Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Wars – Part 3

by Mary Grow

Veterans of Waterville and Augusta

After the Revolutionary War, the demobilization of the army increased the population of the Kennebec Valley. This article and the following will describe some of the Revolutionary veterans who became part of local history, chosen more or less randomly. A visit to old cemeteries in area towns would undoubtedly add more names.

In her history of the South Solon meeting house, Mildred Cummings explained that many demobilized soldiers from southern New England came to the District of Maine for its inexpensive land. Such a move would be especially appealing to younger sons who, until after the new United States government and laws took effect, could expect the family farm to be inherited by their oldest brother.

(Solon is farther up the Kennebec River, outside the area of this study, but friends have assured this writer its meeting house is worth a visit.)

The number of central Kennebec Valley settlers, veterans and others, who came from New Hampshire and Massachusetts substantiates Cummings’ explanation.

Kingsbury added, in his Kennebec County history, that survivors of Benedict Arnold’s 1775 march to Québec remembered the Kennebec Valley as a beautiful place with land and timber resources, and some brought their families to live there.

One such was Colonel Jabez Mathews (1743-1828), according to the Waterville centennial history. Mathews went up the Kennebec with Arnold’s expedition, returned to his home town of Gray and in 1794 brought his two young sons with him to Waterville, where he was a tavern-keeper.

The Waterville history includes a chapter on military history written by Brevet Brigadier General Isaac Sparrow Bangs. After much research, he and collaborators came up with a list of more than two dozen Revolutionary War veterans with a connection to Waterville, the majority men who settled there after the war.

Ernest Marriner wrote a brief piece (reproduced on line) in which he said only two men enlisted from the small Waterville/Winslow settlement, John Cool from the Waterville side of the Kennebec and Simeon Simpson from the Winslow side.

With his essay is a photo of the memorial tablet in the Waterville Public Library listing 24 Revolutionary veterans in Waterville, most, obviously, men who came after the war. His list and Bangs’ list are similar but not identical.

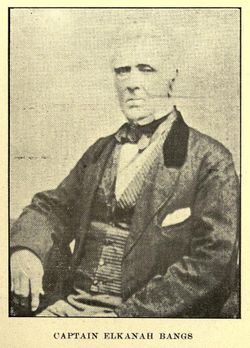

The first man Bangs mentioned (he is not on the memorial tablet) was Captain Dean Bangs (May 31, 1756 – Dec. 6, 1845), a Massachusetts native who was a mariner before the war, a privateer in 1775 and for two years beginning in 1776, a soldier in Abijah Bangs’ company in Colonel Dike’s regiment (probably Colonel Nicholas Dike, of the Massachusetts militia).

In 1802 Bangs bought “a large tract of land” in Sidney, part of it overlooking the Kennebec River, where he farmed and “reared a large family.” Waterville was his “mercantile home.”

As of the 1902 history’s publication, he and some of his family were buried in a private cemetery on his land. A memorial in the cemetery said that Dean Bangs’ father, Elkanah Bangs, was a privateer in the Revolution who was captured and died “on the Jersey prison ship at Wallabout Bay, New York, in July 1777, aged 44 years.”

(Since the memorial was erected by Dean Bangs’ grandson Isaac Sparrow, this writer concludes that the Isaac Sparrow Bangs who wrote the chapter is related to Elkanah and Dean Bangs.)

John Cool, for whom, according to Bangs and Marriner, Waterville’s Cool Street is named, enlisted in the Continental Army from Winslow on March 12, 1777, and was discharged March 12, 1780. In 1835, “on a paper” (perhaps concerning a pension?) he said he was 78 years old and had lived in by-then-Waterville for 70 years. He lived on Cool Street another 10 years, dying Oct. 5, 1845, six months after he turned 89.

Sampson Freeman, “a free man of color,” was another Continental Army veteran who served his three years, from Feb. 1, 1777, to Feb. 5, 1780, including service at Valley Forge dated June 1778 (the month the army moved out of that encampment). Freeman enlisted from Salem, Massachusetts; after the war he lived in Peru, Maine, before moving to Waterville in 1835, where he died in 1843.

Asa Redington (Dec. 22, 1761 – March 31, 1845), according to records Bangs and colleagues found, enlisted from New Hampshire in June 1778 and was discharged in December; in June 1779 re-enlisted for a year; in March 1781 enlisted for the third time.

He served in New England the first two terms, and after March 1781 went with the army to Yorktown. After Cornwallis surrendered, Bangs wrote, Redington came back north with the army to West Point, where on Dec. 23, 1783, he was discharged “without pay, and left to travel 300 miles to his home, carrying the musket he had borne during his long service.”

Redington moved to Vassalboro in 1784, married into the Getchell family, and in 1792 moved to Waterville for the rest of his life. The musket, Bangs wrote, remained in the family for years, until Redington’s oldest son gave it to the State of Maine.

Marriner added that Redington, with his father-in-law, Nehemiah Getchell, built the first dam at Ticonic Falls. Redington became a mill owner, added “a shipyard and store, and accumulated more land.”

He was the Justice of the Peace who convened Waterville’s first town meeting, held on July 26, 1802. The Redington Museum is in the Silver Street house that he built in 1814 for one of his sons.

Another prominent Waterville veteran was Dr. Obadiah Williams (March 21, 1752 – June 1799). The second of Waterville’s early physicians, he enlisted from Epping, New Hampshire, and was at Bunker Hill as a surgeon in Major General John Stark’s regiment in the Continental Army. He served for the duration of the war and came to Winslow in 1792. Several sources say he built the first frame house on the west (later Waterville) side of the Kennebec.

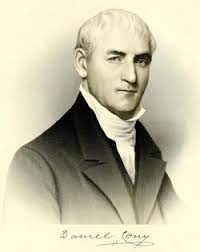

Augusta also had Revolutionary veterans among its early settlers. One of the most prominent was Daniel Cony (Aug. 3, 1752 – Jan. 21, 1842). He has been mentioned in several previous articles, notably as the founder of Cony Female Academy, opened in 1816 and closed in 1857 (see The Town Line, Sept. 2, 2021, for a summary history of the Academy and a brief biography of Daniel Cony).

A Massachusetts native, Cony was a physician practicing in Shutesbury when the Revolutionary fighting began at Lexington and Concord. North wrote in his history of Augusta that Cony enrolled in the Massachusetts militia in the fall of 1776 and joined General Horatio Gates’ army at Saratoga, New York.

North tells the story of an early adventure: a leader was needed to cross an area exposed to fire from a British battery, and he volunteered. “[T]he young adjutant at the head of his men by his wary approach drew the enemy’s fire, felt the wind of their balls, then dashed forward with his command unharmed.”

Cony and his family came to Augusta (then Hallowell) in 1778. His many public positions after the war included town clerk and selectman in Hallowell; member in both houses of the Massachusetts General Court; member of the Massachusetts electoral college when George Washington was elected to his second term as president of the United States; delegate to Maine’s 1819 Constitutional Convention; member of the new Maine legislature and of the Maine executive council; and Kennebec County probate judge.

Consistent with his enthusiasm for education, after the Massachusetts legislature chartered Hallowell Academy in 1791 (during one of his terms as a legislator), he became a member of the first board of trustees; and he was an overseer of Bowdoin College, founded in 1794, for its first three years.

On Oct, 17, 1797, in honor of the anniversary of Burgoyne’s surrender, he began building a new house. That house burned June 13, 1834. The same year he built a new one, described on a Museum in the Streets plaque as “a double brick visible on the hill behind the fort,” where he died.

In 1815, renowned portrait painter Gilbert Stuart did portraits of Cony and his wife, Susanna Curtis Cony, according to an on-line Central Maine newspapers report dated May 1918. In 1917, the Cony Alumni Association obtained permission to replicate Cony’s portrait (the original belongs to the Minneapolis Institute of Art). The resulting canvas print, framed, was hung in the Cony High School library in August 2017, according to the report.

Seth Pitts, Jr. (1754 – Aug. 22, 1846), and his younger brother, Shubael Pitts (1766-1849), were born in Taunton, Massachusetts, and both served in the Revolution. Their parents moved to Hallowell before 1781.

Seth married Elizabeth Lewis from Canton, Massachusetts. Shubael married twice, each time to one of midwife Martha Ballard’s assistants. His first wife was Parthenia Barton (1772- Sept. 4, 1794), from Vassalboro; an on-line history says Martha Ballard was “in attendance” at her death. On July 28, 1796, Shubael Pitts married Sally Cox or Cocks (born 1770).

Shubael made his living as a blacksmith, with his shop on the east side of Water Street, in Augusta. Sally “operated a boarding home for debtors in the same area,” the on-line history says.

When Augusta’s first militia company was established in 1796, Shubael Pitts was one of four captains, according to Kingsbury. (Another was Thomas Pitts, who was born too late to fight in the Revolution but was active in the War of 1812.)

The on-line history says Shubael and Sally are buried in Augusta’s Kling Cemetery (also called the Reed-Cony Cemetery, on the east side of West River Road [Route 104]). Parthenia is buried in Mount Vernon Cemetery (identified as “the old section” of Mount Hope Cemetery).

One of the veterans who spent his last years in Augusta had an unusual service record. Ephraim Leighton (January 1763 – March 15, 1851) first visited the area with his father, Benjamin Leighton, “when there were but three houses in Augusta,” according to Kingsbury. Coming from Edgecomb, they went on to Mount Vernon “by blazed trees” and settled there, Kingsbury wrote.

By May 1776, according to an on-line source, Ephraim was back in Edgecomb, because it was from there that, at the age of 11 (according to the source; 13, by this writer’s math), he enlisted in Captain Henry Tibbetts’ company in a Massachusetts regiment “and served as a waiter to Capt. Tibbetts.” He was discharged in November 1776, but despite his brief and not very military service he was later awarded a pension.

Leighton married Esther Tibbetts on Nov, 23, 1789, in Rome. He was a farmer in Rome and Mount Vernon, moved as far north as Parkman and after about 1813 lived in Augusta. He is buried in the city’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

John Chandler (Feb. 1, 1762 – Sept. 24 or 25, 1841) was another Revolutionary War veteran who came to Augusta late in life. Born in Epping, New Hampshire, third son of a blacksmith who died in 1776, in 1777, at age 15, he joined the Continental Army. He was captured by the British, escaped, was captured again in May 1779 and escaped in September. Returning to Epping, he promptly re-enlisted.

At some point he served at Fort Detroit, in what is now Detroit, Michigan, under future Secretary of War (in Thomas Jefferson’s administration) Henry Dearborn. Dearborn thought enough of the illiterate youngster to lend him money to buy a farm in Monmouth in the District of Maine, where Chandler and his wife Mary settled in 1784.

Wikipedia says “a local schoolmaster” educated Chandler. He became a successful blacksmith and prominent enough in town to be elected to the Massachusetts Senate (1803-1805) and the United States House of Representatives (March 1805 to March 1809).

Declining renomination, he became Kennebec County Sheriff in 1808 and in 1812 a major general in the Massachusetts militia. His story will continue with the history of the War of 1812.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Nash, Charles Elventon, The History of Augusta (1904).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous.

CORRECTION: In a previous version of this article, artist Gilbert Stuart was misnamed Stuart Gilbert.