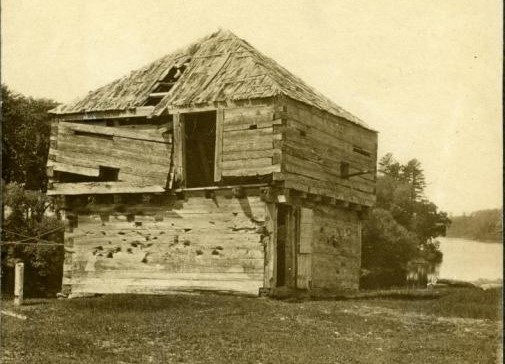

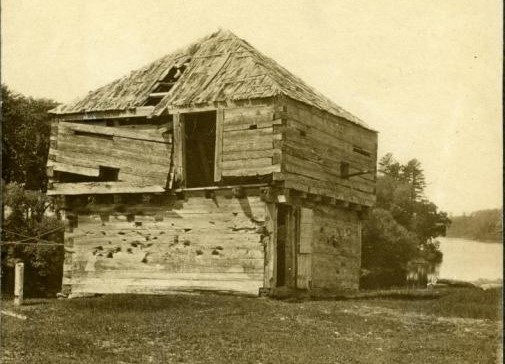

Fort Halifax in disrepair.

Important note: one of the properties described below is privately owned. Please respect the owners’ rights and privacy.

The final place along the central Kennebec River that is listed on both the National Register of Historic Places and as a National Historic Landmark is Fort Halifax, in Winslow. It was built in 1754, the same year as Fort Western, in Augusta, and for the same purpose, to protect British interests against Natives and against the French in Canada. The project was so important that Colonial Massachusetts Governor William Shirley came to the Kennebec and personally chose the site, according to Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history.

Major General John Winslow and 600 militiamen from Massachusetts built the fort on a wedge-shaped peninsula on the east bank of the Kennebec River and the north bank of the Sebasticook River. They arrived on July 25 and the first stage of construction was done so fast that Captain William Lithgow and a 100-man garrison moved in on Sept. 3.

The name honors George Montagu-Dunk (1716-1771), second Earl of Halifax. Halifax, Nova Scotia, is also named after him.

(One source calls him the British Colonial Secretary, but since, according to Wikipedia, in the 18th century that post existed only from 1768 to 1782, his influence on the American colonies in 1754 would probably have been as President of the Board of Trade, a position he assumed in 1748.)

Winslow, after whom the town of Winslow is named, had plans for a quite elaborate fort. In 1755, Wikipedia says, Captain Lithgow (by 1756 Colonel Lithgow, according to the same article) opted for a less expensive and easier to build plan, and the fort was finished in 1756.

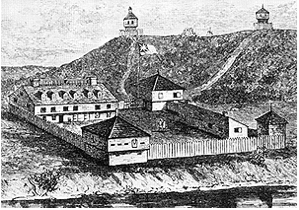

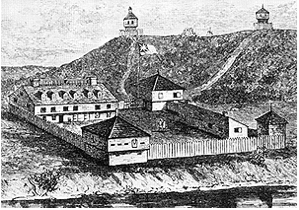

An on-line drawing of the fort in 1755 shows a palisade enclosing a square area (120 feet on a side, according to another source) with two-story blockhouses at the southeast and northwest corners. A barracks two stories high with what appear to be gable windows in a third story fills the northwest corner and half the north side. There are a smaller building that another source says contained officers’ quarters and a warehouse for supplies; an armory extends along the east side. (Kingsbury gives a quite different description.)

Roads lead to two more blockhouses on higher ground to the northeast, more than 1,000 feet away. Governor Shirley reported the first one was finished by mid-October 1754; the other was started in May 1755.

Fort Halifax, in Winslow.

Fort Halifax withstood at least two Native attacks, in the fall of 1754 and in July 1756. Wikipedia says it was abandoned and sold to a private owner in 1766.

A Winslow history on-line says when Benedict Arnold’s Québec expedition stopped there in 1775, the fort was a community meeting place, a tavern and a dance hall. Kingsbury, too, says religious services, public meetings and other events attracting a crowd were held in the fort buildings.

By 1775, another source says, surveyor Ephraim Ballard owned the property. His wife Martha joined him in 1777; she was the midwife later made famous by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s 1990 A Midwife’s Tale.

Ezekiel Pattee made his home in one of the hilltop blockhouses, and in 1775 at least one town meeting convened there. Winslow was incorporated April 26, 1771; Pattee was elected selectman that year and served until 1790. He was also town treasurer from 1771 to 1794, except for one year, and town clerk in 1771 and 1772.

After the Revolution the fort was mostly torn down. The state (until 1820 Massachusetts) used the surviving buildings to trade with Penobscot Indians, the Winslow history says. By the second half of the 19th century, only the southeast blockhouse was still standing. It was in poor condition, having been used for various agricultural purposes, including housing cows and chickens.

Kingsbury credits three residents with repairing the blockhouse in 1870. In 1873 and 1874, the Winslow history says, local residents repaired the roof and rebuilt enough of the underpinnings so the building stood straight again.

Kingsbury, writing in 1892, said the Lockwood Company had also reroofed the building. No one knew who owned the land, he said; but he urged the town to “honor itself” by restoring the fort.

In 1924 the Fort Halifax Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution acquired the structure, which then stood in the middle of a commercial area featuring fuel suppliers and warehouses, and began maintaining it and raising public awareness.

The state acquired the property from the DAR in 1965. It was designated a National Historic Landmark and added to the National Register of Historic Places on Nov. 24, 1968. In the early 1970s, Town of Winslow officials began buying adjacent land and with local donations and state and federal grants created Fort Halifax Park, opened in 1981.

The flood of April 1, 1987, swept over the park, sending the blockhouse down the Kennebec in fragments and covering the grounds with mud and debris. Work crews brought back original timbers from as far as 40 miles downriver and the blockhouse was reconstructed the next year. It is described as the oldest wooden blockhouse in the United States.

In the 2014 Winslow Town Report, then Town Manager Michael Heavener (who served from October 2006 until June 30, 2020) reported a $95,000 Land and Water Conservation grant that helped a town fund-raising committee pay for more than $193,000 in improvements to Fort Halifax Park.

Winslow has three other listings on the National Register of Historic Places. It also shares the Arnold Trail along the Kennebec (see The Town Line, Jan. 7, p. 10) and the Two-Cent Bridge between Waterville and Winslow (to be described in a later article).

The Winslow archaeological site presumably represents the oldest part of the area’s history. It was listed on the register on Dec. 27, 1990; the listing says the address is restricted, and there is no Wikipedia article corresponding to the link displayed. This writer assumes historical preservation authorities want to protect the site from unauthorized excavation.

The next oldest Winslow historic place (decades younger than Fort Halifax) is the Brick School on the east side of Route 32 (Cushman Road). Wikipedia says it was built between 1790 and 1820 – the historical marker on the building says 1806 – and is one of Maine’s oldest surviving district school buildings.

The one-room, one-story schoolhouse that served District 5 sits on a granite foundation. The ells atop the brick walls are shingled. The narrow wooden door and two windows are on the south side. Inside, Wikipedia describes a cloakroom and a fieldstone fireplace on the windowless west wall, with the rest of the building the classroom.

The school was discontinued in 1865. The building was left empty or used for storage until 1972, when the Winslow Historical Society bought it. In the 1990s, the society sponsored a more-than-$20,000 restoration project.

The society disbanded and, according to a Nov. 21, 2014, Central Maine Newspapers story by Evan Belanger (found on line), ownership of the building went back to the grandchildren of long-time owner Francis Giddings.

On Oct. 7, 2014, Town Manager Heavener reported to the town council that the Giddings were willing to convey the building to the town. Belanger described councilors’ and school officials’ deliberations: could they afford to maintain the building? And if they could, what use would it be?

Belanger wrote that immediate repairs were estimated to cost up to $13,500, and annual maintenance $1,000 to $2,000. He quoted some town and school officials who wanted the town to buy it and use it as a living history site to educate schoolchildren and adults.

Early in December 2014, Belanger reported, the Winslow Council voted unanimously to take ownership of the former school and to forgive $200 in back taxes. The Winslow Historical Preservation Committee, a town body that succeeded the historical society, assumed responsibility for the property.

The little red brick schoolhouse.

The brick schoolhouse was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977.

The final Winslow property listed on the historic register and in Wikipedia is what those sources call the Jonas R. Shurtleff house. It is listed in the on-line Winslow encyclopedia and other sources as the Jonas B. (for Ball) Shurtleff house; this name is almost certainly the correct one.

Shurtleff bought the former Cushman property, about 13 acres, on the west side of what is now Route 201 (Augusta Road) in 1849. The previous owner was Rev. Joshua Cushman, a Revolutionary War veteran. One source says Cushman settled in Winslow in 1784. Kingsbury lists him among the early settlers along the Kennebec south of the Sebasticook, but not among 1791 resident taxpayers, and says Cushman graduated from Harvard in 1787, was ordained in Winslow on June 10, 1795, and died early in 1834.

Shurtleff built his house between 1850 and 1853, and it is little changed on the outside since. The tall wooden house has a granite foundation, vertical siding, and a gable roof. Windows, the open front porch and the gables are decoratively trimmed. Originally painted brown, it is now red with white trim.

Wikipedia called the architectural style “vernacular Gothic Revival.” In architecture, “vernacular” means a style that uses local materials, reflects local ideas and often does not require a professional architect.

In a brief on-line piece written in 2017 for MaineHomes newsletter, Julie Senk, of Portland, calls the house a Carpenter Gothic cottage and says Carpenter Gothic was a version of Gothic Revival tailored to local taste.

Jonas Ball Shurtleff (June 11, 1805 – Dec. 31, 1863) was a New Hampshire native who moved to Beaver, Pennsylvania, in 1826. He published a newspaper called the Tioga County Patriot until 1844 and served on the Pennsylvania Governor’s council and staff. He came to Waterville in 1847 and ran a bookstore for two years; then he was a traveling representative for textbook publishers until his death. He is buried in Fort Hill Cemetery, on Halifax Street, in Winslow.

In 1854 Shurtleff transferred title to the house to his second wife, Mariette or Marietta. He lived there until his death, and she until her death in 1903. When Kingsbury finished his Kennebec County history in 1892, Mariette and her two sons, Albert Thomas and Warren Ames, then aged 45 and 43, respectively, had a farm and orchard.

The Shurtleff House.

Wikipedia says the Shurtleff house has always been “a local landmark and minor tourist attraction.” It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

The Maine Historic Preservation list includes one former Winslow listing that has been removed. Winslow’s Shrewsbury Round Barn was listed on the National Register Feb. 19, 1982, and was removed Jan. 15, 2004, because it no longer existed. The listing places the barn at 109 Benton Avenue, which, according to Google maps, is on a slope a little south of the town office – an unlikely place for a farm.

However, the Vintage Aerial on-line listing shows a 1964 aerial photo of a farm with a large round barn at the intersection of Benton Avenue and Roderick Road, on flat land about three-quarters of a mile north of the town office. Residents’ comments accompanying the photo say the farm belonged successively to James Lowell Deane; to his son-in-law, Donald Corbett; and to the Charles Auger family. It burned in 1991, and comments suggest suspicion that the fire was not accidental.

Sources:

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed. Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Websites, miscellaneous.

To the editor:

To the editor: