REVIEW POTPOURRI: 10th former President John Tyler

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates

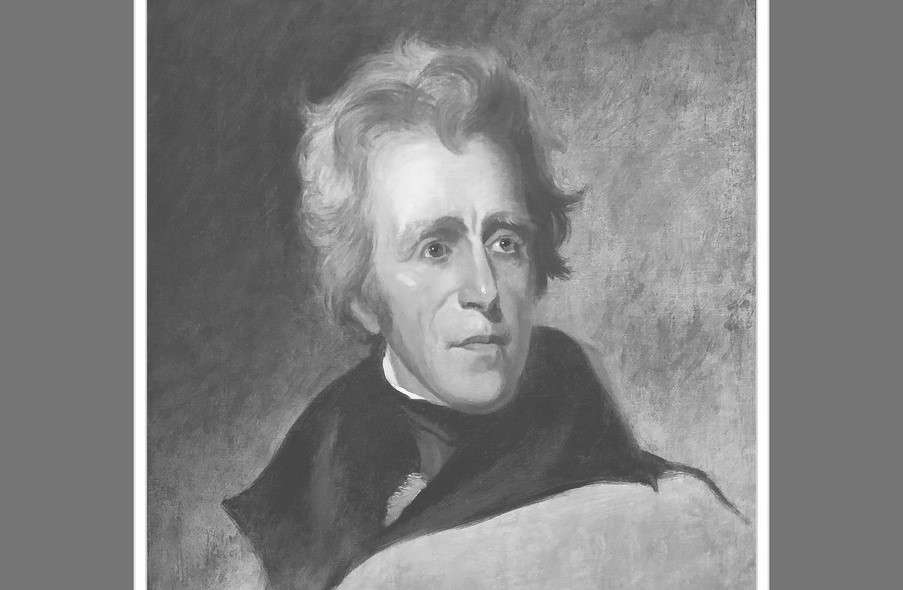

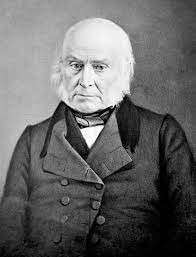

John Tyler

The 10th former President John Tyler (1790-1862) did forge important treaties with Great Britain and China and brought about the admission of Texas as a state. But he had a stubborn streak in his independence and refusal to compromise on his own principles, which quickly led to the resignations of every member of his cabinet, except for Secretary of State Daniel Webster.

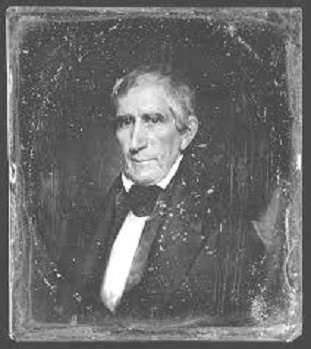

The easy going William Henry Harrison had reluctantly accepted Tyler as a running mate , the vice-president had thought that he could spend most of his time on his Virginia plantation while showing up a few months a year to preside over the Senate and both gentlemen could stay out of each other’s hair. Fate intervened with Harrison dying of pneumonia one month after taking office.

Congress was so alienated by Tyler’s incorrigible personality that they fought him on just about every piece of domestic legislation, even refusing to allocate funds for much-needed renovations in the White House.

Tyler was married twice. His first wife Letitia Christian Tyler (1790-1842) bore him eight children and, three years before her husband assumed the presidency, had suffered a stroke and was confined to a wheelchair.

Her daughter-in-law Priscilla described her as follows:

“She must have been very beautiful in her youth, for she is beautiful now in her declining years and wretched health. Her skin is as smooth and soft as a baby’s; she has sweet, loving black eyes, and her features are delicately moulded; besides this, her feet and hands are perfect; and she is gentle and graceful in her movements, with a most peculiar air of native refinement about everything she says and does. She is the most entirely unselfish person you can imagine…”

Letitia died on September 10, 1842. Daughter-in-law Priscilla assumed White House hostess duties for most of Tyler’s term and the parties were a smashing success, the guest lists guided by a very generous open door policy that included Tyler’s political enemies.

One such occasion proved to be a personal embarrassment for the hostess when Secretary of State Daniel Webster was in attendance, as described in a letter to her sisters:

“…at the moment the ices were being put on the table, everybody in good humor, and all going ‘merry as a marriage bell,’ what should I do but grow deathly pale, and, for the first time in my life, fall back in a fainting fit! Mr. Webster… picked me up…and Mr. Tyler (Priscilla’s husband Robert), with his usual impetuosity, deluged us both with ice-water, ruining my lovely new dress, and, I am afraid, producing a decided coolness between himself and the Secretary of State….”

A frequent guest, former First Lady Dolley Madison, happily made herself available at Priscilla’s request for consultation on details.

On February 28,1844, President Tyler and approximately 350 guests were upon the propeller-driven steam frigate Princeton for a cruise up the Potomac where a specially mounted gun, the Peacemaker, had been fired for demonstration purposes during these festivities. One final shot had been requested, the weapon exploded and eight men were killed .

Among those casualties were Daniel Webster’s replacement as Secretary of State Abel P. Upchurch (after three years of loyalty to Tyler, Webster resigned because of the controversy around the annexation of Texas which then allowed slavery, an issue on which he and President Tyler disagreed. However, both men had a high regard for each other, despite their differences on this issue and others); Secretary of the Navy Thomas W. Gilmer; and Tyler’s good friend David Gardiner, whose 24-year-old daughter Julia was engaged to the president .

The president was below deck with Julia when the explosion occurred, who fainted in his arms when the tragedy occurred.

They were married the following June, the gaiety of White House social occasions was sustained during the remainder of Tyler’s administration and, for Julia, her husband could do no wrong.

She gave her husband seven more children and, when James Knox Polk became the chief executive, the couple retired to Sherwood Forest, a spacious plantation Tyler purchased for his wife that was located on the James River, in Virginia, and equipped with all the creature comforts then existing.

The magnificent parties continued with winter balls, infinite numbers of teas and lavish dinners.

In 1861, Tyler attended a Peace Conference in D.C. in a futile attempt to allay North/South tensions; he then returned to Virginia, sided with the Confederacy, was elected to the Confederate Congress and was ready to serve when he died in January 1862; his death was unnoticed in Washington and he remains the only former president not laid to rest under an American flag.

His widow outlived him by 27 years and died, at age 69, in 1889.

Tyler is also the earliest former president to have a grandchild still living, a 94-year-old gentleman unfortunately suffering from dementia and in an assisted living institution, also in Virginia.