In March 15, 1820, Maine became the 23rd state of the United States. Last Sunday was Maine’s 200th anniversary of admission to the union.

HOW MAINE GOT ITS NAME

There is no definitive explanation for the origin of the name “Maine,” but the most likely origin is that the name was given by early explorers after the former province of Maine, in France. Whatever the origin, the name was fixed for English settlers in 1665 when the English King’s Commissioners ordered that the “Province of Maine” be entered from then on in official records. The state legislature in 2001 adopted a resolution establishing Franco-American Day, which stated that the state was named after the former French province of Maine.

Other theories mention earlier places with similar names, or claim it is a nautical reference to the mainland. Captain John Smith, in his “Description of New England” (1614) bemoans the lack of exploration: “Thus you may see, of this 2000 miles more then halfe is yet vnknowne to any purpose: no not so much as the borders of the Sea are yet certainly discovered. As for the goodnes and true substances of the Land, wee are for most part yet altogether ignorant of them, vnlesse it bee those parts about the Bay of Chisapeack and Sagadahock: but onely here and there wee touched or haue seene a little the edges of those large dominions, which doe stretch themselues into the Maine, God doth know how many thousand miles;” Note that his description of the mainland of North America is “the Maine.” The word “main” was a frequent shorthand for the word “mainland” (as in “The Spanish Main”)

Attempts to uncover the history of the name of Maine began with James Sullivan’s 1795 “History of the District of Maine.” He made the unsubstantiated claim that the Province of Maine was a compliment to the queen of Charles I, Henrietta Maria, who once “owned” the Province of Maine in France. This was quoted by Maine historians until the 1845 biography of that queen, by Agnes Strickland, established that she had no connection to the province; further, King Charles I married Henrietta Maria in 1625, three years after the name Maine first appeared on the charter.

The first known record of the name appears in an August 10, 1622, land charter to Sir Ferdinando Gorges and Captain John Mason, English Royal Navy veterans, who were granted a large tract in present-day Maine that Mason and Gorges, “intend to name the Province of Maine.” Mason had served with the Royal Navy in the Orkney Islands, where the chief island is called Mainland, a possible name derivation for these English sailors. In 1623, the English naval captain Christopher Levett, exploring the New England coast, wrote: “The first place I set my foote upon in New England was the Isle of Shoals, being Ilands [sic] in the sea, above two Leagues from the Mayne.” Initially, several tracts along the coast of New England were referred to as Main or Maine (ex.: the Spanish Main). A reconfirmed and enhanced April 3, 1639, charter, from England’s King Charles I, gave Sir Ferdinando Gorges increased powers over his new province and stated that it “shall forever hereafter, be called and named the PROVINCE OR COUNTIE OF MAINE, and not by any other name or names whatsoever …” Maine is the only U.S. state whose name has exactly one syllable.

ORIGINAL INHABITANTS

The original inhabitants of the territory that is now Maine were Algonquian-speaking Wabanaki peoples, including the Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, Penobscot, Androscoggin and Kennebec. During the later King Philip’s War, many of these peoples would merge in one form or another to become the Wabanaki Confederacy, aiding the Wampanoag of Massachusetts and the Mahican, of New York. Afterwards, many of these people were driven from their natural territories, but most of the tribes of Maine continued, unchanged, until the American Revolution. Before this point, however, most of these people were considered separate nations. Many had adapted to living in permanent, Iroquois-inspired settlements, while those along the coast tended to be semi-nomadic – traveling from settlement to settlement on a yearly cycle. They would usually winter inland and head to the coasts by summer.

European contact with what is now called Maine started around 1200 when Norwegians interacted with the native Penobscot in present-day Hancock County, most likely through trade. About 200 years earlier, from the settlements in Iceland and Greenland, Norwegians had first identified America and attempted to settle areas such as Newfoundland, but failed to establish a permanent settlement there. Archaeological evidence suggests that Norwegians in Greenland returned to North America for several centuries after the initial discovery to collect timber and to trade, with the most relevant evidence being the Maine Penny, an 11th-century Norwegian coin found at a Native American dig site in 1954.

The first European settlement in Maine was in 1604 on Saint Croix Island, led by French explorer Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons. His party included Samuel de Champlain, noted as an explorer. The French named the entire area Acadia, including the portion that later became the state of Maine. The first English settlement in Maine was established by the Plymouth Company at the Popham Colony in 1607, the same year as the settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. The Popham colonists returned to Britain after 14 months.

The French established two Jesuit missions: one on Penobscot Bay in 1609, and the other on Mount Desert Island in 1613. The same year, Castine was established by Claude de La Tour. In 1625, Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour erected Fort Pentagouet to protect Castine. The coastal areas of eastern Maine first became the Province of Maine in a 1622 land patent. The part of western Maine north of the Kennebec River was more sparsely settled, and was known in the 17th century as the Territory of Sagadahock. A second settlement was attempted in 1623 by English explorer and naval Captain Christopher Levett at a place called York, where he had been granted 6,000 acres by King Charles I of England. It also failed.

Central Maine was formerly inhabited by people of the Androscoggin tribe of the Abenaki nation, also known as Arosaguntacook. They were driven out of the area in 1690 during King William’s War. They were relocated at St. Francis, Canada, which was destroyed by Rogers’ Rangers in 1759, and is now Odanak. The other Abenaki tribes suffered several severe defeats, particularly during Dummer’s War, with the capture of Norridgewock in 1724 and the defeat of the Pequawket in 1725, which greatly reduced their numbers. They finally withdrew to Canada, where they were settled at Bécancour and Sillery, and later at St. Francis, along with other refugee tribes from the south.

HOW MAINE BECAME PART OF MASSACHUSETTS

Maine in 1798.

The province within its current boundaries became part of Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1652. Maine was much fought over by the French, English, and allied natives during the 17th and early 18th centuries, who conducted raids against each other, taking captives for ransom or, in some cases, adoption by Native American tribes. A notable example was the early 1692 Abenaki raid on York, where about 100 English settlers were killed and another estimated 80 taken hostage. The Abenaki took captives taken during raids of Massachusetts in Queen Anne’s War of the early 1700s to Kahnewake, a Catholic Mohawk village near Montreal, where some were adopted and others ransomed.

After the British defeated the French in Acadia in the 1740s, the territory from the Penobscot River east fell under the nominal authority of the Province of Nova Scotia, and together with present-day New Brunswick formed the Nova Scotia county of Sunbury, with its court of general sessions at Campobello. American and British forces contended for Maine’s territory during the American Revolution and the War of 1812, with the British occupying eastern Maine in both conflicts. The territory of Maine was confirmed as part of Massachusetts when the United States was formed following the Treaty of Paris ending the revolution, although the final border with British North America was not established until the Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1842.

Maine was physically separate from the rest of Massachusetts. Long-standing disagreements over land speculation and settlements led to Maine residents and their allies in Massachusetts proper forcing an 1807 vote in the Massachusetts Assembly on permitting Maine to secede; the vote failed. Secessionist sentiment in Maine was stoked during the War of 1812 when Massachusetts pro-British merchants opposed the war and refused to defend Maine from British invaders. In 1819, Massachusetts agreed to permit secession, sanctioned by voters of the rapidly growing region the following year. Formal secession and formation of the state of Maine as the 23rd state occurred on March 15, 1820, as part of the Missouri Compromise, which geographically limited the spread of slavery and enabled the admission to statehood of Missouri the following year, keeping a balance between slave and free states.

Maine’s original state capital was Portland, Maine’s largest city, until it was moved to the more central Augusta in 1832. The principal office of the Maine Supreme Judicial Court remains in Portland.

The 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment, under the command of Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, prevented the Union Army from being flanked at Little Round Top by the Confederate Army during the Battle of Gettysburg.

Four U.S. Navy ships have been named USS Maine, most famously the armored cruiser USS Maine (ACR-1), whose sinking by an explosion on February 15, 1898, precipitated the Spanish–American War.

THE FINAL PUSH TO STATEHOOD

The Missouri Compromise was United States federal legislation that admitted Maine to the United States as a free state, simultaneously with Missouri as a slave state – thus maintaining the balance of power between North and South in the United States Senate. As part of the compromise, the legislation prohibited slavery north of the 36°30′ parallel, excluding Missouri. The 16th United States Congress passed the legislation on March 3, 1820, and President James Monroe signed it on March 6, 1820.

Earlier, in February 1819, Representative James Tallmadge Jr., a Jeffersonian Republican from New York, submitted two amendments to Missouri’s request for statehood, which included restrictions on slavery. Southerners objected to any bill that imposed federal restrictions on slavery, believing that slavery was a state issue settled by the Constitution. However, with the Senate evenly split at the opening of the debates, both sections possessing 11 states, the admission of Missouri as a slave state would give the South an advantage. Northern critics including Federalists and Democratic-Republicans objected to the expansion of slavery into the Louisiana Purchase territory on the Constitutional inequalities of the three-fifths rule, which conferred Southern representation in the federal government derived from a states’ slave population. Jeffersonian Republicans in the North ardently maintained that a strict interpretation of the Constitution required that Congress act to limit the spread of slavery on egalitarian grounds. “[Northern] Republicans rooted their antislavery arguments, not on expediency, but in egalitarian morality”; and “The Constitution [said northern Jeffersonians], strictly interpreted, gave the sons of the founding generation the legal tools to hasten the removal of slavery, including the refusal to admit additional slave states.”.

When free-soil Maine offered its petition for statehood, the Senate quickly linked the Maine and Missouri bills, making Maine admission a condition for Missouri entering the Union as a slave state. Senator Jesse B. Thomas, of Illinois, added a compromise proviso that excluded slavery from all remaining lands of the Louisiana Purchase north of the 36° 30′ parallel. The combined measures passed the Senate, only to be voted down in the House by those Northern representatives who held out for a free Missouri. Speaker of the House Henry Clay, of Kentucky, in a desperate bid to break the deadlock, divided the Senate bills. Clay and his pro-compromise allies succeeded in pressuring half the anti-restrictionist House Southerners to submit to the passage of the Thomas proviso, while maneuvering a number of restrictionist House northerners to acquiesce in supporting Missouri as a slave state. The Missouri question in the 15th Congress ended in stalemate on March 4, 1819, the House sustaining its northern antislavery position, and the Senate blocking a slavery restricted statehood.

When free-soil Maine offered its petition for statehood, the Senate quickly linked the Maine and Missouri bills, making Maine admission a condition for Missouri entering the Union as a slave state. Senator Jesse B. Thomas, of Illinois, added a compromise proviso that excluded slavery from all remaining lands of the Louisiana Purchase north of the 36° 30′ parallel. The combined measures passed the Senate, only to be voted down in the House by those Northern representatives who held out for a free Missouri. Speaker of the House Henry Clay, of Kentucky, in a desperate bid to break the deadlock, divided the Senate bills. Clay and his pro-compromise allies succeeded in pressuring half the anti-restrictionist House Southerners to submit to the passage of the Thomas proviso, while maneuvering a number of restrictionist House northerners to acquiesce in supporting Missouri as a slave state. The Missouri question in the 15th Congress ended in stalemate on March 4, 1819, the House sustaining its northern antislavery position, and the Senate blocking a slavery restricted statehood.

The Missouri Compromise was controversial at the time, as many worried that the country had become lawfully divided along sectional lines. The Kansas–Nebraska Act effectively repealed the bill in 1854, and the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857). This increased tensions over slavery and eventually led to the Civil War.

The District of Maine was the governmental designation for what is now the U.S. state of Maine from October 25, 1780, to March 15, 1820, when it was admitted to the Union as the 23rd state. The district was a part of the state of Massachusetts (which prior to the American Revolution was the British province of Massachusetts Bay).

Originally settled in 1607 by the Plymouth Company, the coastal area between the Merrimack and Kennebec rivers, as well as an irregular parcel of land between the headwaters of the two rivers, became the province of Maine in a 1622 land grant. In 1629, the land was split, creating an area between the Piscataqua and Merrimack rivers which became the province of New Hampshire. It existed through a series of land patents made by the kings of England during this era, and included New Somersetshire, Lygonia, and Falmouth. The province was incorporated into the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the 1650s, beginning with the formation of York County, Massachusetts, which extend from the Piscataqua River to just east of the mouth of the Presumpscot River in Casco Bay. Eventually, its territory grew to encompass nearly all of present-day Maine. The large size of the county led to its division in 1760 through the creation of Cumberland and Lincoln counties.

The northeastern portion of present-day Maine was first sparsely occupied by Maliseet Indians and French settlers from Acadia. The lands between the Kennebec and Saint Croix rivers were granted to the Duke of York in 1664, who had them administered as Cornwall County, part of his proprietary Province of New York. In 1688, these lands (along with the rest of New York) were subsumed into the Dominion of New England. English and French claims in western Maine would be contested, at times violently, until the British conquest of New France in the French and Indian War. With the creation of the Province of Massachusetts Bay in 1692, the entirety of what is now Maine became part of that province.

When Massachusetts adopted its state constitution in 1780, it created the District of Maine to manage its northernmost counties, bounded on the west by the Piscataqua River and on the east by the Saint Croix River. By 1820, the district had been further subdivided with the creation of Hancock, Kennebec, Oxford, Penobscot, Somerset, and Washington counties.

A movement for Maine statehood began as early as 1785, and in the following years, several conventions were held to effect this. Starting in 1792 five popular votes were taken but all failed to reach the necessary majorities. During the War of 1812, British and Canadian forces occupied a large portion of Maine including everything from the Penobscot River east to the New Brunswick border. A weak response by Massachusetts to this occupation contributed to increased calls in the district for statehood.

The Massachusetts General Court passed enabling legislation on June 19, 1819, separating the District of Maine from the rest of the Commonwealth. The following month, on July 19, voters in the district approved statehood by 17,091 to 7,132.

In Kennebec County, the vote was 3,950 in favor, 641 opposed; In Somerset County the results were 1,440 in favor, 237 opposed.

Thus, Maine became the 23rd state admitted to the U.S. on March 15, 1820.

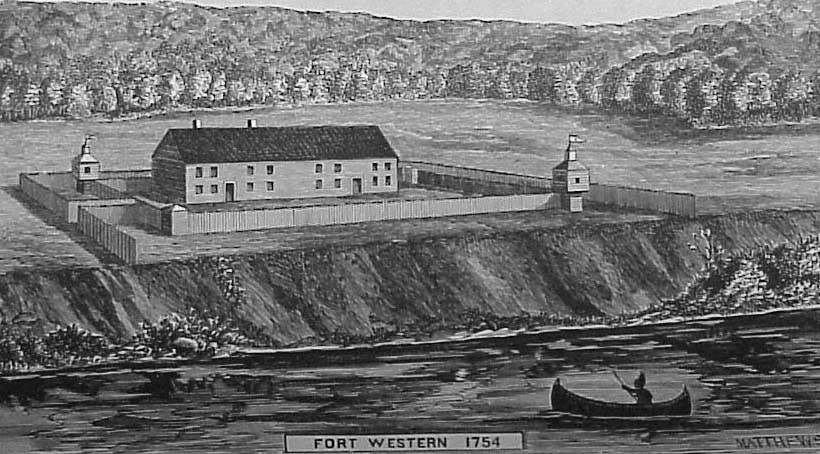

From the coast, European exploration, land claims and settlements moved inland up rivers, for the obvious reason that boats and ships were the major means of moving people and especially goods. Although the area was well inhabited before Europeans arrived, Native tribes did not use wheeled vehicles; their trails were unsuited to wagons and even to horseback riders.

From the coast, European exploration, land claims and settlements moved inland up rivers, for the obvious reason that boats and ships were the major means of moving people and especially goods. Although the area was well inhabited before Europeans arrived, Native tribes did not use wheeled vehicles; their trails were unsuited to wagons and even to horseback riders.

State celebrates 200th anniversary on March 15

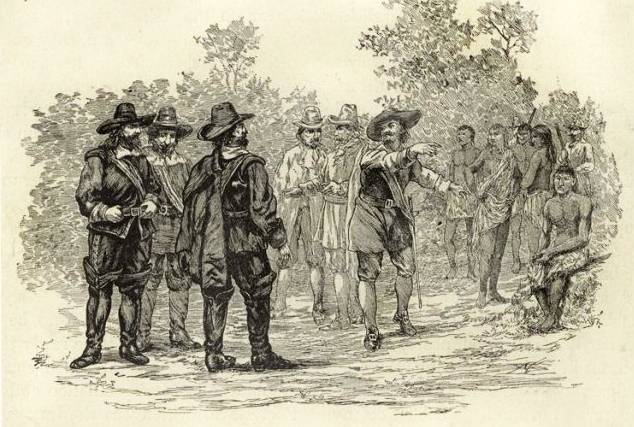

State celebrates 200th anniversary on March 15 Hopelessly caught between the colonial aims of several European nations, primarily England and France, Maine’s native population never stood a chance. Dozens of tribes in western Maine were decimated by an endless series of war, disease, trauma, and displacement from their homelands. Their cultural presence has been lost to the world; their histories are told by white men. This presentation locates the tribes along western Maine rivers and identifies the forces that sealed their fates. Learn of the names of Wawenocks kidnapped by George Weymouth and Capt. Henry Harlow, of the murder of Squanto, and of the western Maine Indians who were tricked into capture at Dover, New Hampshire, and later imprisoned, hanged, or sold into slavery never to be heard from again.

Hopelessly caught between the colonial aims of several European nations, primarily England and France, Maine’s native population never stood a chance. Dozens of tribes in western Maine were decimated by an endless series of war, disease, trauma, and displacement from their homelands. Their cultural presence has been lost to the world; their histories are told by white men. This presentation locates the tribes along western Maine rivers and identifies the forces that sealed their fates. Learn of the names of Wawenocks kidnapped by George Weymouth and Capt. Henry Harlow, of the murder of Squanto, and of the western Maine Indians who were tricked into capture at Dover, New Hampshire, and later imprisoned, hanged, or sold into slavery never to be heard from again.

The Kennebec Historical Society is seeking submissions for a logo design for use primarily across digital media.

The Kennebec Historical Society is seeking submissions for a logo design for use primarily across digital media.