Before moving on to 19th-century Winslow and Waterville high schools, your writer will share one more item about Waterville grammar schools. With its ramifications, it was too long for last week’s article.

Readers learned last week that Waterville school authorities once created two classrooms in the town hall. Following is another example of improvised classroom space, from Henry Kingsbury’s 1892 Kennebec County history.

Kingsbury quoted a resident’s article in the April 21, 1882, “Waterville Mail” remembering when George Dana Boardman taught in “Lemuel Dunbar’s carpenter shop,” because there was no schoolhouse in his newly-created district.

Your writer thought it appropriate to add that Boardman (Feb. 8, 1801 – Feb. 11, 1831) was an internationally known missionary, and Dunbar (May 3, 1781 – c. Aug. 6, 1865) did important work in Waterville.

Boardman, a native of Livermore, Maine, was half the graduating class at the Aug. 1, 1822, first commencement at Waterville College (now Colby College).

He taught at least one term of school in Dunbar’s shop in 1820, while still a student, according to Aaron Appleton Plaisted’s chapter on early settlers in Rev. Edwin Carey Whittemore’s 1902 Waterville history. On July 16 of that year, Kingsbury said, Baptist minister Rev. Jeremiah Chaplin baptized Boardman.

After graduation, according to Wikipedia, Boardman was a Waterville College tutor in 1822-1823, before he went to Andover (Massachusetts) Theological Seminary. When he was ordained a Baptist minister in West Yarmouth, Maine, on Feb. 16, 1825, Wikipedia says Chaplin, by then Waterville College’s President, was a speaker.

On July 4, 1825, Boardman married Sarah Hall (Nov. 4, 1803 – Sept. 1, 1845), from Alstead, New Hampshire. On July 16, they sailed for Calcutta, on their way to Burma (now Myanmar), where they spent their lives as missionaries.

The couple lost at least two sons in infancy; the survivor they named George Dana Boardman (frequently called “the Younger,” Wikipedia says). After Boardman’s early death from consumption (tuberculosis) in Burma, Sarah married another missionary and associate, Adoniram Judson.

* * * * * *

The other half of Boardman’s class was Ephraim Tripp (c. 1799 – April 7, 1871). After graduation, according to on-line information about Waterville/Colby graduates, he served as principal of Hebron Academy in 1822-1823. Then he, too, became a tutor at his alma mater, from 1823 to 1827.

During these years, according to the chapter in Whittemore’s history on Waterville churches, Tripp was one of the three-man building committee for the First Baptist Church, planned in 1824 and dedicated Dec 6, 1826. The dedication ceremony included “a sermon by Dr. Chaplin.”

Later in his life, Tripp was a teacher in Fayetteville, North Carolina, and in Mississippi, and was Clerk of Courts in Carroll County, Mississippi. He died in Winona, Mississippi (now the Montgomery County seat), at the age of 72.

(The author of the chapter on churches in the Waterville history is “George Dana Boardman Pepper, D.D., LL.D., Lately President of Colby College.”

(Pepper [Feb. 5, 1833 – Jan. 30, 1913] was the fourth and last child of John and Eunice [Hutchinson] Pepper. Born in Ware, Massachusetts, he attended two seminaries and Amherst College. From 1860 to 1865, he was pastor of Waterville’s First Baptist Church. Changing to education, he taught religious subjects before and after serving as Colby College’s ninth president from 1882 to 1889. Religion ran in the family; Find a Grave identifies his father as Deacon and one of his older brothers as Rev.)

* * * * * *

Lemuel Dunbar was born in Bridgewater, Massachusetts, and married Cordana Fobes there on June 23, 1806, according to Find a Grave. This source says he bought land in Waterville Oct. 1, 1805; Plaisted said he moved to Waterville around 1808. They agree he built his house and shop at the corner of Main and North streets, at the north end of the present downtown.

Sources disagree on how many children Dunbar had. One implies that Cordana died and he remarried; Find a Grave says Cordana lived until 1869.

Their oldest son was Otis Holmes Dunbar (May 22, 1807 – Sept. 30, 1892), like his father a carpenter. Find a Grave says he was born in Penobscot, Maine; married Mary Talbot in Winslow, Maine, in 1836; worked in Maine and “the Boston area”; and by June 1860 was living in Princeton, Illinois, where he died. His body was returned to Waterville for burial in Pine Grove Cemetery with family members.

Find a Grave says the Dunbars had nine children, born between 1807 and 1826, and lists three daughters and three sons buried in Pine Grove Cemetery. Youngest son Lemuel was the only one still alive in 1902, Plaisted wrote.

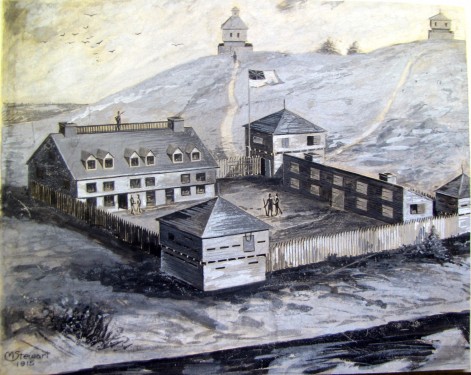

Chaplin taught the first Waterville College classes in July 1818 in a house not far from Dunbar’s shop, according to Edward W. Hall’s chapter on Colby in Whittemore’s history.

Hall continued, “In 1821 the South College was built and eighteen rooms finished besides fitting up a part of the building for a chapel. The second dormitory, known as the North College…was built in 1822.” Dunbar was the carpenter for both buildings, he said.

By 1902, Plaisted said, Dunbar’s original house had been removed and replaced, and the shop had been converted to a house “now occupied by Mr. A. M. Dunbar” (the first Lemuel’s grandson?).

* * * * * *

Your writer’s next topics are Winslow and Waterville high schools, about which she has found little second-hand information. Long-time readers will remember that second-hand information is important: original research, in enclosed spaces among unknown people, has been forbidden since this series started early in the Covid epidemic.

The earliest information your writer found about Winslow high schools was from Kingsbury. He said in 1892, Winslow appropriated $250 to support two free high schools. One, he said, was in “the village of Winslow” and the other “in the eastern part of the town near the Baptist church.” That year they had 80 students between them.

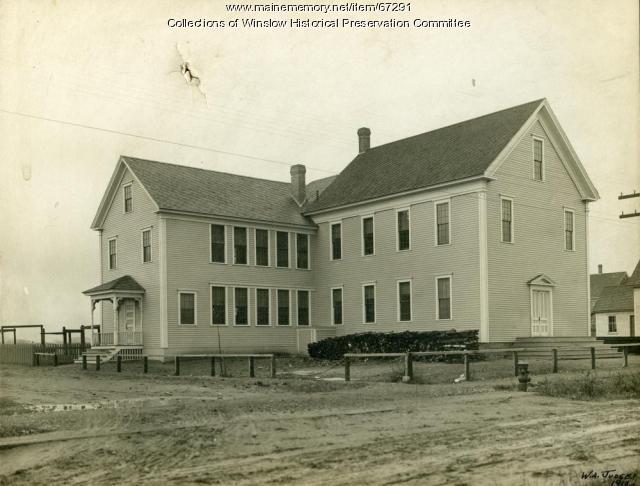

Two on-line sites provide tantalizing bits of information from the first half of the 20th century. One says a wooden, three-story high school building on Halifax Street (which was then Getchell Stret) burned in 1914 and was rebuilt on the same lot in 1915. Halifax Street, also Route 100, runs east from the Kennebec at Fort Halifax.

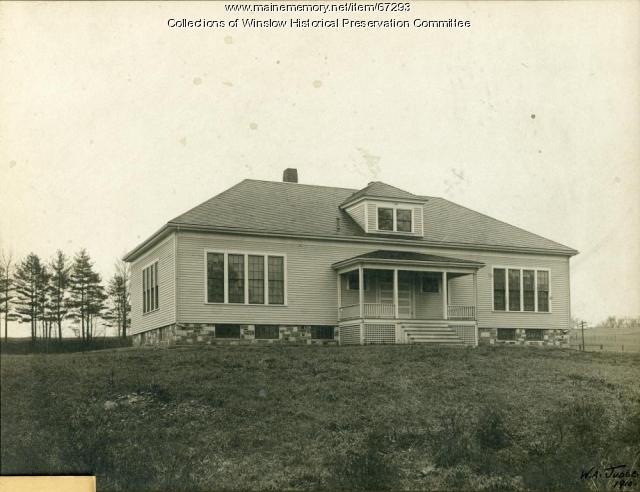

Another site says the new high school that opened on Danielson Street in 1929 replaced the previous schools, plural. The Danielson Street school started out housing grades seven through 12, but seventh grade was soon moved elsewhere. Danielson Street, site of the current Winslow High School, is several blocks north of Halifax Street.

* * * * * *

Your writer’s short part-article on Waterville’s high schools in the Sept. 9, 2021, issue of “The Town Line” is unsatisfactory, in spite of editor Roland Hallee’s attractive illustrations. The following paragraphs will expand it a bit:

Elwood T. Wyman, in his chapter on public schools in Whittemore’s history, listed the “masters” of Waterville’s public high school “since its permanent organization in 1876.” There were nine of them up to 1902, and Richard W. Sprague, Colby Class of 1901, was about to become the tenth. Wyman commented that “every one of the masters in the list quoted has been a Colby graduate.”

This permanently organized school was not Waterville’s first high school, but information on previous ones is scanty. From what Wyman wrote, it appears that by the 1830s, some, at least, of the district schools provided some high-school-level courses. Wyman mentioned that in 1855, “Latin and French were authorized as studies in the high school.”

Education Winslow and Waterville high schools number 224 for Nov 14 2024

Before moving on to 19th-century Winslow and Waterville high schools, your writer will share one more item about Waterville grammar schools. With its ramifications, it was too long for last week’s article.

Readers learned last week that Waterville school authorities once created two classrooms in the town hall. Following is another example of improvised classroom space, from Henry Kingsbury’s 1892 Kennebec County history.

Kingsbury quoted a resident’s article in the April 21, 1882, “Waterville Mail” remembering when George Dana Boardman taught in “Lemuel Dunbar’s carpenter shop,” because there was no schoolhouse in his newly-created district.

Your writer thought it appropriate to add that Boardman (Feb. 8, 1801 – Feb. 11, 1831) was an internationally known missionary, and Dunbar (May 3, 1781 – c. Aug. 6, 1865) did important work in Waterville.

Boardman, a native of Livermore, Maine, was half the graduating class at the Aug. 1, 1822, first commencement at Waterville College (now Colby College).

He taught at least one term of school in Dunbar’s shop in 1820, while still a student, according to Aaron Appleton Plaisted’s chapter on early settlers in Rev. Edwin Carey Whittemore’s 1902 Waterville history. On July 16 of that year, Kingsbury said, Baptist minister Rev. Jeremiah Chaplin baptized Boardman.

After graduation, according to Wikipedia, Boardman was a Waterville College tutor in 1822-1823, before he went to Andover (Massachusetts) Theological Seminary. When he was ordained a Baptist minister in West Yarmouth, Maine, on Feb. 16, 1825, Wikipedia says Chaplin, by then Waterville College’s President, was a speaker.

On July 4, 1825, Boardman married Sarah Hall (Nov. 4, 1803 – Sept. 1, 1845), from Alstead, New Hampshire. On July 16, they sailed for Calcutta, on their way to Burma (now Myanmar), where they spent their lives as missionaries.

The couple lost at least two sons in infancy; the survivor they named George Dana Boardman (frequently called “the Younger,” Wikipedia says). After Boardman’s early death from consumption (tuberculosis) in Burma, Sarah married another missionary and associate, Adoniram Judson.

* * * * * *

The other half of Boardman’s class was Ephraim Tripp (c. 1799 – April 7, 1871). After graduation, according to on-line information about Waterville/Colby graduates, he served as principal of Hebron Academy in 1822-1823. Then he, too, became a tutor at his alma mater, from 1823 to 1827.

During these years, according to the chapter in Whittemore’s history on Waterville churches, Tripp was one of the three-man building committee for the First Baptist Church, planned in 1824 and dedicated Dec 6, 1826. The dedication ceremony included “a sermon by Dr. Chaplin.”

Later in his life, Tripp was a teacher in Fayetteville, North Carolina, and in Mississippi, and was Clerk of Courts in Carroll County, Mississippi. He died in Winona, Mississippi (now the Montgomery County seat), at the age of 72.

(The author of the chapter on churches in the Waterville history is “George Dana Boardman Pepper, D.D., LL.D., Lately President of Colby College.”

(Pepper [Feb. 5, 1833 – Jan. 30, 1913] was the fourth and last child of John and Eunice [Hutchinson] Pepper. Born in Ware, Massachusetts, he attended two seminaries and Amherst College. From 1860 to 1865, he was pastor of Waterville’s First Baptist Church. Changing to education, he taught religious subjects before and after serving as Colby College’s ninth president from 1882 to 1889. Religion ran in the family; Find a Grave identifies his father as Deacon and one of his older brothers as Rev.)

* * * * * *

Lemuel Dunbar was born in Bridgewater, Massachusetts, and married Cordana Fobes there on June 23, 1806, according to Find a Grave. This source says he bought land in Waterville Oct. 1, 1805; Plaisted said he moved to Waterville around 1808. They agree he built his house and shop at the corner of Main and North streets, at the north end of the present downtown.

Sources disagree on how many children Dunbar had. One implies that Cordana died and he remarried; Find a Grave says Cordana lived until 1869.

Their oldest son was Otis Holmes Dunbar (May 22, 1807 – Sept. 30, 1892), like his father a carpenter. Find a Grave says he was born in Penobscot, Maine; married Mary Talbot in Winslow, Maine, in 1836; worked in Maine and “the Boston area”; and by June 1860 was living in Princeton, Illinois, where he died. His body was returned to Waterville for burial in Pine Grove Cemetery with family members.

Find a Grave says the Dunbars had nine children, born between 1807 and 1826, and lists three daughters and three sons buried in Pine Grove Cemetery. Youngest son Lemuel was the only one still alive in 1902, Plaisted wrote.

Chaplin taught the first Waterville College classes in July 1818 in a house not far from Dunbar’s shop, according to Edward W. Hall’s chapter on Colby in Whittemore’s history.

Hall continued, “In 1821 the South College was built and eighteen rooms finished besides fitting up a part of the building for a chapel. The second dormitory, known as the North College…was built in 1822.” Dunbar was the carpenter for both buildings, he said.

By 1902, Plaisted said, Dunbar’s original house had been removed and replaced, and the shop had been converted to a house “now occupied by Mr. A. M. Dunbar” (the first Lemuel’s grandson?).

* * * * * *

Your writer’s next topics are Winslow and Waterville high schools, about which she has found little second-hand information. Long-time readers will remember that second-hand information is important: original research, in enclosed spaces among unknown people, has been forbidden since this series started early in the Covid epidemic.

The earliest information your writer found about Winslow high schools was from Kingsbury. He said in 1892, Winslow appropriated $250 to support two free high schools. One, he said, was in “the village of Winslow” and the other “in the eastern part of the town near the Baptist church.” That year they had 80 students between them.

Two on-line sites provide tantalizing bits of information from the first half of the 20th century. One says a wooden, three-story high school building on Halifax Street (which was then Getchell Stret) burned in 1914 and was rebuilt on the same lot in 1915. Halifax Street, also Route 100, runs east from the Kennebec at Fort Halifax.

Another site says the new high school that opened on Danielson Street in 1929 replaced the previous schools, plural. The Danielson Street school started out housing grades seven through 12, but seventh grade was soon moved elsewhere. Danielson Street, site of the current Winslow High School, is several blocks north of Halifax Street.

* * * * * *

Your writer’s short part-article on Waterville’s high schools in the Sept. 9, 2021, issue of The Town Line is unsatisfactory, in spite of editor Roland Hallee’s attractive illustrations. The following paragraphs will expand it a bit:

Elwood T. Wyman, in his chapter on public schools in Whittemore’s history, listed the “masters” of Waterville’s public high school “since its permanent organization in 1876.” There were nine of them up to 1902, and Richard W. Sprague, Colby Class of 1901, was about to become the tenth. Wyman commented that “every one of the masters in the list quoted has been a Colby graduate.”

This permanently organized school was not Waterville’s first high school, but information on previous ones is scanty. From what Wyman wrote, it appears that by the 1830s, some, at least, of the district schools provided some high-school-level courses. Wyman mentioned that in 1855, “Latin and French were authorized as studies in the high school.”

After 1846, some students qualified for high-school level studies attended one of two private high schools, Waterville Academy (later Coburn Classical Institute) or Waterville Liberal Institute. After the Civil War, Waterville temporarily abandoned its public high school(s).

Wyman wrote: “In 1864 pupils of high school rank were sent to Waterville Academy where Dr. [James] Hanson received $4.50 a term for their tuition. This arrangement was continued until the establishment of an independent high school in 1876.”

(Hanson was then starting his second term as Academy principal; he served from 1843 to 1854 and again from 1865 to his death in 1894.)

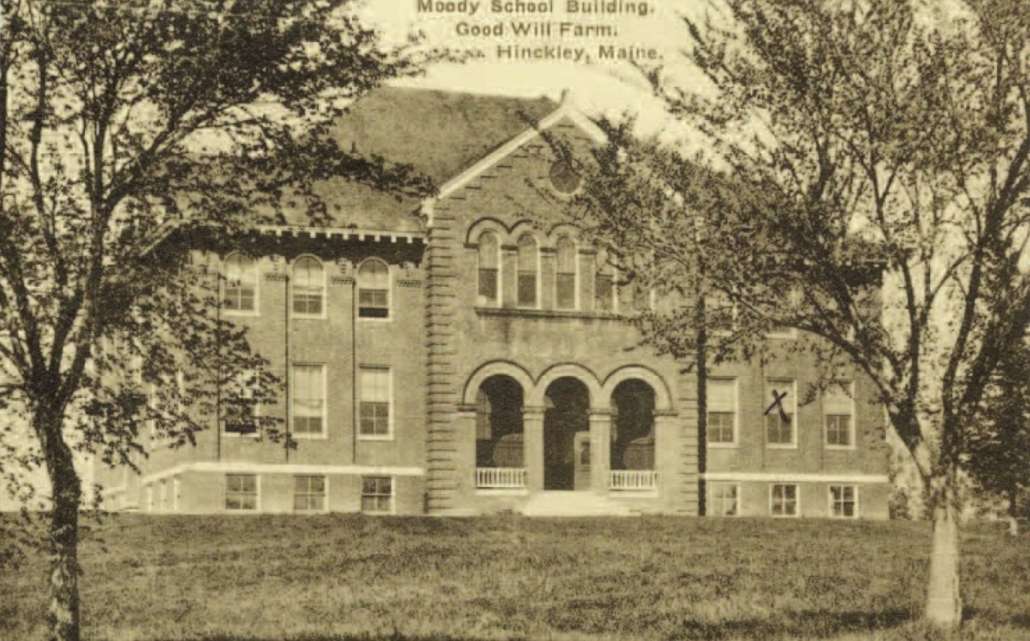

Skipping to 1902, Wyman wrote that the southern of the two brick primary schools built in or soon after 1853 was by then “the main part of the present high school building.” But he did not describe how it attained that role, or where high school classes were held before the mid-1850s or after 1876.

* * * * * *

Waterville Academy was established in 1829 as a preparatory school for Colby College, Waterville Liberal Institute in 1835 as a Universalist high school. (See the Oct. 21, 2021, issue of The Town Line.)

Waterville Academy boys initially took classes at the college. In 1828, college trustees decided on a physically, but not yet legally, separate school.

Timothy Boutelle, a prominent Waterville lawyer, donated land, Wikipedia says, and President Chaplin raised the funds for “a small brick building” where classes started in the fall of 1829, with 61 students. The first head of the academy was Colby senior Henry W. Paine, assisted by a classmate; Kingsbury wrote that Paine returned in August 1831 for another five years.

The Academy closed in 1839 and 1840, because, according to Waterville historian Ernest Marriner, Waterville Liberal Institute took too many of the eligible students. It reopened in 1841 and a year later separated legally from the college.

Kingsbury wrote that in the fall of 1843, when Hanson became principal for the first time, the Academy had five students. By 1853, there were 308 students, and Hanson got an assistant, George B. Gow, who became principal when Hanson left in 1854.

Female students were admitted beginning in 1845. Kingsbury wrote that “another room was fitted up and Miss Roxana F. Hanscom was employed to teach a department for girls.”

In 1865, according to the Wikipedia writer, the Academy was renamed Waterville Classical Institute. In 1882, it was renamed again, Coburn Classical Institute, in honor of benefactor Abner Coburn. In 1970, Coburn merged with Oak Grove School; the combined school closed in 1989.

* * ** * *

Waterville Liberal Institute was chartered by the Maine legislature Feb. 28, 1835, and opened Dec. 12, 1836. The first principal was Nathaniel M. Whitmore, Kingsbury said, and the school started with 54 students.

A “female department” opened in 1850. In 1851, according to that year’s catalog, the Institute had 174 students, 91 boys and 83 girls. Most were from Waterville, but other Maine towns, Massachusetts and New Brunswick were represented.

The Institute closed in 1857, when, Kingsbury wrote, “the growth of Westbrook Seminary sufficiently filled the field.”

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902)

Websites, miscellaneous