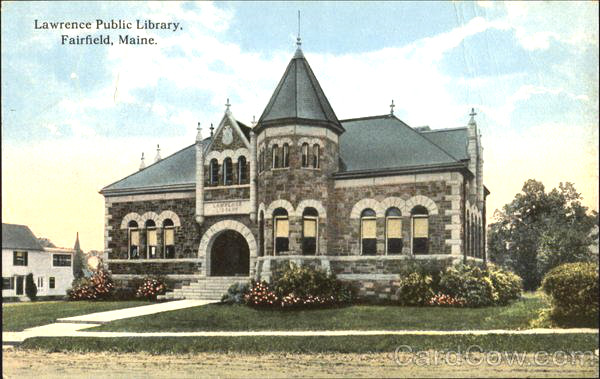

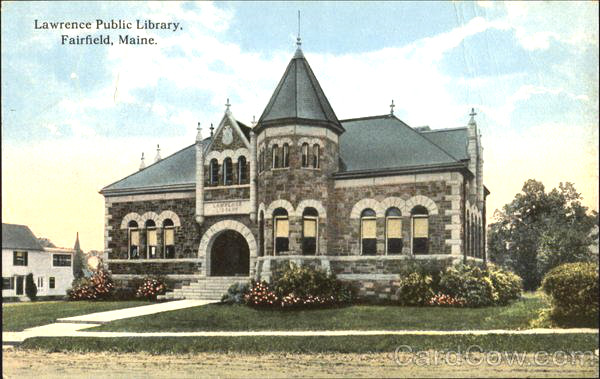

The Lawrence Library, in Fairfield.

The differential treatment in education discussed last week did not necessarily make women less interested than men in learning and literature. Local histories mention discussion and debate groups, most by and for men, some by and for women, and early libraries.

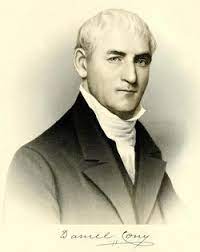

Daniel Cony

Augusta had two men’s literary groups, one formed in 1817 and a successor in 1829. Kingsbury credits Daniel Cony’s example for “a reading room and social library organization” started on Oct. 1, 1817.

It was reorganized June 2, 1819, and chartered June 20, 1820, as the Augusta Union Society. The Society’s incorporation was “the first act passed by the legislature of Maine” after the separation from Massachusetts, according to James North’s Augusta history.

North wrote that the Union Society’s goal was “improvement in useful knowledge by means of a library of choicely selected books, magazines and public newspapers.” By 1825, the Society had outgrown its first headquarters and moved to the Kennebec Journal building on Winthrop Street. The Union Society had disbanded by October 1829, Kingsbury said.

In the 1820s, North said, Cony’s Female Academy had the largest library in Augusta. There was also William Dewey’s circulating library.

By then, North wrote, debating societies were common. He mentioned the Nucleus, organized in 1825, and the Franklin Debating Club.

Both Kingsbury and North offered information on the Augusta Lyceum, which Kingsbury said replaced the Union Society in 1829, “as the organized exponent of the intelligence of the town.” North explained that lyceums succeeded debating societies as “a form better calculated to impart instruction, and at the same time afford equal amusement.”

North said the Augusta Lyceum’s October 1829 constitution established dues at 50 cents a quarter-year (25 cents for members under 18), and life memberships were $20. Meetings were weekly, with monthly debates that Kingsbury said “were sometimes brilliant and exciting.”

North offered as an example the debate over the treatment of Indians by Puritans. Discussion continued for weeks, with clergymen on one side and “a vigorous attacking party” on the other. The eventual decision was “against the Puritans, more from a spirit of victory in debate than any intention to defame that noble but austere race of men.”

Another interesting evening North described was April 18, 1830, when John A. Vaughn, of Hallowell, delivered an illustrated talk on railroads, which were not to reach Augusta until 1851.

Vaughn brought a model railroad, with two cars attached to each other. One held two 56-pound weights, the other a grey squirrel running on a treadmill. The squirrel’s motion pulled the heavier car, illustrating the minimal energy needed for a great effect.

Vaughn also had a picture and explanation of a British “Novelty Steam Carriage,” which provided 30-mile-an-hour passenger service. He concluded by predicting the expansion of railways throughout the United States, North said with impressive accuracy.

The Lyceum movement was national, at the state, county and town level, North wrote. The institutions became “a prominent educational means by developing a spirit of inquiry and creating a fondness for reading and a pleasure in receiving and imparting knowledge heretofore unexperienced by the mass of the community.”

State and county lyceums did not last long; local ones continued into the 1850s. North blamed their decline and disappearance on “a plethoric feeling which constantly demanded, from year to year, a higher grade of talent in lectures and new sources of excitement.”

In the adjoining town of Vassalboro, Alma Pierce Robbins’ history mentions, but provides too few details about, groups whose members might have been interested in reading, as well as sociability and needlework. Three appear to have been women’s organizations.

Local organizations on Webber Pond Road included a Christmas Club, apparently primarily a women’s needlework group, and a Browning Club, a Vassalboro branch of the international group organized in 1895 to expand women’s literary and cultural knowledge and named for English poets Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

(At a 2017 meeting reported on line, a Browning Club historian said the organization “served as an outlet for its members to educate each other during a time when attitudes toward women did not include higher education.”

She continued, “[T]hese women strived to provide each other with the opportunity to read, explore, and learn from one another.”)

Robbins said Vassalboro’s Christmas and Browning clubs met year-round at members’ houses. She did not date either organization.

In Riverside, she continued, there was a Riverside Corporation and later a Community Club, about which she provided no information beyond the names; and a “Riverside Study Club.” Vassalboro Historical Society President Janice Clowes says the Study Club was organized in 1947 and disbanded in 2001; Robbins wrote that it “became an affiliate of the State Federation of Women’s Clubs in 1949.”

Waterville, according to Whittemore’s history, was home to a series of debating clubs, exclusively for men. The earliest he mentioned was the Ticonick Debating Society, started Sept. 18, 1824, with “the leading men in the town” as founding members.

It was succeeded in 1837 by the Waterville Lyceum, which Whittemore said lasted only two years. Its 1841 successor, the Waterville Debating Society, apparently lasted a year. The Mechanics’ Debating Club Whittemore dates in the mid-1850s.

The Woman’s Association in Waterville was organized in 1887 and was still going strong, with 50 members, when Kingsbury published his history in 1892. He said its purpose was to provide women and girls with “useful information” and “special instruction.”

The organization had a 400-volume library. It sponsored evening classes “through the cold seasons,” where attendees could learn “needlework, penmanship, music and a variety of useful arts.”

Contemporary Facebook pages on the web list a Waterville Woman’s Association, founded in 1887, and a Waterville Area Women’s Club, founded in 1893.

The only similar organization Linwood Lowden mentioned in his history of Windsor was not organized until 1913, and was primarily a social group. The Unity Club, organized Dec. 17, 1913, apparently lasted into the 1930s, Lowden wrote.

Lowden said the “short literary program” that was initially part of each twice-a-month meeting was frequently replaced by a social service type activity, like making baby clothes for a needy family or knitting for the Red Cross.

* * * * * *

It is tempting to consider literary groups as precursors to public libraries, and one women’s group clearly was.

According to the Fairfield bicentennial history and an on-line source, a group of 24 women, led by Addie M. Lawrence, Mary Newhall and Frances Kenrick, organized a circulating library called the Ladies Book Club in 1895 or 1896. The club started with 48 books, kept in two bookcases in a small room above C. E. Holt’s candy store on Main Street.

The bookcases could accommodate 200 books, the history says, and were filled in three years. In July 1899, the club moved to two rooms in a Fairfield bank (the history is inconsistent in naming the bank), where residents continued to donate books and magazines.

Addie Lawrence was Edward Jones Lawrence’s daughter, and she “persuaded her father to offer the town a public library.” (Edward Jones Lawrence also established Fairfield’s Lawrence High School; see The Town Line, Oct. 7, 2021.)

At the March 1900 town meeting, voters accepted the offer. In May 1900, the renamed Fairfield Book Club held a meeting at which Lawrence promised to build a library when a site was found. Louise E. Newhall donated a lot between her house and Lawrence’s house, on the south side of Lawrence Avenue, facing the town park.

The result was Lawrence Library, which has been on the National Register of Historic Places since Dec. 31, 1974.

It had one precursor, according to the Fairfield history. The writers quote from the Jan. 29, 1867, issue of the Fairfield Woodpecker the statement that “The Ladies Library had been very active prior to the Civil War but was not used much at this time.”

(The Woodpecker was published in Kendall’s Mills, the name for what is now downtown Fairfield, from 1867 to at least 1874. The Fairfield Historical Society has copies on film; the Lawrence Library also has copies, according to an on-line site.)

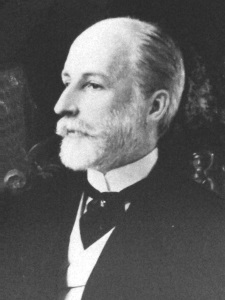

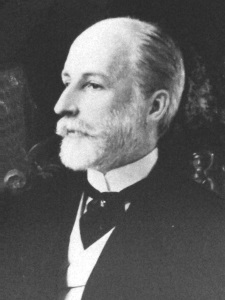

William R. Miller

Maine architect William R. Miller designed the new library. In the application for National Register listing, Earle Shettleworth, of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission, described the architecture as Romanesque Revival modified by H. H. Richardson.

Miller (1866-1929) was born in Durham, Maine, and worked mostly in Maine throughout his career, based first in Lewiston and later in Portland. Wikipedia says his projects included “schools, libraries, hotels and churches as well as private residences.”

Other local buildings Miller designed include the original Lawrence High School, the Gerald Hotel and two Goodwill-Hinckley buildings in Fairfield, and Waterville’s Carnegie Library.

Henry H. Richardson

Henry Hobson Richardson (1838-1886) developed the form called Richardson Romanesque. Wikipedia says he is considered one of the titans of American architecture, with Louis Henry Sullivan (1856-1924) and Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959).

The Lawrence Library building is made of “slate rock with granite trim,” Shettleworth wrote. It is two stories high with a hip roof. The rock is of different colors, mostly variations on light reddish-brown, with darker browns and greys interspersed.

The main entrance door on the north side, facing the park, is set under a large granite arch. Above the arch, a sign identifies the building. An elaborate edifice above the sign includes three stained-glass windows inside granite-topped arches flanked by small towers. Still higher is a shield labeled “1900” (the year construction started) below a peaked roof.

Beside the entrance is an octagonal tower with more arched windows. On either side of the door and tower, the main floor rooms have large triple-arched windows. Granite above the windows and on the building’s corners and “cornice level granite strong courses” contrast with the vari-colored stone.

Shettleworth wrote that the same themes – stone, granite and arched windows – were continued around the building, with the back (south) side the least elaborate.

Lawrence Library was dedicated July 25, 1901. Shettleworth quoted physical descriptions, but nothing about the ceremony, from the July 26, 1901, issue of the Waterville Sentinel.

The newspaper writer said the stacks in the west room could hold 5,000 books and were almost full. The books were “arranged according to the Dewey system and a glance over the titles will delight the soul of any book lover,” he wrote.

The east room was the reading room. The “pastel portrait” of Edward Lawrence was done by Flora Gross Clark; the Fairfield Book Club donated it. Also mentioned were the oil painting of the Moor of Venice by local artist F. E. McFadden (who was also a lawyer and in the 1880s town clerk for at least two years); and the “splendid globe,” “18 inches in diameter… on a bronze pedestal 43 inches high” given by Mrs. E. P. Kenrick.

The Clark and McFadden portraits still hang in the east room. Portraits of Addie and Alice Jones, set in stained glass rectangles, decorate the wall behind the librarian’s desk. Overhead, the inside rim of an off-white dome lists well-known New England writers.

Above the front door, a large bronze plaque says Jones donated the building and 2,000 books, and Newhall donated the land and another 2,000 books. Librarian Louella Bickford says the plaque is identified on the back as made by Tiffany, the New York studio led by Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933).

Commenting on Edward Jones Lawrence, the 1901 Sentinel writer observed that many towns owed their libraries to “the Scotland born and American made millionaire” [Andrew Carnegie], others to a native son who made his fortune elsewhere.

But, he wrote, “Fairfield rejoices in the gift of a man who was born within her borders, educated in her public schools and whose position of wealth and influence among the foremost business men in the State has been won in his native town. … He is one also who has worked his way up from the bottom of the ladder by his hard work and who has shown that success is possible for any man in Maine and in Fairfield. The gift is therefore especially prized.”

* * * * * *

Six-masted schooner Addie M. Lawrence was launched on December 17, 1902. It carried military supplies in World War I and ran aground in a gale off the coast of Brittany on July 9, 1917.

Three of the schooners that Lawrence helped finance in Bath were named the Addie M. Lawrence, the Alice M. Lawrence and the Edward J. Lawrence.

The Dec. 23, 1902, Fairfield Journal reported that the “Addie M.” was launched at 12:45 p.m. on Dec. 17, “a date that will long be remembered by many as one of great pleasure.”

The six-masted schooner was built at Percy & Small’s shipyard at a cost of $130,000. The reporter wrote that she was 2923 feet long and 483 feet wide, a patent absurdity; another on-line source gives the dimensions as 292 feet, four inches by 48 feet, three inches. Each mast was 118 feet tall; topmasts were 56 feet long, and the sails totaled “about 8700 yards of canvas.”

Wikipedia says the largest sailing ship ever built was another Percy & Small six-masted schooner, the Wyoming. Launched in 1909, she had an overall length of 450 feet, counting her 86-foot jib boom and “protruding spanker boom”; her deck length was 334 feet. (The jib boom is an extension of the bowsprit; the spanker boom supports a sail over the stern.)

(For more comparisons, the RMS Titanic was 882 feet, nine inches long. The future USS Daniel Inouye, the U. S. Navy’s newest guided missile destroyer, launched from Bath Iron Works Oct. 4, 2021, is 513 feet long. The Daniel Inouye is scheduled to be commissioned at her home port, Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in December.)

The 1902 Journal reporter said the “Addie M.” had three cabins, the aft (stern) one “a thing of beauty being of quartered oak, mahogany and cypress with furniture of leather trimmings.” Sternward rooms were gold and black, forward rooms aluminum and black; the captain had an office “and a stateroom prettily furnished and very light and pleasant.”

For the launching, the ship was decorated with flags and bunting. Addie Lawrence smashed the traditional bottle of champagne against the bow as the ship started down the ways.

The reporter was one of a “large crowd,” including many Fairfield residents. He wrote, “[W]hen the giant craft had left her cradle and made a mighty leap into the river a mighty cheer went up from the bystanders, while all the neighboring craft and manufacturing establishments along the river saluted by blowing three long whistles, to which the Lawrence responded.”

The South Portland Historical Society has a history of the Addie M. Lawrence that says she carried military supplies in World War I and ended her career off the coast of Brittany on July 9, 1917, when she ran aground in a gale.

Another on-line site says six-masted schooners were too big to be practical. Fewer than a dozen were built; the Edward J. Lawrence, built in 1908 and burned in 1925, was the last in use.

Edward Jones Lawrence

Edward Jones Lawrence (Jan. 1, 1833 – Nov. 27, 1918) was educated through sixth grade and first worked as a farm hand in Fairfield Center, his birthplace. A job in a Norridgewock store gave him bookkeeping experience, which led to an accounting position with the Gardiner-based lumber business Wing and Bates.

In 1860 he bought a one-third ownership in Wing and Bates. After another decade, he and his brother, George W. Lawrence, had money enough to buy the company’s Shawmut building and replace it with their own mill.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, the Fairfield history says, Lawrence and Benton native Amos Gerald “invested extensively in street railroads.” An on-line source lists him as president of two street railway companies, the Waterville and Oakland and the Portland and Brunswick, in 1909.

The Lombard log hauler, which used to be on exhibit near the Waterville-Winslow Bridge, is now on display at the Redington Museum, on Silver St., in Waterville.

Other ventures included supporting Alvin Lombard’s Lombard hauler; supporting Martin Keyes’ pulp-wood plate business, ancestor of today’s Keyes Fibre* (“Keyes’ first machinery was set up at the Lawrence mill” in Shawmut); and investing in ship-building in Bath.

After Lawrence’s first wife died in 1865, in 1868 (or 1870; sources differ) he married Hannah Miller Shaw, who became the mother of Annie (born in 1870, died in 1886), Addie (born in 1873) and Alice (born in 1879).

The bicentennial history says Lawrence moved from Shawmut to Fairfield, where he built “the grand house at the corner of High Street and Lawrence Avenue,” because he wanted his daughters educated and Fairfield had better schools. He represented Fairfield in the state legislature for one term, in 1877, as a member of the Greenback Party.

A history of Lawrence Library says Representative Jones fought for two causes, safe working conditions and fair pay for workers and legislation “allowing only the federal government to print paper money.”

After Annie’s death in 1886, Hannah had a nervous breakdown, and the two younger girls went to a Massachusetts boarding school.

Both were artistically talented. Addie was on the verge of becoming a portrait painter, but returned to Fairfield because of her mother’s health and family finances. Alice studied piano with pianist and composer John Carver Alden (1852-1935). She married Walter Daub and had two daughters; and after a divorce in 1919 returned to Fairfield.

Alice’s older daughter, Mary Lawrence (Daub) Halkyard (Sept. 25, 1910 – Nov. 15, 2013), and her husband Neil were teachers; they founded the Shepherd Knapp School, in Boylston, Massachusetts. The school no longer exists, but its building, which dates from 1848, is a National Historic Landmark.

After retiring from teaching, the Halkyards lived in China (Maine) when they were not traveling. Mary Halkyard remained fond of, and like her grandfather generous to, the Town of Fairfield.

* Today’s Huhtamaki plant.

Main sources

Fairfield Historical Society, Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed. , Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Lowden, Linwood H., good Land & fine Contrey but Poor roads a history of Windsor, Maine (1993).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous.

One of the primary goals of Scouting is to instill in young people a desire to become participating citizens and foster good citizenship. During Veterans Day, Scouts all over the area were busy working alongside veterans in several projects and events.

One of the primary goals of Scouting is to instill in young people a desire to become participating citizens and foster good citizenship. During Veterans Day, Scouts all over the area were busy working alongside veterans in several projects and events.