Up and down the Kennebec Valley: China – Palermo

by Mary Grow

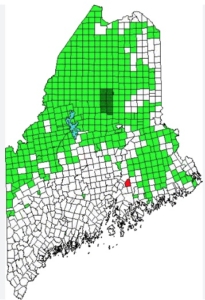

The next town north of Windsor is China, which, like Windsor, began life as a plantation and did not acquire its present name for some years after the first Europeans settled there.

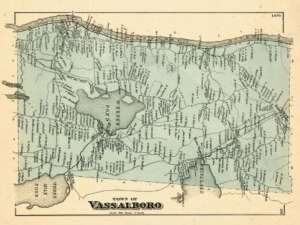

A dominant feature of the town is what is now China Lake, earlier known as Twelve Mile Pond because it was 12 miles from Fort Western and the Cushnoc settlement. China Lake is almost two lakes. A long oval east basin runs north-south, with the main inlet at the north end. A short channel two-thirds of the way down the west shore, called the Narrows, connects to a ragged sort-of-oval west basin, with its western third in Vassalboro.

The outlet is at from the northwest side of the West Basin. Outlet Stream runs north through Vassalboro and Winslow to join the Sebasticook River before it flows into the Kennebec River.

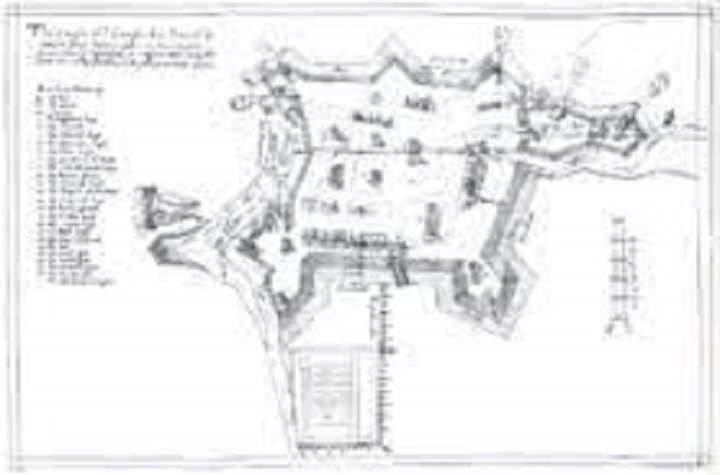

Henry Kingsbury, in his Kennebec County history, wrote that in the fall of 1773, the Kennebec Proprietors had surveyors Abraham Burrell (Burrel, Burrill) and John “Black” Jones “lay out 32,000 acres [50 square miles], including the waters” into approximately 200-acre farms.

Jones spent the winter of 1773-74 in Gardiner and finished the survey in the spring, creating a March 19, 1774, plot plan that Kingsbury reproduced. It is usually called John Jones’ plan, without mention of Burrell; and the Proprietors, Kingsbury said, named the area Jones Plantation.

In Gardiner, Jones met Ephraim Clark (July 15, 1751 – Oct. 20, 1829), from Nantucket, youngest son of Jonathan Clark, Sr., (1704 – 1780) and Miriam (Merriam, to Kingsbury, or Mirriam) (Worth) Clark (1710 – 1776). Ephraim came to Jones’ surveyed area in the summer, took up almost 600 acres toward the south end of the lake’s east shore and built a house.

Following Ephraim to China came his older brothers Jonathan, Jr. (1735, 1736 or 1737 – 1816), and his wife, Susanna (Swain, 1751-1821, according to on-line sources, or Gardiner, according to Kingsbury, who gave no dates); Edmund (1743 – 1822); and Andrew (1747 – 1832 or 1842); his sister and brother-in-law, Jerusha (Clark) Fish (Dec. 20, 1732 – Sept. 25, 1807) and George Fish (Aug. 15, 1746 – unknown; he died at sea on his way to England, sources say); and his parents.

Jonathan, Jr., and Edmund settled in 1774 on adjoining farms on the west side of the lake, south of the Narrows. Andrew chose a lot at the south end. The Fishes settled farther north on the east shore, near the present Pond Meeting House on Lakeview Drive. Jonathan, Sr., and Miriam reportedly lived with Ephraim.

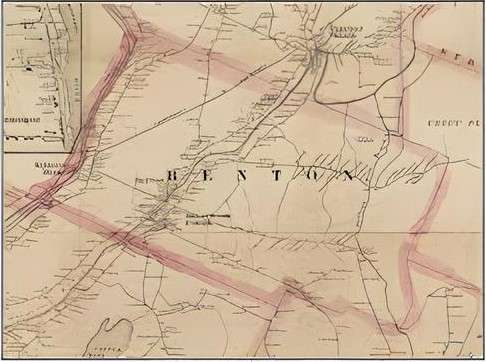

In 1774, the southern part of China, about nine-tenths of the present-day town, was incorporated as Jones Plantation, almost certainly named for surveyor John Jones (though the China bicentennial history says “some sources mention an early settler named Jones from whom the name was taken”).

Settlement expanded over the next two decades. On Feb. 8, 1796, the bicentennial history says, the Massachusetts legislature made Jones Plantation a town named Harlem. The history quotes a source saying the origin of the name was the Dutch city of Harlem, but adds there is no evidence to support the statement “and no evidence of a Dutch settlement in China.”

Wikipedia says “Massachusetts legislative member Japheth Wasburn [sic] submitted the name.” This statement is incorrect; Japheth Coombs Washburn provided the name China 22 years later (see below), but he did not move to the area until 1803 or 1804.

The northern end of today’s China was first called Freetown Plantation. Various boundary adjustments in 1804, 1813 and 1816 moved the acreage temporarily to Fairfax (later Albion), then added land from Fairfax and Winslow.

Harlem, like other early towns, was headed by an elected board of three selectmen, assisted by a town clerk, a town treasurer and other officials as needed. At Harlem’s first town meeting, held at 11 a.m., Monday, March 28, 1796, Ephraim Clark was elected one of the three selectmen (with Abraham Burel and James Lancaster), and also the treasurer and the surveyor of lumber.

On Feb. 18, 1818, the Massachusetts legislature approved an act creating a new town that combined northern Harlem, from about the middle of present-day China, with parts of Fairfax and Winslow. The bicentennial history offers only a surmise, not a definitive explanation, of the action: southern Harlem residents were dominant in town government and northerners wanted more say.

Japheth Coombs Washburn, who lived in the pending new town and was Harlem’s legislative representative in Boston, was directed to have the new town named Bloomville. However, a town up the Kennebec had been named Bloomfield since February 1814, and that town’s legislative representative objected to so similar a name, fearing mail delivery problems.

Washburn, on his own to name the new town, chose China because it “was the name of one of his favorite hymns and was not duplicated anywhere else in the United States.”

(Bloomfield was combined with Skowhegan in 1861. An article by William Hennelly, chinadaily.com.cn, reproduced in the June 15, 2017, issue of The Town Line, says China, Michigan, was named in 1834, the name proposed by explorer Captain John Clark’s wife, who was a China, Maine, native; and China, Texas, began as China Grove [of chinaberry trees] in the 1860s.)

After another four years of contention, during which Harlem voters tried first to reclaim and then to join China, in January 1822 the by then Maine legislature combined the two, creating the present Town of China. There were minor boundary adjustments with Vassalboro in 1829 and with Palermo in 1830.

* * * * * *

Two Palermo historians offer three versions of the naming of that town, northwest of China (thus one tier of towns farther from the Kennebec River).

The earlier was Milton E. Dowe, whose 1954 history begins with Great Pond Settlement (sometimes Sheepscot Great Pond Settlement), so called because it was “near the Sheepscot Great Pond.” This large lake in the southern part of present-day Palermo is on the Sheepscot River.

(For the origin of the name “Sheepscot,” see the history article in the Feb. 22, 2024, issue of The Town Line.)

The second historian, Millard Howard, writing in 1975 (second edition finished in September 2014 and copyrighted in 2015 by the Palermo Historical Society), praised Dowe’s history, without always agreeing with it.

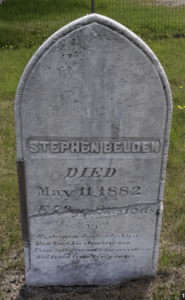

About 1778, Dowe wrote, Stephen Belden “rode through the wilderness on horseback with his Bible under his arm” and built a log cabin to found the settlement. His son, Stephen, Jr., born on the spring of 1779, and daughter, Sally, born in the fall of 1880, were the first boy and girl, respectively, born in Palermo.

Grave of Stephen Belden, who is buried in Dennis Hill Cemetery, on the Parmenter HIll Road, in Palermo.

Howard said Stephen, Sr., arrived in 1769, accompanied by his wife, Abigail (Godfrey) Belden (1751 – 1820), and an older son named Aaron. He dated Stephen, Jr.’s, birth to 1770, and said the couple had three more daughters after Sally.

“Probably,” Howard said, Stephen, Sr., was a New Hampshire native; and before coming to Great Pond he might have lived in nearby Ballstown (now Jefferson and Whitefield). Find a Grave says Stephen, Sr., was born Feb. 14, 1745, in Hampshire County, Massachusetts. He died June 15, 1822; he and Abigail are buried in Palermo’s Dennis Hill cemetery, on Parmenter Hill Road.

Dowe wrote that the 1790 census listed 26 families in what was by then named Great Pond Plantation. Howard said most later settlers chose land beside the Great Pond; he surmised Belden chose a place farther north because he was settling without title and did not want the Kennebec Proprietors’ agents to find him.

Dowe and Howard agreed that the “township” was first surveyed in 1800, marking (preliminary) boundaries with Harlem (later China), Fairfax (later Albion), Davistown (later Montville) and Liberty. Howard dated the survey to August, 1800, and named the surveyor as William Davis, of Davistown. Apparently incorporation as a plantation followed.

(Dowe said the plantation was resurveyed in 1805; but since the lines were marked on “trees and cedar posts,” they tended to disappear, and boundary disputes, especially with Harlem and then China, persisted. In 1828, Dowe wrote, Palermo’s western boundary was permanently delineated and marked by a stone monument in Branch Mills [a village the two towns now share].)

Dowe found records of plantation meetings between 1801 and 1805, with elections of local officials and passage of local regulations. Howard added that the first, and only, clerk elected and re-elected was Enoch P. Huntoon, aged 25 in 1801, a doctor from Vermont who was one of the settlement’s “most respected citizens.”

Early in 1801, 56 men (including both Stephen Beldens) from “a place commonly called Sheepscot Great Pond Settlement” (no mention of a plantation) petitioned the Massachusetts legislature for incorporation as a town named Lisbon. Similar to the 1808 New Waterford petition mentioned last week, their document cited the “great difficulties and inconvenience from the want of schools and roads and many other public regulations very necessary for happiness and well being” that resulted from being distant from “any incorporated town.”

Dowe offered no explanation for the proposed name Lisbon.

Howard wrote that on Feb. 20, 1802, while the Sheepscot Great Pond petition was pending, the Maine town of Thompsonborough was authorized to change its name to Lisbon. He commented that for residents looking toward future greatness, “One way to get off to a good start was to borrow something of the grandeur of a foreign capital by using the name.”

With Lisbon already taken, Palermo, capital of Sicily, became a candidate; and, coincidentally, the popular plantation clerk’s full name was Enoch Palermo Huntoon, Howard wrote. “One wonders,” he added, “if…anyone…realized that Palermo, Sicily, had been one of the greatest, most cosmopolitan, cities in medieval Europe, and had a more impressive place in history than did their first choice.”

Dowe provided two other “legend only” accounts of the name Palermo.

The first story is of “a group of men…sitting around the stove at one of the local stores about 1804,” debating names. One of them pointed to the words on a box of lemons from Palermo, Sicily.

The second story says Sicilian Italians who had come “up the Sheepscot River to trap” camped near the lake and named their campsite “Palermo.”

The Massachusetts legislature approved incorporation of Palermo on June 23, 1804, Howard said. He and Dowe agreed the first town meeting was not until Jan. 9, 1805; neither explained the delay.

Main sources

Dowe, Milton E., History Town of Palermo Incorporated 1804 (1954).

Grow, Mary M., China Maine Bicentennial History including 1984 revisions (1984).

Howard, Millard, An Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine (second edition, December 2015).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Websites, miscellaneous.