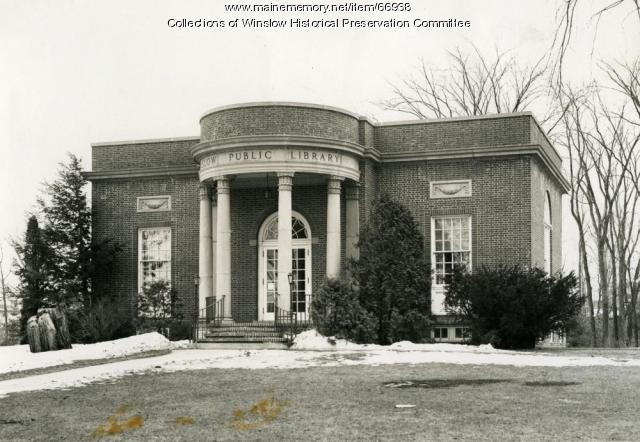

Old Winslow Library

Vassalboro, Waterville, Winslow

There is no evidence that the Town of Vassalboro had a public library before 1909, when the ancestor of the present lively institution was founded.

The 1909 association’s bylaws give it two names, the Free Public Library Association of Vassalboro, d/b/a Vassalboro Library Association. The library has always been in East Vassalboro, and the bylaws say it must remain there.

According to an essay by Elizabeth “Betty” Taylor in Bernhardt and Schad’s Vassalboro anthology, Eloise A. Hafford organized Vassalboro’s Library Association, getting advice from the Maine State Library and providing the association’s constitution.

Then, Taylor wrote, “she disappeared from the records.” Her name was crossed off the list of members in 1910.

Intrigued, Taylor did research that identified Hafford, born Sept. 30, 1860, in Massachusetts, as an early pastor at the East Vassalboro Friends Church. She was a high-school and university teacher for many years, and by 1930 was in California doing public health work, at one time serving as executive secretary of the Southern California Society for Control of Syphilis. She died in 1938.

The first Vassalboro library building was a converted summer cottage on South Stanley Hill Road, on a small lot donated by George Cates, south of the Friends Meeting House. The cottage was a gift of the Kennebec Water District and in 1914 was hauled across China Lake “on skids by four teams of horses,” according to a Jan. 25, 1971, newspaper article at the Vassalboro Historical Society.

The single-story building was about 500 feet square, according to another source. Everett Coombs built bookshelves early in 1915. Madeline Cates was Vassalboro librarian from 1910 to 1948. When the Library Association was inactive during the Depression, she continued to open it one day a week without pay, and her husband Percy provided fuel without charge.

In the 1950s, Taylor and Mildred Harris took the lead in reviving the library.

The wooden building and the book collection burned in 1979. Taylor, who was librarian for more than three decades, was again a leader in obtaining replacement books after the fire.

Vassalboro Public Library (photo: vassalboro.net)

In 1980, the library reopened in its current home, a single-story brick building at 930 Bog Road, on the west side of the village. An addition in 2000 on the back (north side) doubled the size of the building.

The Vassalboro Library receives significant town funding every year, but donations are always welcome, and are tax-deductible.

Vassalboro has at least one of the libraries in boxes described in last week’s essay. It is on the south side of the Olde Mill complex in North Vassalboro, facing Oak Grove Road, identified by the word “BOOKS” across the top.

In Waterville, the first library was started before Waterville became a town, never mind a city, according to Estelle Foster Eaton’s chapter in Whittemore’s 1902 history.

Waterville was separated from Winslow on June 23, 1802. Eaton wrote that eight months earlier, Reuben Kidder (a member of the 1801 committee chosen to petition the legislature to make Waterville a separate town) had bought 117 books from Boston bookseller Caleb Bingham, for $162.65 (with a 10 percent discount).

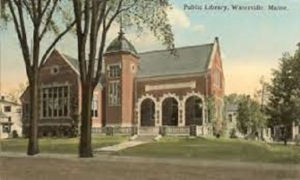

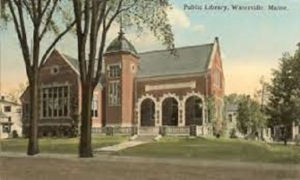

Waterville Public Library

(Caleb Bingham [April 15, 1757-April 6, 1817] was an educator, textbook writer and publisher as well as a bookseller. An on-line article by Encyclopedia Britannica editors says he directed Boston’s public library for two years without pay; donated many books to the library in his home town of Salisbury; and helped other New England town libraries. His bookstore was a gathering place for Boston teachers and liberal Jeffersonian politicians and “a focal point of agitation for free public schools.”)

The books were mostly non-fiction, Eaton wrote. Exceptions she listed were The Beggar Girl and A Fool of Quality, each in three volumes. (Welsh novelist Anna or Agnes Maria Bennett’s The Beggar Girl and Her Benefactors was published in 1797; Irish writer Henry Brooke’s The Fool of Quality was published between 1765 and 1779, originally in five volumes.)

The books reached Waterville Nov. 18, 1801. Although Kidder had ordered them in the name of the “Winslow Library,” they were labeled as belonging to “The Waterville Social Library.”

Eaton could not determine how long the library lasted, but the books ended up with Abijah Smith, one of the people who signed a note to help Kidder pay for them. Smith let the Sons of Temperance use them when that organization started a short-lived library (Eaton gave no dates).

Kingsbury wrote in his 1892 Kennebec County history that the Waterville division of the Sons of Temperance was organized Nov. 27, 1845, reorganized in 1858 and still flourishing in 1892.

In 1902, Eaton wrote, a Smith descendant owned relevant documents and, apparently, books; she wrote that when the new public library building was completed, he wanted the remainder of the Waterville Social Library to “find [a] fitting home within its walls.”

The present library organization dates from 1896, the present building from 1902.

According to Eaton and Kingsbury, there were other predecessors besides the Waterville Social Library.

Eaton lists two bookstore-based “circulating libraries.” William Hastings, who was a printer and the publisher of the Waterville Intelligencer newspaper (see The Town Line, Nov. 26, 2020) as well as a bookseller, offered “well-selected books” from 1826 to 1828. Around 1840 Edward Mathews started lending books from his bookstore; he sold the library to Charles K. Mathews, who continued it until 1874.

The Waterville Woman’s Association, founded in 1887, by 1892 had a library of 400 volumes, Kingsbury wrote, “from which 100 books are taken weekly.” (The Woman’s Association was mentioned in the Nov. 11 The Town Line.)

Eaton made the Waterville Library Association, founded in March 1873, sound like the most important predecessor of the present library. She listed the founders by initials only, except for President Solyman Heath; apparently they were all men, although Kingsbury mentioned “the cooperation of a few spirited ladies.” Association membership was $3 a year; dues were used to buy books.

The directors of the Ticonic Bank gave the library space in the bank building for 26 years, and the library was nicknamed the Bank Library, according to Eaton. A. A. Plaisted (the Waterville history’s index lists many entries for A. A. Plaisted, Aaron Plaisted and Aaron Appleton Plaisted) was librarian, “assisted within the last few years by the Misses Helen and Emily Plaisted, Miss Helen Meader and Miss Elden, now Mrs. Mathews.”

In 1892, Kingsbury wrote, the library had 1,500 books and about 30 members.

Meanwhile, a movement for a free public library began. In 1883, Eaton wrote, former resident William H. Arnold willed to the town (Waterville did not become a city until January 23, 1888) $5,000 for a public library, conditional on the town matching the gift. The town did not, and Arnold’s heirs got the $5,000.

In 1896, Lillian Hallock Campbell spent early February visiting more than 50 women to ask them to help start a free public library. On Feb. 13, the Waterville Library Association organized, with an all-female list of officers, though some men were interested in Campbell’s project.

(The first president was Mrs. Willard B. Arnold, sister-in-law of the late William H. Arnold. Her husband, the first of five generations of Willard Bailey Arnolds, founded the W. B. Arnold Company, a Waterville hardware store that closed in the 1960s.)

“Public interest was aroused,” Eaton wrote, and business leaders, including W. B. Arnold, donated generously. On March 25, another meeting organized the Waterville Free Library Association, with Mayor Edmund F. Webb president, ex officio, and a mainly male group of officers and trustees (though Lillian Campbell, Mrs. Arnold and Annie Pepper were among the dozen trustees, as was Colby College professor and future president Arthur J. Roberts).

Library supporters began collecting books and money immediately; an April 7, 1896, public notice requested donations. Books were first circulated out of Harvey Doane Eaton’s law office (he was the husband of Estelle Foster Eaton who wrote the library chapter). A five-member book selection committee recommended initial purchases.

The library formally opened Aug. 22, 1896, in a room “in the Plaisted Block.” It moved to the Haines Building in 1898. Agnes M. Johnson was the first librarian.

Eaton wrote that by May 1902 the original 433 books had become 3,088. Circulation for the year ending May 16 was 20,692. Fiction circulation had declined, but “reference work in connection with the schools” was increasing.

Funds came from individual donations; from the City of Waterville, which increased its $500 a year to $1,000 in 1902; and from the State of Maine, whose annual $50 was “supposed to cover the running expenses; although as a matter of fact it has not,” Eaton said.

After the free library opened, interest in the membership-supported Waterville Library Association declined. Eaton wrote that its 1,500 books were donated to the Woman’s Association in 1900.

The earlier reference to a pending new building foreshadowed the 1902 construction of the main part of the present Elm Street building, with a $20,000 Carnegie Foundation grant. The library’s website describes the building’s architectural style as Richardson Romanesque, similar to other area libraries in Augusta, Clinton and Fairfield. The architect was William R. Miller of Lewiston, who also designed Fairfield’s Lawrence Library (see The Town Line, Nov. 11).

The building is of brick with granite trim. The original entrance on Elm Street is approached by wide granite steps leading to three arches, and the typical tower rises beside the entrance, with a tall triple window below nine small square windows.

The original building has been renovated and expanded several times. A banner on the side of the building proclaims Waterville Public Library a “2017 Winner National Medal for Museum and Library Service.”

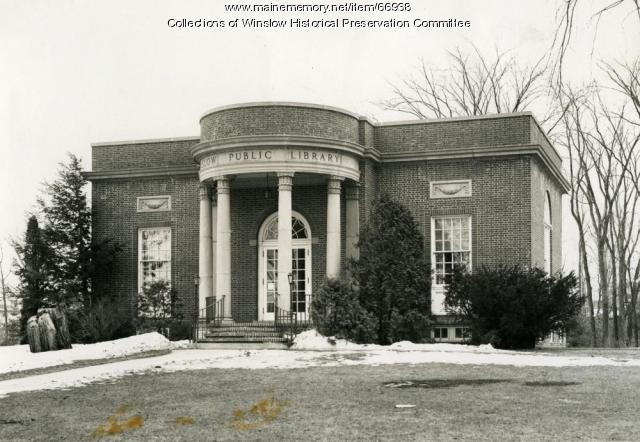

New Winslow Library

This writer has failed to find a comprehensive history of Winslow’s public library, located since the late 1980s in a handsomely-converted former roller-skating rink at 136 Halifax Street. The town web page identifies the current library as a department of the town, with a board of trustees.

For at least part of the time between 1905 and 1927, the library was on the east side of Lithgow Street, in the north end of a single-story clapboard building it shared with the town office. Historian Jack Nivison wrote that the building was between the 1926 library and the Congregational Church, set farther back from the street than they are.

A photograph shows a single-story building with a peaked roof. Above what looks like a paneled front door is a three-section semi-circular window, and above it, under the peak of the roof, a second similar one. Windows on either side have decorative shutters and window boxes.

A side door has a small rectangular window beside it. This door and two larger windows on the south side are topped with arched semicircles of what looks like stained glass.

The first librarian, Jennie Howard, served from 1905 to 1933 and was paid $52 a year. Nivison wrote that Howard was also a teacher and superintendent of schools.

The second recorded Winslow library building was built in 1926-27 on an adjoining lot donated by George Bassett, at a cost of $30,000 (the on-line source that says $3,000 must have dropped a zero).

The 1926-27 library is a two-story, flat-roofed brick building. A semi-circular columned portico the height of the building shelters an arched, glass-paneled front door. Above the columns are the words “Winslow Public Library.”

Two tall windows on the front have decorative medallions above them; the window on the south side is topped by a smaller arched window. The library now houses the Taconnett Falls Genealogy Library; its sign says it is open from 1 to 4, Wednesdays and Saturdays.

After the 1987 Kennebec River flood, the library moved to its Halifax Street home.

Nivison adds a second Winslow library with a limited clientele. He wrote that “there was a Library in the Taconnet Clubhouse, built in 1901-02. This library was open to all families who worked at H & W.”

H & W was the Hollingsworth & Whitney Paper Company mill, which operated from 1892 until, after two changes of ownership, 1997. The H & W Clubhouse also offered its employees use of pool tables, a bowling alley and a swimming pool, according to Wikipedia.

Main sources

Bernhardt, Esther, and Vicki Schad, compilers/editors, Anthology of Vassalboro Tales (2017).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Personal conversations.

Websites, miscellaneous.

by Mary Grow

by Mary Grow