Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Waterville historic district – Part 3

by Mary Grow

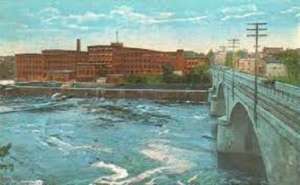

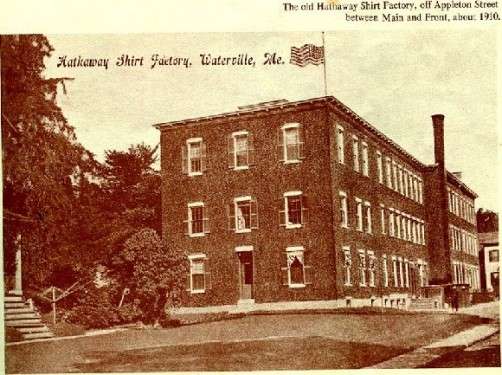

After two weeks‘ digressions, your writer returns to Waterville history, beginning with the C. F. Hathaway Shirt Company, described in Roger Reed and Christie Mitchell’s Lockwood Mill Historic District application as “an internationally known firm that originated in Waterville.” The application adds that Mill Number 2 “is the only intact industrial facility in Waterville associated with the important shirt maker.”

The company was founded by Charles Foster Hathaway, born July 2, 1816, in Plymouth, Massachusetts. In May 1840 he married Temperance Blackwell, of Waterville, in Waterville. Temperance died Jan. 19, 1888; Charles died Dec. 15, 1893. Both are buried in Waterville’s Pine Grove Cemetery.

Wikipedia says Hathaway quit school when he was 11 to work in a nail factory. When he was 15 he switched to printing, and later to his uncle Benjamin’s shirt factory in Plymouth.

The Hathaways moved to Waterville in 1843 or 1844, and Hathaway worked for different printers. In 1847 he bought out one of them for $571.47 and in April started publishing the Waterville Mail, described as “a weekly paper of four pages filled with sermons, religious homilies, and moral stories.” On July 19, 1847, he sold the business, for $475.

Ernest Marriner, who devoted a chapter in his Remembered Maine to Hathaway, explained that Waterville readers were not interested in “the religious homilies and the stern puritanical advice with which Hathaway filled his paper.”

By 1850, perhaps earlier, Hathaway was back in Massachusetts, opening the Hathaway and (Josiah) Tillson shirt factory, in Watertown. He sold out on March 31, 1853, and on April 1, according to his diary quoted on Wikipedia, agreed to start C. F. Hathaway and Company, in Waterville, in partnership with his brother George.

The first Hathaway Shirt Factory site was a one-acre lot on Appleton Street, bought for $900; the ground-breaking was June 1, 1853. Over the summer, Hathaway and two others made shirts in Hathaway’s house. By the end of October, Marriner wrote, quoting Hathaway, the factory was operating: “the working hours were 7 A.M. to 6 P.M., six days a week, with an hour off at noon” – a sixty-hour work week.

Appleton Street runs from Elm Street across Main Street to Water Street, the intersection north of Temple Street. Your writer has been unable to locate the Hathaway factory on the street (Editor’s note: It is now an apartment building on Hathaway St.). She believes the building was wooden, because Marriner described Hathaway’s 1856 negotiations over lumber for an addition.

The Hathaway Company manufactured only men’s shirts until 1874, when a line of ladies’ underwear was added. Henry Kingsbury, writing in 1892, said that since 1853, the business “has grown with the steadiness of an oak tree.” By 1902, Reuben Dunn wrote in Edwin Whittemore’s Waterville history, Clarence A. Leighton, “associated with” Charles Hathaway since 1879, was sole proprietor. (Dunn disagreed with other sources on the dates of the company’s founding and of Hathaway’s death.)

Marriner wrote that the Appleton Street factory ran for more than a century, information that matches Reed and Mitchell’s saying that Mill Number 2 in the Lockwood complex “served as the principal manufacturing plant” for Hathaway shirts from 1957 to 2002, when the business closed.

Kingsbury called Hathaway “a man of strong, original character” who valued “thorough, honest work,” held “unusually earnest religious convictions” and had “friendly and honorable” relations with his employees.

Whittemore showed Hathaway the patriot. When the first two Waterville companies mustered for Civil War service in May 1861, the 183 men and their officers marched to the Hathaway factory, “where each man was presented with a pair of French flannel shirts by Mr. Hathaway.”

Marriner called Hathaway “Poor tortured soul!” He described a man overdriven by his religious belief, seeking to be a saint but constantly bemoaning his own “depravity and deceit” and the “wickedness of…[his] natural heart.”

Hathaway wanted to convert his employees; Marriner said he required prayer at the start of each work day – “Charles Hathaway’s special brand of prayer” – until rebellion and ridicule made him lift the requirement. He felt a duty to preach to everyone he met, including those who found his “starvation wages and other business practices” not very Christian.

He was hard to do business with, being frequently sure he was cheated. Marriner described his feud with Waterville Baptist Church pastor Henry S. Burrage; and joined Whittemore’s contributors and Kingsbury in praising Hathaway’s role in establishing the Second Baptist Church in the South End.

Marriner expressed sympathy for Temperance, writing that in 1840, she could not have foreseen “the ostracism, the loneliness, the ridicule she must encounter as the wife of this man.”

* * * * * *

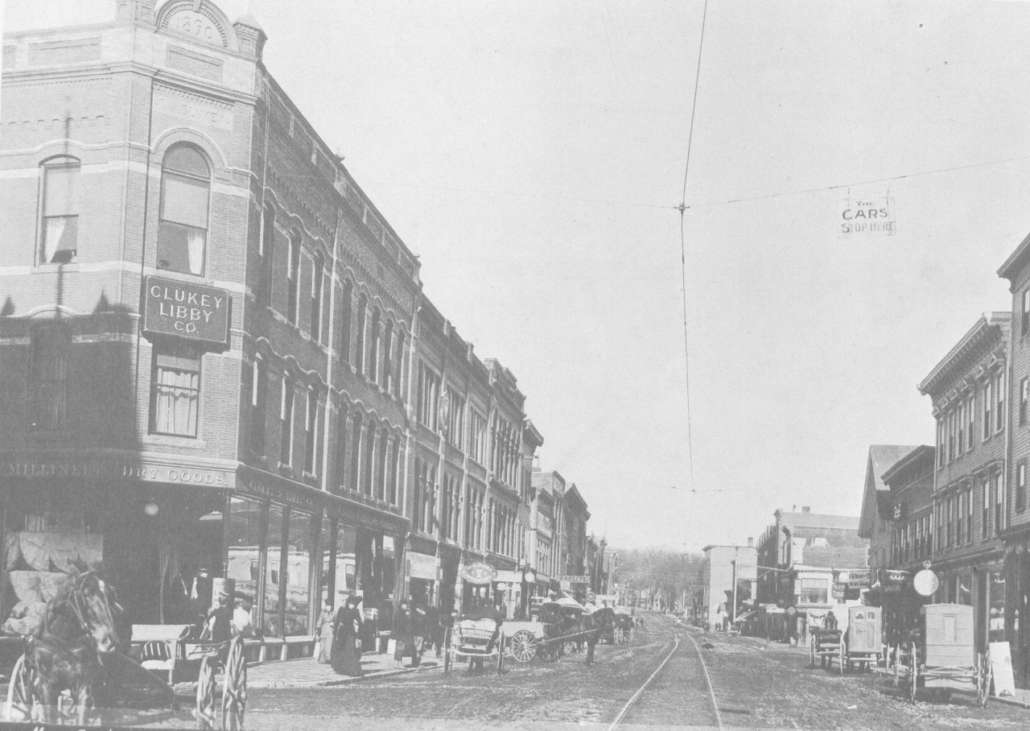

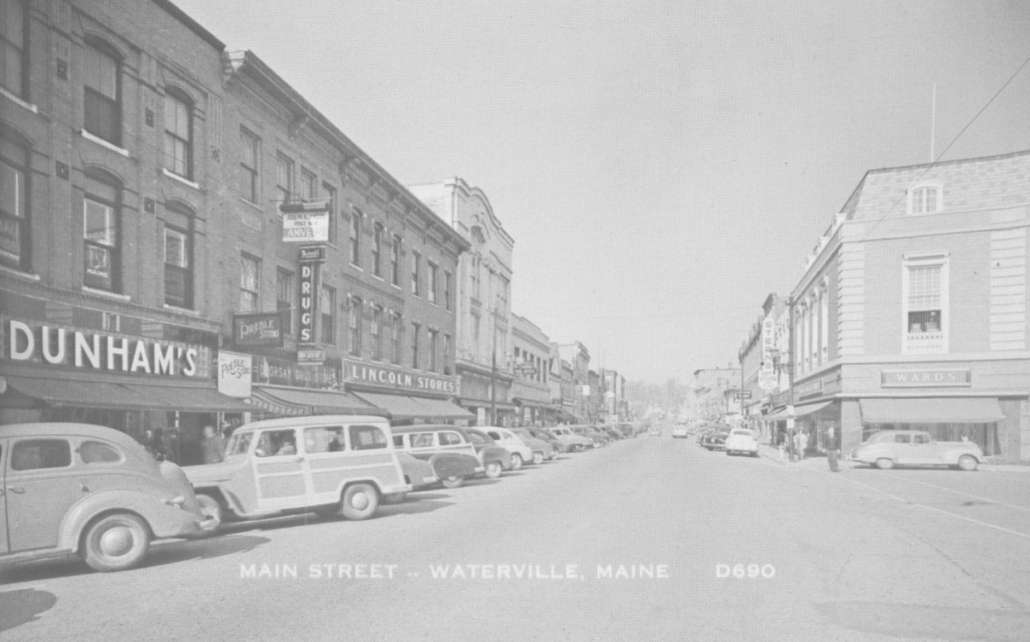

Before the interjection of the Lockwood Mill Complex and Hathaway’s shirts, readers had followed Matthew Corbett and Scott Hanson’s 2012 application for Historic Preservation listing southward on the east side of Waterville’s Main Street. Crossing to the south end of the west side of the street, Corbett and Hanson listed three buildings south of the intersection where Silver Street joins Main Street from the west. Ticonic Row was at 8-22 Main Street, separated by an alley from the newer Parent Block at 26 Main Street; next was the Milliken Block, bordered on the north by Silver Street.

Ticonic Row is described as showing Greek Revival architectural elements. Brick, four stories high, flat-roofed, it is divided into four sections with name plates from periods of separate ownership: from south to north, Gabrielli Pomerleau, Abraham Joseph, Tozier-Dow and Sarah Levine. Built in 1836, it is the district’s oldest building. Originally three stories with a gable roof, the fourth floor was added, the uppermost windows lengthened and the roof flattened in 1924.

The Parent Block, a four-story brick building with decorative brick trim, dates from 1909. The style is described as “early 20th century commercial.” Corbett and Hanson found a mid-20th-century photograph of “the original storefront with a deeply recessed central entrance between tall display windows on low wood bulkheads…. The floor of the recess was one step up from the sidewalk and appears to be a granite slab.”

The building on the south corner of Silver and Main streets, which now has Silver Street Tavern on the street floor, was in 2012 the Milliken Block, dating from 1877.

An on-line Maine Preservation website gives more history than Corbett and Hanson had space for. The site says in 1866, Waterville National Bank directors hired architect Moses C. Foster (see box) to design a bank building on the site of an earlier wooden building.

Foster’s three-story brick Italianate style building went up in 1877. Waterville National Bank failed two years later, and the building was renamed to honor banker Dennis L. Milliken.

An undated photograph on the website shows a small carriage drawn by a white horse standing on Silver Street and eight men loitering on Main Street, two leaning on hitching posts and one holding a dog on a leash. The photo shows business signs above three street doors on Main Street; the legible ones read “Mitchell Clocks & Jewelry” and “Waterville National Bank.” Smaller signs mark second-floor businesses, and on the building’s northeast corner is a large third-floor shield identifying the Odd-Fellows Hall.

This photo shows the elegant brick and stone trim and the elaborate ornaments on the protruding cornice that Corbett and Hanson described. The Milliken Block is flanked by story-and-a-half wooden buildings south on Main Steet and west on Silver Street.

Early in the 20th century, the Maine Preservation site continues, O. J. Giguere bought the building. He combined three street-level stores into one, Giguere’s Clothing Store, and “installed the “G” lead glass windows.” He also put “a name plaque on the Maine [sic] Street elevation, a common trend in Waterville as Franco-Americans started purchasing commercial blocks on the south end of Maine [sic] Street.”

The plate on the building in the photograph described above is between the second and third floors. It appears to have a name and a date.

Moses Coburn Foster

Moses Coburn Foster was born in Newry, Maine, July 29, 1827. He married Francina Smith (born in 1830), of Bethel, in 1849; they had five daughters and one son.

According to the chapter on businessmen in Whittemore’s Waterville history, Foster was educated at Rumford High School and Gould and Bethel academies. He began his career as a builder and contractor in 1846; during the Civil War he was a master builder in the Union Army’s quartermaster’s department.

The family moved to Waterville in 1874, and in 1880 he incorporated M. C. Foster and Son with his son Herbert (born in 1860, died Aug. 31, 1899).

Foster is credited with many public buildings in New England and adjacent Canadian provinces, including post offices, churches, hotels and the Maine Central Railroad Station, in Brunswick.

Francina Foster died in 1890; Moses died Sept. 21, 1906. They are buried in Pine Grove Cemetery.

Their daughter, Carrie Mae (July 18, 1862 – Dec. 24, 1953), married businessman Frank Redington in 1890. From about 1892 until Moses Foster died, the couple lived with him in the Queen Anne style house that he built, described in a 2014 Central Maine newspaper article as “the first example of this architectural style in Waterville.” The two-story wooden house is an elaborate multi-gabled structure, with a square turret and a small front porch, its fancy shingles and decorative moldings painted contrasting colors. Wikipedia says parts of the interior are original, including “the entrance hallway with formal fireplace and ‘mahogany woodwork’ and stairs.”

The Redingtons remodeled in the early 1900s, probably adding the “tin ceilings, chandeliers, and fluted Doric columns in the opening between the parlor and library.” After Frank Redington’s death in February 1923, Carrie continued to live in the house until her death.

The Foster-Redington House was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 11, 2014. Located in a secluded area near downtown Waterville, it is privately owned; anyone visiting is urged to respect the owner’s rights.

Main sources

Corbett, Matthew, and Scott Hanson, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Waterville Main Street Historic District, Aug. 28, 2012, supplied by the Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Marriner, Ernest, Remembered Maine (1957).

Reed, Roger G., and Christi A. Mitchell, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Lockwood Mill Historic District, Jan. 11, 2007.

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous

Work Health-Waterville, occupational health, will hold an open house on Thursday, September 15, 2022, from 3 – 5 p.m. at their location at 246 Kennedy Memorial Drive, Suite 202, in Waterville.

Work Health-Waterville, occupational health, will hold an open house on Thursday, September 15, 2022, from 3 – 5 p.m. at their location at 246 Kennedy Memorial Drive, Suite 202, in Waterville. The Kennebec Valley Council of Governments (KVCOG) will be offering Household Hazardous Waste Collection Days for the following locations:

The Kennebec Valley Council of Governments (KVCOG) will be offering Household Hazardous Waste Collection Days for the following locations: