Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Notable citizens

by Mary Grow

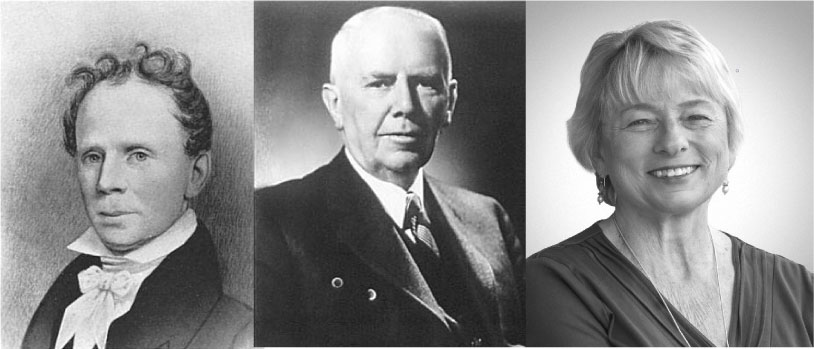

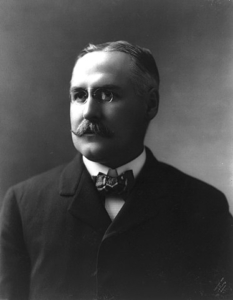

James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine was born Jan. 31, 1830, in West Brownsville, Pennsylvania. The town is on the Monongahela River south of Pittsburgh; Interstate 40 now runs through it. The current google map shows an area called Blainsburg between the river and the interstate, a major road called Blaine Hill Road and a Blainesburg Bible Church. The 2010 census reported a population of 992; by 2018, it had decreased to 965.

Blaine’s parents were middle-class. His father graduated from Washington College (now Washington and Jefferson College) in Washington, Pennsylvania, less than 30 miles from West Brownsville. Blaine entered Washington College when he was only 13 and graduated as class salutatorian in June 1847, when he would have been 17.

From graduation until 1853, Blaine considered law school without getting there. In the late 1840s and early 1850s (different sources give different dates) he taught at Western Military Institute in Georgetown, Kentucky (mathematics and ancient languages) and later at the Pennsylvania Institution for the Instruction of the Blind in Philadelphia (science and literature).

While in Kentucky, Blaine met Harriet Stanwood, born in Augusta, Maine, Oct. 12, 1827. She was a graduate of Cony Academy and a Massachusetts girls’ school and was teaching at a Kentucky girls’ school about 10 miles from WMI. They were married June 30, 1850, in Pittsburgh. Their first son, Stanwood, was born in 1852 in Augusta during an extended visit with Harriet’s family; he died at the age of three.

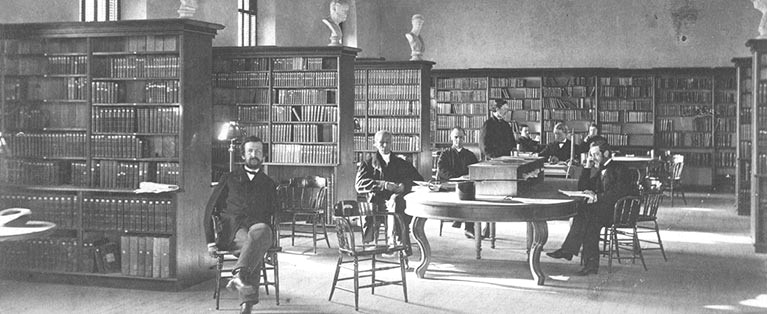

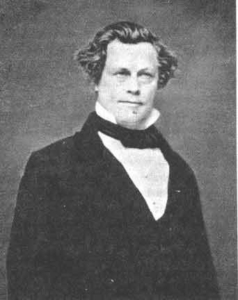

Blaine’s Augusta connection led in 1853 to his being offered positions as co-owner and co-editor of the “Kennebec Journal,” the Augusta newspaper founded as a weekly in 1825 by Luther Severance, who was retiring. Ernest Marriner wrote in his “Kennebec Yesterdays” that the paper became a daily in 1870; it is still published six days a week.

Co-owners Blaine and a minister named John L. Stevens had been Whigs, but as the Whig Party dissolved and the Republican Party became its successor, they used their paper to promote the new party. Blaine had to borrow money from his wife’s family to buy his share of the paper; it soon became profitable enough to let him start building a comfortable fortune with investments in Pennsylvania and Virginia coal mines.

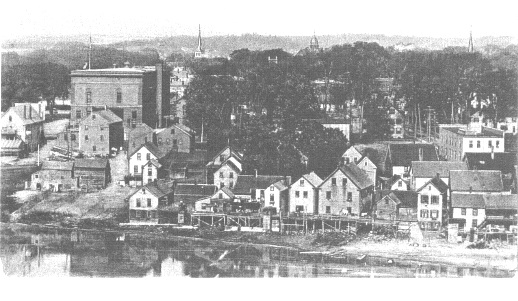

Although Blaine deserted the “Kennebec Journal” in 1857 to edit the “Portland Daily Advertiser” for almost three years, he kept his residence in Augusta and entered Republican politics from the city, which had been Maine’s capitol since 1827.

In June 1856 Maine Republicans sent Blaine to the first-ever Republican National Convention, held in Philadelphia. The convention nominated John Fremont of California for president, over Blaine’s more conservative preference, Supreme Court Associate Justice John McLean of Ohio. Fremont lost the general election in 1856 to James Buchanan.

Two years later Blaine ran successfully for the Maine House of Representatives. He was re-elected annually through 1861, serving as Speaker of the House in 1861 and 1862.

In 1862 Blaine ran successfully for the United States House of Representatives, where he served until July 1876. In the spring of 1869 he was elected Speaker of the House for the 41st Congress, a position to which he was re-elected twice. Republicans lost the House majority in the 1874 elections.

The first consideration of Blaine as a presidential candidate was at the 1872 Republican national convention. Blaine was at that time not interested and supported Ulysses Grant’s re-election.

In 1876 Blaine was again suggested for the Republican presidential candidate, and this time he sought the nomination. After a drawn-out contest at the national convention, he lost to Rutherford B. Hayes, who went on to win a contested election. It was at the 1876 convention that an Illinois Republican referred to Blaine as a “plumed knight,” a nickname that lasted for years.

In June 1876, Lot Morrill, one of Maine’s two United States Senators, joined President Grant’s Cabinet as Secretary of the Treasury. On July 10, 1876, Maine Governor Seldon Connor appointed Blaine to succeed Morrill in the Senate.

Blaine was again a leading presidential contender in 1880, and lost to James A. Garfield, who was elected president. Garfield chose Blaine as his Secretary of State; Blaine therefore resigned from the Senate on March 4, 1881. When Garfield was assassinated on July 2, 1881, in Washington’s Sixth Street railroad station, Blaine was with him, seeing him off on a summer vacation. Vice-President Chester Arthur succeed Garfield and chose a new Secretary of State effective in December 1881.

In 1884 Blaine was finally nominated as the Republicans’ candidate for president, running against Grover Cleveland. Cleveland won the popular vote by a narrow margin, the electoral college vote handily.

Part of the reason for Blaine’s loss in 1884 goes back to his 1850s interest in investing money to make more money. In the 1870s, his reputation was damaged by repeated accusations of bribery and other illicit financial actions. In 1876, opponents obtained business-related letters that Blaine had asked the recipient to burn.

One result was the Democrats’ still-famous political chant from 1884: “Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, continental liar from the State of Maine: Burn this letter!”

The Republican men who gathered daily at the general store in South China, Maine, in Rufus Jones’ youth admired Blaine greatly. Jones wrote in “A Small-Town Boy” (one of his autobiographical works referenced in the July 30 “Town Line” story about his early life) that the store-sitters repeatedly elected Blaine president in the 1870s and 1880s, though they never got the rest of the country to agree with them.

One day, Jones wrote, the great man came from his Augusta home to South China, stopped at the store and asked the Quaker boy to water his horse. After Jones fetched the water, Blaine had a brief conversation with him about the weather and the scenery, making the youngster a temporary neighborhood celebrity.

Blaine had started writing his two-volume memoir, “Twenty Years of Congress,” in the late 1870s. After the fall election in 1884, he used his forced retirement to complete the second volume and to visit Europe with his wife and daughters.

As the 1888 election neared, there was yet another movement, in Maine and nationally, to nominate Blaine for president. He absolutely declined. Republican Benjamin Harrison was nominated, partly because Blaine supporters believed Blaine liked Harrison, and became president.

Harrison promptly appointed Blaine as Secretary of State again; he served from 1889 until he resigned for health reasons in June 1892. At the 1892 Republican convention he yet again received votes for the presidential nomination, despite his repeated statement that he would not accept it.

James G. Blaine died in Washington, D. C., on Jan. 27, 1893. Three of his and Harriet’s children died earlier that decade, Walker and Alice in 1890 and Emmons in 1892.

During Blaine’s years in the District of Columbia, he owned a house there, but maintained his Augusta ties. In 1862 he bought the house that is now the Blaine House, official residence of Maine’s governor, as a birthday present for Harriet. After his death, she moved from Washington to the Augusta house and spent much of her last decade there. She died July 15, 1903.

Harriet Blaine’s will left the Blaine House to the three surviving children, son James and daughters Harriet (Beale) and Margaret (Damrosch), and two grandsons (sons of daughter Alice Coppinger). The younger Harriet’s husband Truxton Beale bought out the other heirs and gave the house to his son, Walker Blaine Beale. After Walker Beale was killed in France in 1918, his mother (who lived until Jan. 28, 1958) gave the building to the state as a memorial and governors’ mansion.

James and Harriet Blaine were first buried in Washington’s Oak Hill Cemetery, by Walker’s and Alice’s graves. After the State of Maine created the Blaine Memorial Park in Augusta in 1920, they were reburied there. The three-acre park is beside Forest Grove Cemetery; visitors can get to it from the cemetery or from Blaine Avenue, which runs from Western Avenue to Winthrop Street along the north side of the cemetery.

Main sources

Web sites, miscellaneous

Our teacher, Mrs. Jones, knew each student, as she had seen us grow up from cute children to brats as we got older. Nowadays, they would call myself and my brother troublemakers. We just had busy hands and minds so the teacher gave us projects to do.

Our teacher, Mrs. Jones, knew each student, as she had seen us grow up from cute children to brats as we got older. Nowadays, they would call myself and my brother troublemakers. We just had busy hands and minds so the teacher gave us projects to do.

by Elizabeth Byrd Wood

by Elizabeth Byrd Wood