard, An Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine (second edition, December 2015).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892), (1892).

Marriner, Ernest, Kennebec Yesterdays, (1954).

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Wiggin, Ruby Crosby, Albion on the Narrow Gauge (1964).

Websites, miscellaneous.

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates

To the editor:

To the editor:

(NAPSI) — Millions of Americans who own an RV have it parked in their driveway or a storage facility for the better part of the year. With many families wary of airplanes and hotels these days, it may be time to consider renting your rig to make some serious cash.

(NAPSI) — Millions of Americans who own an RV have it parked in their driveway or a storage facility for the better part of the year. With many families wary of airplanes and hotels these days, it may be time to consider renting your rig to make some serious cash.

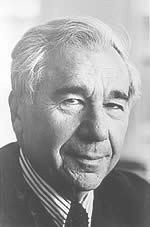

Chris Orestis (www.retirementgenius.com), known as the “Retirement Genius,” is President of LifeCare Xchange and a nationally-recognized healthcare expert and senior advocate. He has 25 years experience in the insurance and long-term care industries, and is credited with pioneering the Long-Term Care Life Settlement over a decade ago. A political insider, Orestis is a former Washington, D.C., lobbyist who has worked in both the White House and for the Senate Majority Leader on Capitol Hill. Orestis is author of the books Help on the Way and A Survival Guide to Aging, and has been speaking for over a decade across the country about senior finance and the secrets to aging with physical and financial health. He is a frequent columnist for Broker World, ThinkAdvisor, IRIS, and NewsMax Finance, has been a featured guest on over 50 radio programs, and has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, CNBC, NBC News, Fox News, USA Today, Kiplinger’s, Investor’s Business Daily, PBS, and numerous other media outlets.

Chris Orestis (www.retirementgenius.com), known as the “Retirement Genius,” is President of LifeCare Xchange and a nationally-recognized healthcare expert and senior advocate. He has 25 years experience in the insurance and long-term care industries, and is credited with pioneering the Long-Term Care Life Settlement over a decade ago. A political insider, Orestis is a former Washington, D.C., lobbyist who has worked in both the White House and for the Senate Majority Leader on Capitol Hill. Orestis is author of the books Help on the Way and A Survival Guide to Aging, and has been speaking for over a decade across the country about senior finance and the secrets to aging with physical and financial health. He is a frequent columnist for Broker World, ThinkAdvisor, IRIS, and NewsMax Finance, has been a featured guest on over 50 radio programs, and has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, CNBC, NBC News, Fox News, USA Today, Kiplinger’s, Investor’s Business Daily, PBS, and numerous other media outlets.

Name the only two players to win a World Series with both the Boston Red Sox and the New York Yankees.

Name the only two players to win a World Series with both the Boston Red Sox and the New York Yankees.