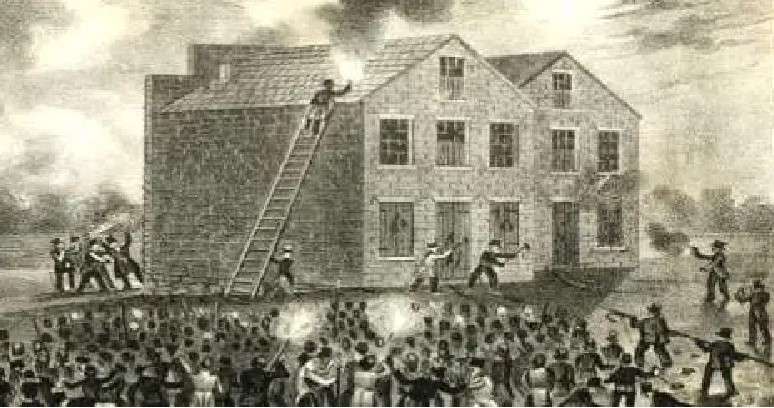

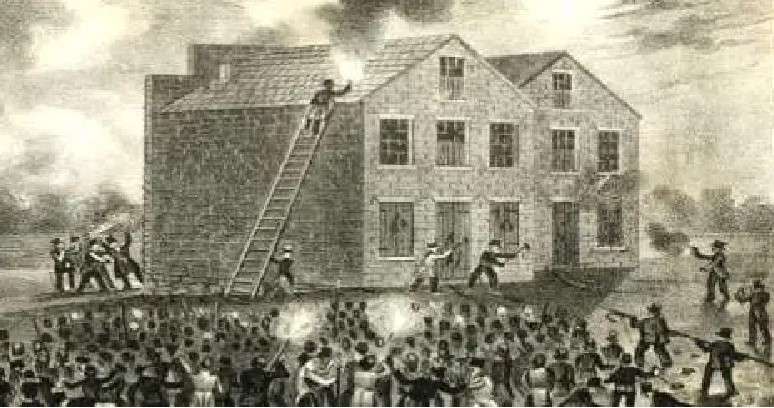

An 1837 engraving of the assault on Elijah Lovejoy’s printing company, in Alton, Illinois, where he was murdered for his anti-slavery beliefs.

Moving east from Winslow to Albion, that town has Lovejoy Pond, named after an early family who settled beside it.

Which family member came first is debated. Henry Kingsbury, in his Kennebec County history, named Rev. Daniel Lovejoy. Ruby Crosby Wiggin, in her history of Albion, said no, Daniel’s father, Francis Lovejoy, came first.

Francis Lovejoy was born in Andover, Massachusetts, in 1734. Wiggin wrote that he, his wife Mary (Bancroft), born in 1742, and their children came to Maine in 1790.

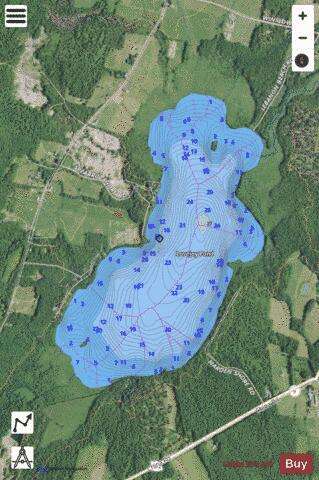

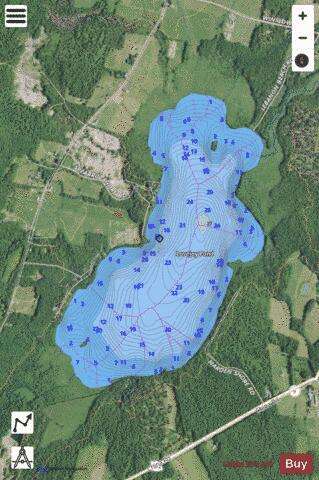

Lovejoy Pond

Francis left some of the family with his brother Abiel “on the Kennebec,” Wiggin said, while he cleared land for a cabin on the west shore of Fifteen-Mile Pond (Lovejoy Pond’s first name, reportedly because it was 15 miles from Fort Western).

Kingsbury included in his history an undated sketch map of the town of Fairfax (later Albion) showing “Rev D Lovejoy” – Francis and Mary’s son (see below) — owner of a rectangular lot on the west shore of the pond, near the south end.

(Your writer is sure the brother “on the Kennebec” was Captain Abiel Lovejoy, born Dec. 16, 1731, in Andover, and died July 4, 1811, in Sidney, Maine, according to Find a Grave. Alice Hammond’s 1992 history of Sidney includes an interesting summary of his life written by a descendant.)

Albion did not become Albion until February 1824. It started as Freetown Plantation in 1802, was renamed Fairfax in March 1804 and Lagonia (or Lygonia or other spellings) in March 1821.

Daniel Lovejoy was born March 31, 1776, in Amherst, New Hampshire, and died Aug. 11, or possibly Oct. 11, 1833. Wiggin said he was the youngest son of Francis and Mary’s four boys and three girls.

Daniel Lovejoy was a farmer and a Congregational minister. Wiggin listed him as one of three founders of the Congregational church in Albion in 1803.

When the Maine Missionary Society was founded in Hallowell in June 1807, Lovejoy was elected as one of its 52 new members, Wiggin said. He was also part of the Massachusetts Society for Propagating the Gospel.

Wiggin summarized a January 1808 trip for one – or both – of these groups that took him to Freedom, Unity, Burnham, Palmyra, Pittsfield and Vassalboro, among other places. She found that he was “licensed to preach” and later “ordained an evangelist” (no dates given).

From at least 1813, Lovejoy was clerk of the Albion church. In June 1829, Wiggin wrote, he “was installed as pastor” of four area churches, in Albion, Unity, Washington and Windsor. The Albion congregation built its first church in 1831-1832, meeting there for the first time Nov. 12, 1832. That meeting, Wiggin commented, was the last one that Lovejoy reported as clerk before he died.

He served in several town offices. Wiggin and Kingsbury said he was elected town clerk and town treasurer at Freetown Plantation’s first town meeting, held Saturday, Oct. 30, 1802, beginning at 10 a.m. They disagreed on how long he held each office – two or three terms as clerk and one or two as treasurer.

At a Monday, March 28, 1803, meeting, voters approved petitioning the Massachusetts General Court to incorporate “this plantation” with its current boundaries. They appointed Lovejoy to act as their agent in sending the petition.

In 1804, he was one of the three men on Fairfax’s first school board.

In January 1823 a Lagonia special town meeting appointed a five-man committee to petition the legislature – by then the Maine legislature in Portland – to rename the town Richmond. Daniel Lovejoy was on this committee, as was Joseph Cammet (see below), who, like Lovejoy, had been active in town affairs for years.

(The Town of Richmond, on the west bank of the Kennebec River south of Gardiner, was incorporated Feb. 10, 1823, and was named for Fort Richmond, built in 1719. Was Lagonia’s petition too late?)

On Sept. 20, 1801, in Albion, Daniel Lovejoy married Elizabeth Gordon Pattee, born Feb. 8, 1772, in Georgetown. This Elizabeth Pattee was not Ezekiel’s daughter Elizabeth, mentioned last week, who was born in 1777 and married Edmund Freeman. This one was a cousin of the younger one, daughter of Ezekiel’s youngest brother, Ebenezer (1739 or 1740-1825).

Daniel and Elizabeth Lovejoy had two daughters – they named the one born in 1815 Elizabeth Gordon – and either five or, probably, seven sons (sources disagree). Wiggin wrote that one son “died soon after birth,” one when three years old and one “as a very young man.”

Kingsbury wrote that Rev. Daniel Lovejoy “caused the greatest sensation the quiet community had ever known by hanging himself in his barn” in June 1833. Wiggin did not repeat this story.

Elijah Lovejoy

Daniel and Elizabeth’s most famous son was anti-slavery activist Elijah Parish Lovejoy (1802-1837). He was profiled in this series in the Aug. 13, 2020, issue of The Town Line.

Joseph Cammett Lovejoy (1805-1871; did Daniel choose the name to honor his local colleague? The revised spelling, Cammett instead of Cammet, is from Wikipedia) is summarized on Wikipedia as “clergyman, activist, and author.” Wiggin called him Reverend.

Wiggin wrote that Joseph graduated from Bowdoin College, Class of 1829. On Oct. 6, 1830, he married Sarah Elizabeth Moody (1806-1887 or 1888; sources differ), of Hallowell, at her family home in Hallowell.

An on-line source lists their 10 children, born between 1831 and 1852. The first four were born in Bangor and Orono, where an on-line report says Lovejoy was working with the Penobscots on Indian Island and may have started a school for them.

Wiggin found records of his service as a military chaplain for two months in the spring of 1839, during the 1838-1839 Aroostook War (see the March 17, 2022, issue of The Town Line).

His activism included abolitionism. He was a contributor to The Emancipator, started in 1833 by the American Anti-Slavery Society; and on-line sources list him as publisher of or contributor to the Hallowell-based anti-slavery paper Liberty Standard (1841-1848).

One of Joseph and Elizabeth’s sons was born in 1841 in Hallowell. Their last five children were born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Wiggin said Lovejoy was a pastor from 1843 to 1853. He was later a civil servant in Boston.

After the family moved to Massachusetts, Lovejoy became what Kingsbury called “an anti-prohibitionist,” as the temperance movement changed from moderation to prohibition (Maine’s prohibition law passed in 1851). Two of his pamphlets, found on line, are titled Prohibition Ground to Powder! (1869) and The Errors and Crimes of Prohibition (1871).

Lovejoy introduced the first pamphlet by saying that he had predicted the fiery debates over prohibition in a sermon 17 years earlier. Now, he wrote, he had “stood in that fire for seventeen years,…a long time to endure privation and abuse.”

He remained steadfast, he wrote, because “I told the truth in vindication of God’s word and Christ’s example; and in defence of the personal rights of every human being.”

Lovejoy began the 1871 pamphlet with a history of drinking, from the Assyrians (who, Lovejoy said, welcomed guests and honored their gods with wine) to Christ’s endorsement of wine. From this background, Lovejoy argued that the prohibitionists’ claim that alcohol was poison “is a broad and palpable falsehood.”

Prohibition was “founded on falsehood” and impossible to enforce, he continued. He called prohibitionists “guilty of great immorality”; and he said the execution of prohibition laws was “immoral and criminal.”

Wikipedia lists two biographies Lovejoy wrote. He and his younger brother Owen co-wrote and published in 1838 their Memoir of the Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy; Who Was Murdered in Defense of the Liberty of the Press, at Alton, Illinois, Nov. 7, 1837.

Joseph’s second book, Wikipedia says, was titled Memoir of Rev. Charles T. Torrey, Who Died in the Penitentiary of Maryland, Where He Was Confined for Showing Mercy to the Poor, published in Boston in 1847. Other sources say Torrey wrote it and call Lovejoy the editor or a contributor.

Joseph Lovejoy died in Cambridge in 1871; Sarah died in Boston in 1887 or 1888; both are buried in Cambridge.

Owen Lovejoy (1811-1864) worked on the family’s farm until he was 18 and then, with the family’s encouragement, spent three years (1830-1833) at Bowdoin College, though Wiggin said he did not graduate. He joined older brother Elijah, in Alton, Illinois, and was present when a pro-slavery mob killed Elijah and destroyed his printing press the night of Nov. 7, 1837.

Wiggin wrote that Owen Lovejoy studied theology in Alton and was a pastor in Princeton, Illinois, from 1838 to 1854. (Princeton is about 175 miles north of Alton and about 100 miles southwest of Chicago.)

Owen was an abolitionist and an Underground Railroad conductor in Illinois. He was elected a state legislator in 1854, and worked with his friend, Abraham Lincoln, to form the Illinois Republican Party. Elected to the U.S. Congress in the fall of 1856, he continued to represent Illinois from 1857 until his death.

Elijah’s youngest brother, John Ellingwood Lovejoy (1817-1891), was appointed by President Lincoln as U.S. consul in Peru; Wiggin said he served three and a half years. He moved to Iowa before 1843, if Find a Grave is correct in saying his four children were born there. Wiggin wrote that he “retired as a farmer.”

Find a Grave lists four family members buried in Albion’s Lovejoy cemetery; there are also unmarked fieldstones, the Town of Albion on-line site says. Marked graves are of Rev. Francis Lovejoy (Oct. 30, 1734-Oct. 12, 1818); his wife, Mary Bancroft Lovejoy (Aug. 2, 1742-May 8, 1792); Francis and Mary’s son, Rev. Daniel Lovejoy (March 31, 1776-Aug. 11, 1833); and Daniel and Elizabeth’s son, the first Owen Lovejoy (July 9, 1807-1810).

Several sources say this cemetery is on the west shore of Lovejoy Pond overlooking the water. A photograph on Find a Grave’s list of a dozen cemeteries in Albion confirms this information, showing a sign, gravestones and a pond; and your writer has driven past the cemetery sign on Pond Road.

The Town of Albion information on Lovejoy cemetery adds the cemetery is on South Vigue Shore Road. The map accompanying the information shows no cemetery near Lovejoy Pond.

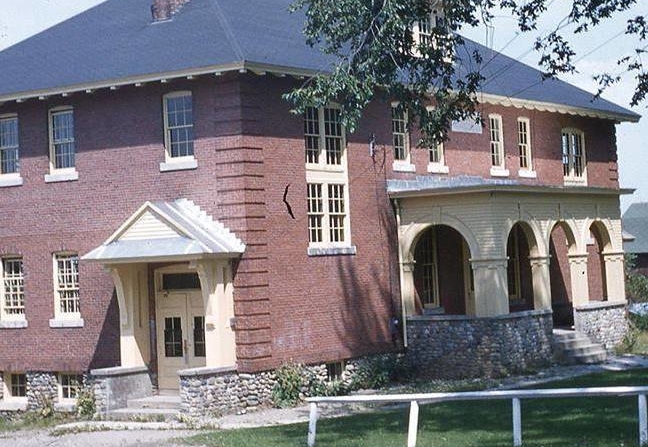

By the time Wiggin finished her history in 1964, Albion had put up a monument marking Elijah Lovejoy’s birthplace. Colby College, from which he graduated in 1826, had established the annual Elijah Parish Lovejoy Award (in 1952) and named a new building in his honor (in 1959). The college also maintains Albion’s Lovejoy cemetery.

(The June 11, 2020, issue of The Town Line has more information on this family and other early Albion residents, and – returning to a recent theme – a partial list of early dams and mills on Albion’s principal stream.)

Lovejoy Pond, in Albion, the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife says, covers 324 acres and has a maximum depth of 32 feet (as of 1997). The Lake Stewards of Maine site agrees on the depth and, as with Pattee Pond, reduces the size, to 279 acres.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Wiggin, Ruby Crosby, Albion on the Narrow Gauge (1964).

Websites, miscellaneous.

The University of New England, in Biddeford, has announced the following local students who achieved the dean’s list for the fall semester 2023:

The University of New England, in Biddeford, has announced the following local students who achieved the dean’s list for the fall semester 2023: