Water St., Waterville, The Plains, circa 1930. Note the trolley in the center of the photo. The trolley ceased operations on October 10, 1937. Many of the buildings in this photo are no longer there. (photo courtesy of Roland Hallee)

(See part 1 of this series here.)

French-Canadians Part & other Catholics

The story of French-Canadian immigrants in the Augusta and Waterville area, as presented by the writers cited, is partly a story of separateness and discrimination evolving into cooperation and mutual respect.

* * * * * *

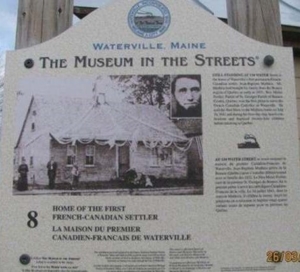

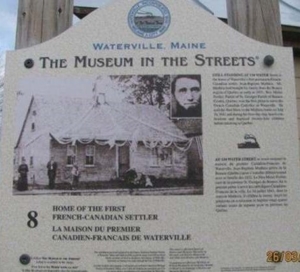

One of the stations of Waterville’s Museum in the Street in front of the home of Waterville’s first permanent Canadian settler, Jean Mathieu.

Steven Plocher’s on-line history says Québecois began to come to Waterville in the 1820s, first as temporary workers and after Jean (or Jean-Baptiste) Mathieu (or Matthieu) arrived in 1827 as permanent residents. Their numbers increased after the Kennebec Road from Québec Province was improved around 1830.

An on-line history by a writer identified as Bob Chenard, drawing on other histories of Waterville’s French-Canadian community, says in the 1820s Mathieu came as far south as Shirley (between Monson and Greenville) and started a food delivery service for lumber camps and settlers north of Bangor.

When he came to Waterville, he moved a wooden house from Fairfield to the east side of Water Street, in an area in southern Waterville called La Plains, “The Plains”. Plocher said his house served as the first French Catholic meeting house. Whittemore, in his 1902 Waterville history, said Father Fortier said the first Mass there. Neither historian gave a date.

Chenard described The Plains as the area along Water Street and side streets off Water Street. When settlement began, the land was “thickly wooded,” with occasional small clearings where livestock could graze. He said there were about 300 French families in Waterville, mostly in The Plains, by the early 1830s; your writer considers the figure of about 30 families in 1835, given by George Dana Boardman Pepper in his chapter on churches in Whittemore’s history, more likely to be accurate.

Most of the inhabitants of The Plains “were very poor,” Chenard wrote. “Some excavated and reinforced shelter in steep slopes as temporary homes. The most prosperous owned some domestic animals.”

Whittemore added an anecdote: “One of the citizens whose wealth now amounts to several tens of thousands of dollars tells how an unsuspicious cow who had strayed upon one of these turf roofs came down through it into the midst of the astonished family.”

Job opportunities Chenard listed included clearing the area that became Pine Grove Cemetery, working in sawmills and other manufactories, farming, lumbering, quarrying and brick-making. In 1855, construction of the first railroad through Waterville provided more jobs and created a second Franco-American settlement in the north end of town.

As mills and manufacturing developed in the 1860s and 1870s, job opportunities multiplied, and more French-Canadians, in Plocher’s words, left behind “their struggling farms and the British government in Québec for the economic prosperity and relative freedom found in the U.S.”

Chenard said “Waterville’s first grocery stores” were opened on Water Street in the 1860s, by “Peter Bolduc and Frederick Pooler (Poulin).” New French-Canadian stores continued to open in the 1870s; Chenard mentioned clothing and jewelry stores, and Plocher wrote,” After the first French store opened in 1862, dozens of other businesses and services followed suit: before long there were stores, doctors, dentists, lawyers, even a theater, all in the Plains.”

A successor store that Kingsbury described was John Darveau, Jr.’s, grocery, opened in 1876. Darveau was born in St. Georges, Québec, Kingsbury wrote; assisted by his brother, Joseph Darveau, and Henry W. Butler, he ran the store until he died in 1891.

The old Lockwood-Dutchess Textile Mill, on Water St., in Waterville. Now the Hathaway Creative Center. It was a mill where many Canadians went to work upon their relocation to Waterville.

The Civil War and post-war industrial development encouraged more immigration. For Waterville, Chenard wrote, the opening of the Lockwood Cotton Mill at the north end of Water Street in 1874 “attracted the greatest number of Franco-American immigrants.”

Mill owners sent representatives to the Province of Québec to solicit workers. Chenard wrote that substantial immigration continued until 1896, when the province got its first French-Canadian minister and all of Canada became more prosperous.

Kingsbury wrote that in the first six months of 1892, the Lockwood Mill produced “8,752,682 yards of cotton cloth, weighing 2,978,000 pounds. To produce these large results, 2,100 looms, 90,000 spindles and the labor of 1,250 people ten hours each week day are required.” In addition, the mill employed 50 to 75 “skilled mechanics” to keep the machinery running.

Chenard wrote that a small minority of the immigrants were doctors or other professional people, but most were extremely poor, and working in the mill was not a way to get rich. “Even the best weavers made only $1 a day”; average workers made 25 to 50 cents a day.

The mill owners helped workers find conveniently-located housing, Chenard wrote. There were “large boarding houses or small cozy homes known as ‘maison de la compagnie [company house],’ which were mostly owned by the Lockwood Company.” Another choice was an apartment in what Chenard called the Bang’s estate, “a long row of tiny red-painted houses.”

Kingsbury wrote that the French Catholic church in Waterville started as a mission served from Bangor, beginning in the 1840s. Chenard described as “Waterville’s first Catholic Church,” St. John’s on Grove Street, built by Jesuit missionary Father Jean Bapst. Pepper quoted an 1851 article from the Waterville Mail encouraging “those connected with other sects” to support the effort to provide a Catholic house of worship.

The first resident pastor was Father Nicolyn, in 1857. After two other priests, Father D. J. Halde came in 1870 and in 1871 bought a lot on Elm Street and had a larger church, St. Francis de Sales Catholic Church, built. It opened in 1874; Kingsbury said it cost $22,000, plus another $8,000 in following years (to 1892).

By 1874, Chenard said, St. John’s church had been moved to Temple Court and converted to a school. By 1902, Pepper wrote, it was a private home.

In 1880, Kingsbury wrote, Father Halde was succeeded by Father Narcisse Charland, who in 1886 bought a house for a “parochial residence” for $3,600 plus $1,000 worth of repair work. The next year the priest spent another $7,000 to build a parochial school, opened in 1888, which contributed to providing education for mill workers’ children.

In 1891 Father Charland invested $8,788 to build and furnish the Orders of Sisters Ursulines convent. Kingsbury wrote that it served “as a residence for the sisters, a boarding house for girls, and has class rooms for recitations.”

In 1892, Kingsbury wrote, there were between 450 and 480 parochial school students, 21 of them boarders. The church seated 1,100 and had two Sunday morning services, but was “too small to accommodate the worshippers from this large and growing parish, which numbers, including Winslow, over 3,000 souls.”

At that time, Kingsbury continued, Father Charland was also holding monthly services at missions in Vassalboro (see below) and Oakland.

Meanwhile, Chenard wrote that Waterville’s Second Baptist Church, also called the French Baptist Church, opened on Water Street in 1884.

Chenard went on to list a variety of French-Canadian organizations that provided social services to the French community, and cultural activities – music, drama – that spread to the entire Waterville community. Plocher added, “The Franco-Americans also introduced hockey to the city.”

Plocher and Chenard agreed that relations between French-Canadians and the rest of Waterville improved over the years. Plocher wrote, “The Anglos in Waterville were forced to adjust to the new presence, and although there was some prejudice in the Yankee population, it was not long before every business had at least one French-speaking employee.”

Whittemore and Chenard both reported much animosity between the young men of the two communities in early days. Whittemore wrote that young Anglos did not visit The Plains “with good intent,” and when young Francos came into Anglo territory “they came in bands strong enough for offense or defense, as the case might require,” sometimes adding out-of-town muscle.

The two writers further agreed that the animosity was past. “In time, it gave way to a more peaceful understanding which often resulted in warm friendships,” Chenard wrote.

Pepper’s view was that relations among adults were reasonably friendly all along. He wrote that Protestants contributed to St. John’s Chapel in the 1850s and to “larger and later” Catholic enterprises. The Mail often ran notes from the Catholic priest of the time thanking all Waterville people for “generous aid furnished especially in connection with church fairs,” he wrote.

“This liberal disposition and grateful appreciation at and from the beginning have contributed not a little to the development of that marked good will which has ever characterized the mutual relations of Catholics and Protestants, French and Americans in this town and its neighborhood,” Pepper said.

As evidence of late 19th-century integration, Chenard called Frederick Pooler/Poulin “the ‘Father’ of French politicians in Waterville,” elected selectman in 1883 and 1887, member of the first board of aldermen after Waterville became a city on Jan. 12, 1888, overseer of the poor from 1889 to 1892, board of education member in 1898-99 and legislative representative in 1906.

* * * * * *

In Fairfield, according to the Fairfield Historical Society, the first French Catholic Mass was celebrated in 1870 by Father Halde, from Waterville, “in a public hall.” By 1882 there were 104 French-Canadian families in the town, and Bishop Healy had Father Charland from Waterville put up “a small chapel on the grounds of the present church” on High Street.

The first “resident pastor” was Rev. Louis Bergoin, in 1891. The history says he thought “the chapel was too small”; it gives no date for the building of the larger church, but says Right Rev. William H. O’Connell, Bishop of Portland, visited the Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary for the first time on Aug. 18, 1901.

A Portland Press Herald article from April 27, 2015, says the building was put up in 1895. The article says “The church was closed by the Waterville-based Corpus Christi Parish four years ago at the same time it shuttered St. Theresa Church, in Oakland, and St. Bridget Church, in Vassalboro.” New owners in April 2015 planned to convert it to their home.

* * * * * *

Speaking of St. Bridget’s Church, in Vassalboro, it, too, was built primarily by and for an immigrant population of mostly mill workers, the Irish who came to North Vassalboro beginning in the 1840s to work in John D. Lang’s woolen mill. In her history of Vassalboro, Alma Pierce Robbins told the story of the church as she found it in “an anonymously-written history” from 1926.

Robbins explained that Vassalboro businessmen had already opened sawmills, gristmills and tanneries in North Vassalboro, using waterpower supplied by China Lake’s Outlet Stream. But the woolen mill required workers with different skills, so, she wrote, Lang and partners advertised “in English and Irish newspapers.”

The ads brought many Irish workers, both from Ireland and from earlier Irish communities in Boston and as far away as New York. Robbins found in the 1850 federal census a list of “new names” in Vassalboro with the countries of origin. Thirty-eight families were from Ireland; 12 were from England; four were from Canada; two were from Scotland; and John McCormack’s birthplace was given as “Atlantic Ocean.”

Many of the Irish were Catholic, and the nearest Catholic church, in Waterville, was a five-mile walk, Robbins wrote. Irish workers began departing for other mill towns where Catholic churches were nearby.

The unnamed mill agent in 1857 arranged for Mass to be said in workers’ homes. When attendees overflowed the houses, the “old Engine House Hall” became the new venue, where Waterville priests held services, at first four times a year and later once a month.

Workers continued to move away, however, and, Robbins wrote, in or a bit before 1874 mill agent George Wilkins, with the help of Waterville’s Father Halde, bought from the mill owners a lot at the intersection of Main Street and Oak Grove Road on which to found St. Bridget’s Catholic Church.

The original building was moved farther south on Main Street and served until it was destroyed by fire on Nov. 5, 1925. A new building was started the next year; the first service was Nov. 14, 1926.

St. Bridget’s Church was also sold and is now Vassalboro’s St. Bridget Center, available for rent for private and public gatherings.

Main sources

Fairfield Historical Society, Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Plocher, Stephen, Colby College Class of 2007, A Short History of Waterville, Maine

Found on the web at Waterville-maine.gov.

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902)

Websites, miscellaneous.

The following local students were named to the 2021 fall semester dean’s list at Simmons University, in Boston, Massachusetts. To qualify for dean’s list status, undergraduate students must obtain a grade point average of 3.5 or higher, based on 12 or more credit hours of work in classes using the letter grade system.

The following local students were named to the 2021 fall semester dean’s list at Simmons University, in Boston, Massachusetts. To qualify for dean’s list status, undergraduate students must obtain a grade point average of 3.5 or higher, based on 12 or more credit hours of work in classes using the letter grade system.