Victor Grange,

Victor and Hinckley

The members of the next Grange to be discussed should be proud to belong to one of the earliest Grange organizations in the central Kennebec Valley area, and one that is still active in its 147th year.

Victor Grange #49 was organized on October 29, 1874, when, the Fairfield bicentennial history says, “a group of men and women met at the home of Mr. James Porter at the top of what is known as ‘Fuller Hill’ in Fairfield Center.” The Grange was incorporated in 1888.

The new Grange started with 29 charter members, 11 of them women. As with the Albion Grange profiled in the April 8 issue of “The Town Line”, at first only farmers could join. By the 1988 publication of the Fairfield history, membership was open to “those interested in farming and in the welfare of others.”

Barbara Bailey, of Larone (northernmost of Fairfield’s seven villages), is Victor Grange’s lecturer. (Maine State Grange Communications Director Walter Boomsma says the title “lecturer” now means program director.) Bailey has been reading Victor Grange’s records (as of early May, she reported she was up to 1914).

The bicentennial history identifies the first Victor Grange Master as Olando A. Bowman. Bailey said his name was Orlando Bowman, with the last name sometimes spelled Bowerman, and the following dates are written under his picture in the Hall: “1874- 75-76-77-78 1881.”

Inside dining hall of Victor Grange.

In their first three meetings, Bailey wrote, Victor Grange members agreed to repair the Town Hall, which they had rented for five years as their meeting house. The 200 feet of spruce joists they ordered were presumably for that project.

They further voted to buy Grange regalia for 30 Brothers and 20 Sisters, one dozen fifth-edition Grange manuals and 100 letterheads. They ordered a cord of wood, and voted to pay M. D. Emery 25 cents a night “to build fires, fill oil lamps and trim wicks.”

Another early vote, Bailey wrote, was “to change the design of the seal to a Lady holding the Sickle,” instead of a man. Other early Grange seals featured a sickle; most contemporary ones show a sheaf of wheat. In 1967, the U. S. Postal Service issued a five-cent stamp showing a straw-hatted farmer holding his scythe, to honor the 100th anniversary of the National Grange.

(Sickles and scythes are both harvesting tools, hence Grange symbols. A sickle, also called a reaping hook or bagging hook, has a C-shaped blade about a foot long and a handle about six inches long; one harvesting with a sickle bends down, gathers an armful of grass or grain and cuts it a few inches above the ground. A scythe blade is only slightly curved, often over six feet long, attached to a six-foot handle with two handholds; one harvesting with a scythe stands erect and sweeps the blade along the ground, laying the grass or crop in rows. George Stubbs’ painting Reapers shows two men with sickles; Jean-Francois Millais’ painting The Reaper shows a man with a scythe.)

In January 1875, Victor Grange members started buying in bulk to sell to members cheaply: half a carload of flour; a “hogshead barreller of Puerto Rican Molasses and ½ chest of Japanese tea” (Bailey says a “hogshead barrel” was 33-1/3 gallons); and that month and in March spices, including cream of tartar. They appointed Watson Jones their agent to “sell wool for the farmers” and report at the next meeting.

They were also furnishing the Hall, buying four stands and two lamps in January and 25 chairs and a second-hand cookstove in March. In March, too, members voted to “Frame the Grange Charter in a suitable manner” and rent a “suitable instrument” (first an organ, later a piano, Bailey said).

By the first anniversary meeting, Bailey wrote, Victor Grange had 94 members. They voted to pay E. C. Jones 50 cents for stabling their horses during the anniversary celebration; and they voted to buy more regalia, three wall lamps, a hand lamp, window-curtains and “bleached cloth for tablecloths.”

They also voted to have an oyster supper and pastry at their next meeting and to buy “a suitable number” of plates, bowls, mugs and spoons.

In 1878, Bailey said, they spent $300 to buy a nearby store, which they used as a members’ co-op and, the Fairfield history says “the Grange home.”

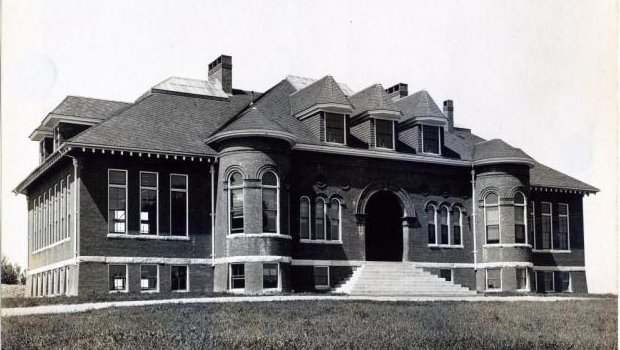

The Hall standing today was planned and built in 1902 and 1903, and the former store was attached. The Fairfield history says Maine State Grange Master Obadiah Gardiner dedicated the new building on Oct. 1, 1903.

Bailey wrote that the fourth Victor Grange Master was Orlando Bowman’s grandson, George Tibbetts. Dates under his picture are 1883-84, 1885-1889, 1901-1902 and 1905, making him the Master under whom the organization was incorporated and construction of the new Hall started.

Another piece of Victor Grange’s history is a wooden chair, with the inscription on the bottom of the seat, “March 28,”87″ [1887] Geo Tibbetts Wedding.”

On Dec. 27, 1979, Ray W. Tobey wrote Grange members a thank-you letter for the Christmas food basket they left at his house. Thinking back over the 77 years to the rainy night when he took his first two degrees as a Grange member, he wrote that “the new hall was in process of construction and the Grange was meeting in the old Town Hall just north of the present building.”

Grange women used to prepare meals for students in the one-room schoolhouse across the street. After the building was no longer used as a school, Grangers bought it and turned it into a stable.

Tobey referred to the stable as the “building in which my father went to school when he was a boy.”

The Grange Hall stands in the south angle of the intersection of Routes 104 and 139 with Route 23, facing west on Route 23 (Oakland Road). The vacant lot just south of the building is being filled for a parking lot.

The large two-story building (plus basement and attic) has one section that is almost square and one – the former store – rectangular, with the main entrance with an open porch where the buildings join. A brick chimney rises from the roof near the junction.

Bailey said the former store houses the entryway, stairs, kitchen and bathrooms. The second floor is the junior room. Junior Grangers are aged from five to 13, she said; from age 14, members are treated as adults entitled to vote in Grange business.

The 1903 Grange Hall, the square section, has the dining room on the ground floor and a meeting room on the second floor, with a stage and a painted stage curtain.

Bailey said the meeting room has a rainbow-shaped tin ceiling that is 15 ½ feet long. Records show the Grange ordered it in 1899 from Pennsylvania, paying $357. It came by boat from Pennsylvania to Boston, by train from Boston to Hoxie Siding, in North Fairfield, and by horse and buggy to Victor Grange Hall.

In the 1990s, Bailey said, the state relocated Route 23 in front of the Grange Hall, moving it so much closer that vibrations from heavy trucks damaged the building. Window panes cracked and even the granite foundation crumbled.

The Fairfield history calls the Grange Hall “the social gathering place for Fairfield Center” for many years. Bailey found records of oyster stew suppers followed by a play presented in the second-floor room; admission was 25 cents, and up to 200 people would attend.

The Grange used to meet twice a month. Programs included assigned readings, which Bailey interpreted as reading local news reports for the benefit of farmers whose spare time and reading skills were limited.

Debates were another feature. Two three-person teams would present opposite sides of an issue, without a decision whether either side won. Bailey sees this activity as educational and a chance for members to hone public speaking skills.

When a Grange member died, the Charter was draped in black for 30 days and a small group, usually three other members, prepared a Resolution of Respect. The resolutions mourned the lost members, often mentioning a specific contribution that would be missed – the delicious biscuits, the work caring for the Hall, the floral arrangements.

Bailey said Victor Grange almost collapsed in the 1990s, as interest waned nationwide and local leaders aged and fell ill. She credits former Waterville dentist Steve Kierstead (Jan. 5, 1921 – Feb. 4, 2006), whose grandfather had been an early Master, with sparking a renewal of interest.

A neighborhood canvas led to the monthly senior citizen meals that continue today. At first, short programs focused on useful information about local politics, social services and the like.

One day a member brought in a scrapbook that contained newspaper clippings and other items, to show another member how he had learned her date of birth. His action led other members to do the same, to copy and to exchange clippings and to reminisce – “some of the most fun things we’ve ever done,” Bailey said.

In recent years Victor Grange has hosted annual sessions with Window Dressers, the nonprofit group that helps people build and install energy-efficient window coverings in their houses.

Bailey said the Hall has a new furnace and is handicapped-accessible, including the restrooms and a stairlift to the second floor. She expects more programs for senior citizens, to save them the drive to Waterville’s Muskie Center or other senior centers.

Currently, Victor Grange members are raising funds for insulation and other energy-efficiency improvements for the Grange Hall.

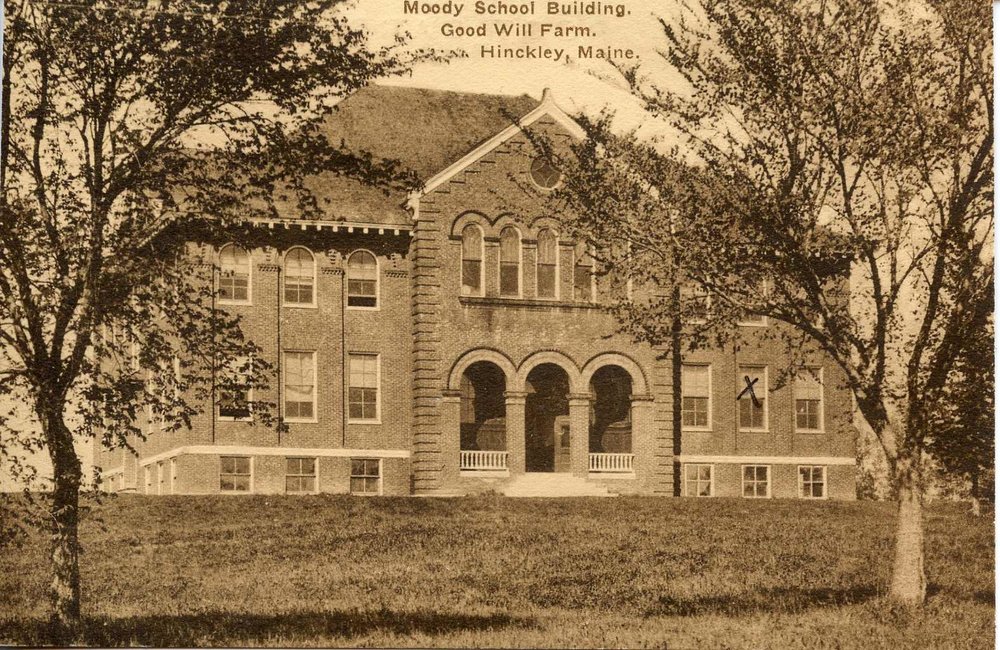

Bailey said Fairfield had another Grange organization, Hinckley Grange. Its Hall in Clinton is still standing on the east side of River Road, a short distance north of Pishon or Pishon’s Ferry, where Route 23 crosses the Kennebec River from Fairfield.

Hinckley Grange Hall is smaller than the other Grange Halls discussed, but is a typical rectangular wooden building, two stories tall with a peaked roof allowing space for one third-floor front window.

This writer has found one on-line reference to Hinckley Grange #539, in the obituary of former member Martha May Stokes (Sept. 17, 1922 – Sept. 23, 2012), who died in Kansas. The obituary says she was a Good Will High School graduate who “worked as a nutritionist for several hospitals.”

The number assigned to this Grange says it was founded in the 20th century, and Bailey reported that the collage of pictures of Hinckley Grange Masters, now part of Victor Grange’s collection of historical materials, begins in 1920 and ends in 1956.

Victor Grange schedule

Victor Grange meetings are held the second Monday of the month, with a 5 p.m. potluck supper followed by the meeting at 6. The next meeting is scheduled for June 14, the final meeting of the year for Dec. 13.

The Senor Circle meets at 11 a.m. the third Friday of the month. The next Senior Circle meeting is on May 21, and the final one for the year will be Dec. 17.

Public suppers are scheduled for 5 p.m. the fourth Saturday of each month through October. The next supper will be May 22, and the final 2021 supper will be Oct. 23.

Three special events are scheduled in the remaining months of 2021.

On Saturday, July 10, and Sunday, July 11, the Grange will host the Fairfield Historical Society’s quilt show. The show runs from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. both days; admission is $5. Grange members will provide lunches and snacks.

The Grange’s annual fund-raising tollbooth will be held in July. Readers ungenerous enough to want to know which day to avoid which road will need to consult the web.

The annual Fall Festival is scheduled for Saturday, Nov. 13.

The Fairfield Historical Society holds a barn sale from 8:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. Saturday, May 15, and Sunday, May 16, at the History House, 42 High Street, Fairfield. Items offered include furniture, glassware, jewelry, antiques, books, collectibles and more.

The Society’s website says that people attending this and other Historical Society events should wear masks and observe social distancing and other relevant Covid requirements.

Main sources

Boomsma, Walter, Exploring Traditions – Celebrating the Grange Way of Life (2018).

Fairfield Historical Society, Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Personal conversations, Barbara Bailey.