China’s Anita Smith cited by statewide group

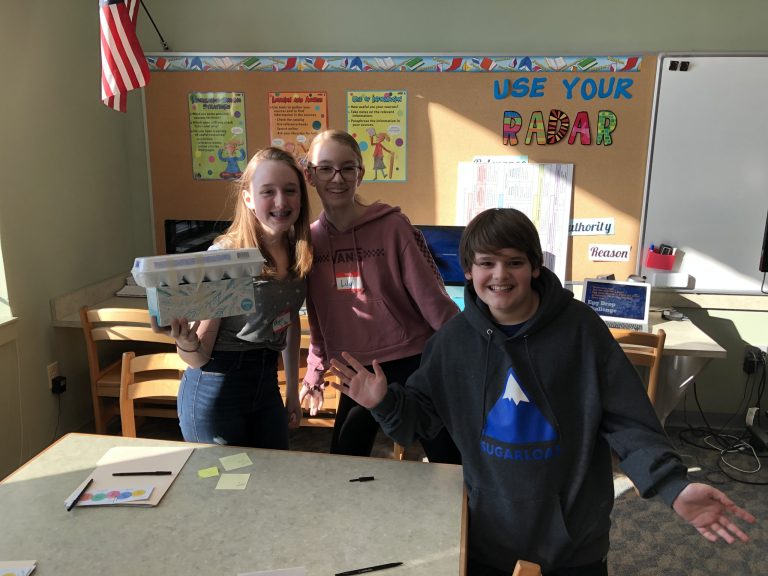

From left to right, is Olivia Grist, executive director of the Maine Environmental Education Association, Anita Smith, and Linda Woodard, of from the Maine Audubon Society. (contributed photo)

Anita Smith, of China, was recently presented the 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Maine Environmental Educators Association at the Maine Audubon headquarters located at Gilsland Farm, in Falmouth. This award recognizes Mrs. Smith’s many years of service promoting the benefits and rewards of being outside in nature. She has worked all over the state with schools, teachers, children, families, colleges and anyone curious about the wonders that can be found in nature.

Anita Smith is best known locally for her years of teaching in the China schools and her on-going work with the China School Forest, an “outdoor classroom” with trails and learning stations owned by the Town of China.

Along with her work in China, she is a facilitator and board member of Maine’s Project Learning Tree (PLT). Maine PLT uses the forest and trees as “windows” into the complex natural world. As a facilitator, Smith has presented a number of workshops to teachers throughout the state using the Project Learning Tree’s preK-12 curriculum materials. Helping educators make the connections to move a classroom from inside four walls to outside into the real world.

She is a trained Maine Master Naturalist. Her training increased her knowledge of the natural world so she could better help others understand the inner workings of nature. She currently is a mentor to this year’s participants in the Maine Master Naturalist program. This training enables participants to volunteer as teachers of natural history and encourage the stewardship of Maine’s natural environment.

Smith is a true believer of the importance of connecting not only children with the natural world but everyone. Knowing that as we become more knowledgeable of the inner workings of our natural world we become better stewards of the Earth and can make decision based on our experiences.

Congratulations to Anita Smith on her 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Maine Environmental Educators Association recognizing her commitment to provide positive experiences for our community and giving us with a sense of wonder of our natural surroundings.

Come help Maine’s only Leap Year town celebrate its anniversary! All the fun begins on Wednesday, February 26, with Saturday, February 29, being a day filled with family friendly fun! The schedule of events looks like this:

Come help Maine’s only Leap Year town celebrate its anniversary! All the fun begins on Wednesday, February 26, with Saturday, February 29, being a day filled with family friendly fun! The schedule of events looks like this: