Hodgkins School

There are four school buildings in the central Kennebec Valley that are on the National Register of Historic Places, two in Augusta and one each in Winslow and Waterville.

Winslow’s Brick Schoolhouse has already been described, in the Jan. 28 issue of The Town Line. The old Cony High School, in Augusta, now the Cony Flatiron Building, will be a future subject.

This piece will describe Augusta’s Ella R. Hodgkins Intermediate School, later called Hodgkins Middle School, and the old Waterville High School, later the Gilman Street School.

The Hodgkins School served students in seventh and eighth grades (one source adds sixth grade) from 1958 to 2009. when the students were moved to a new high school building. The application for National Register status, prepared by Matthew Corbett, of Sutherland Conservation and Consulting, in Augusta, is dated Feb. 26, 2015. The building was added to the register the same year.

The former school, now called Hodgkins School Apartments on the Google map, is at 17 Malta Street, on a 20-acre lot in a residential neighborhood. Malta Street is on the east side of the Kennebec River, northeast of Cony Street and southeast of South Belfast Avenue (Route 105).

Originally designated the East Side Intermediate School, when the building was finished it was dedicated to former Augusta teacher Ella R. Hodgkins. She is listed in the 1917 annual report of the Augusta Board of Education as a Gorham Normal School graduate teaching at the Farrington School.

Corbett described the Hodgkins School as significant both for its architecture and because it was “associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history.”

Architecturally, he described the school as exemplifying the Modern Movement; it illustrated “the most recent trends in design and construction.” In terms of historical significance, Corbett wrote that the school was an element of “community planning and development, specifically the town-wide development of educational facilities.”

Augusta architects Bunker and Savage designed the “sprawling” building, Corbett wrote. It rose a single story above the ground and was almost 440 feet long, shaped like an E without a center bar.

The foundation was concrete blocks. The roof was flat; the windows Corbett called “aluminum ribbon sash and glass block.”

Both wings had full basements, giving them two useable floors, the lower partly below ground level, Corbett wrote. The boiler room and the shop classroom were attached on the northeast.

He described the arrangement of corridors, classrooms, offices, bathrooms and other spaces inside. The school had a combination gymnasium and cafeteria, with a stage, and an adjoining kitchen. The grounds provided space for a basketball court and softball and soccer fields.

In the 1950s, concrete blocks, aluminum and glass block windows were examples of modern materials, Corbett wrote. The Hodgkins School was also modern in its emphasis on “natural light and proper ventilation”; architectural drawings “included detailed ventilation and electrical specifications, large windows and skylights, as well as advanced mechanical systems for heating and cooling.”

Hodgkins was the third of three schools built during what Corbett said was “a decade long school building program that updated and consolidated Augusta’s schools to accommodate the post-World War II baby boom.”

He continued, “As the second intermediate school constructed in the city, the Hodgkins School represents the conclusion of the city’s effort to create modern elementary school buildings.”

The first two schools built under the city’s 1953 plan were Lillian Parks Hussey Elementary School (opened in September 1954) and Lou M. Buker Intermediate School (opened in September 1956).

While the Parks and Buker schools have been substantially altered, “The Ella R. Hodgkins Intermediate School retains historic integrity of location, design, setting, material, workmanship, feeling and association,” Corbett wrote.

* * * * * *

Old Waterville High School

Waterville’s Gilman Street School began life as a high school (Waterville’s second, Wikipedia says; the first was built in 1876). It became a junior high, then a technical college and is currently, like the Hodgkins School, an apartment building.

Gilman Street School was added to the National Register in 2010. The application by Amy Cole Ives and Melanie Smith, also of Sutherland Conservation and Consulting, is dated June 11, 2010.

The Maine Memory Network offers an on-line summary of the building’s history. Ives and Smith added details in their application.

The central block at 21 Gilman Street, facing south, was started in 1909 and finished in 1912 as Waterville High School. In 1936, a wing was added on the west side for manual arts classes; and in 1938-1939. a gymnasium and auditorium were added on the east side.

The last senior class graduated in 1963, and the building became Waterville Junior High School.

Meanwhile, Kennebec Valley Vocational Technical Institute (KVVTI), started in the (new) Waterville High School building with 35 students for the 1970-71 school year, rapidly expanded enrollment and course offerings. In 1977, KVVTI rented the Gilman Street building from the City of Waterville; the first courses were taught there in 1978, although some classes stayed at Waterville High School until 1983.

The Memory Network writer said that to save money, vocational students did some of the repairs and renovations the Gilman Street building needed.

KVVTI outgrew its new space, too, and by 1986 had completed the move to its current Fairfield location – a process that took six years, the Memory Network writer said.

The Gilman Street building housed educational offices and served other public and private purposes until Coastal Enterprises Inc. “in conjunction with a developers’ collaborative” turned it into an apartment building named Gilman Place. Its introductory open house was held May 11, 2011, as the first tenants moved in.

Ives and Smith said the original part of the building was designed by Freeman Funk and Wilcox, of Brookline, Massachusetts. The school is one of only a “few known examples of educational architecture” by that group, Wikipedia adds.

Ives and Smith called the school’s architecture “simplified collegiate gothic style.” All three sections are brick with cast stone trim.

The first building, Ives and Smith wrote, is a “symmetrical central three-story five-bay building.” The doors are in the two end bays; the central bays had windows on all three stories.

The doors described in 2010 “had Tudor gothic door surrounds with a four-centered pointed arch, white painted paneled intrados, and flush modern replacement doors with multi-light transoms.” Above each door is an arch over a stone sculpture: on the west, an eagle, wings spread wide, above the City of Waterville seal, and on the east an identical eagle above the Maine State seal.

Centered at the top of the building is a decorative stone rectangle with the words “Waterville High School.”

The 1930s additions were partly financed by the federal Works Progress Administration and were designed by Bunker and Savage of Augusta. Each wing is narrower and lower than the original building, and its front projects out slightly from the main building.

The exterior materials were chosen to match the original building, but Ives and Smith documented stylistic differences.

Of the west wing, they wrote, “Designed with more of the Art Deco influence of the 1920s-30s, the Manual Arts Building was simpler in massing and more streamlined in decoration than the original building.”

The east wing is more elaborate than the west. Ives’ and Smith’s description included a “substantial projecting stylized Tudor gothic tri-partite entrance,” framed by “cast stone quoins,” with its doors “recessed within gothic arched door surrounds” under “three original trios of four-over-six double hung lancet windows.”

They continued, “A cast-stone Tudor arch at the cornice level is elaborated by two round relief sculpture plaques of athletic themes (football and basketball) on either side; the arch fascia is infilled with fancy relief scrolls.”

In this wing, the combination gym and auditorium had an 84-by-68-foor basketball court in the middle; 15 “graduated rows of elevated seating” above the entrance in the south wall; and a 36-by-24-foot stage, with dressing rooms on each side, under a “painted wood Tudor gothic arch” along the north wall. “The aisle-end of each seating row is elaborately carved and painted art deco design,” Ives and Smith wrote.

Showers and locker rooms were in the basement below the stage.

Ives and Smith concluded that the Gilman Street School deserved National Register status for two reasons: its architecture, and its role in illustrating, with its 1930s additions, changes in education, specifically adding courses for non-college-bound students and accommodating increased enrollment.

They concluded, “[T]he property retains integrity of location, design, setting, material, workmanship, feeling and association and has a period of significance from 1909-1940.”

* * * * * *

For readers who wonder when this series will describe the district elementary schools that for years provided all the education many residents got, the answer is, “Not until the next writer takes over.”

The subject is much too complex for yours truly. Many local histories cover it, some writers basing their information on old town reports that contained detailed annual reports on each district.

Kingsbury wrote in his Kennebec County history that what is now Augusta was divided into eight school districts in 1787, 10 years before it separated from Hallowell. Eventually, he found, there were 27 districts.

The China bicentennial history has a map showing locations or presumed locations of schoolhouses in the town’s 22 districts. Sidney started with 10 districts in 1792; lost one to Belgrade in a 1799 boundary change; and by 1848 had 19, Alice Hammond wrote in her history of that town.

Millard Howard found detailed information on Palermo’s 17 districts for his “Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine”. Windsor’s highest number was 15 in 1866-67, according to C. Arlene Barton Gilbert’s chapter on education in Linwood Lowden’s town history.

The authors of the Fairfield bicentennial history didn’t even try to count theirs. Three paragraphs on pre-1966 elementary schools in town included this statement: “There were many divisions of the Town into districts for school management by agents” before state law changed the district system in 1893.

Alma Pierce Robbins summarized the difficulty of describing town primary schools in her Vassalboro history: “In 1839 the School Committee was directed to make a large plan of the twenty-two School Districts. They did, but it was of little value. The next year there were many changes and another school opened.”

Gilman Place

An undated, but recent, online piece by Developers Collaborative begins: “Gilman Place has structurally preserved and bestowed new life into a vacant neighborhood treasure, while repurposing it as affordable workforce housing for area families.”

The article says there are “35 affordable apartments in walking distance from the city’s award winning downtown. Gilman Place is an example of smart growth development simultaneously addressing two concerns many Waterville residents shared: how to preserve and reuse the former Gilman School as well as the need for more quality apartments in Waterville.”

Gilman Place won the 2011 Maine Preservation Honor Award, the piece says. It says state and federal tax credits helped the project, and quotes recently-retired City Manager Mike Roy calling the reuse of the building “one of the best success stories in the city in the last 25 years.”

Correction & Expansion of one of last week’s boxed items

The update on the First Amendment Museum should have said that it was 2015, not 1915, when Eugenie Gannet (Mrs. David Quist) and her sister Terry Gannett Hopkins bought the Gannett family home on State Street, in Augusta, that now houses the museum. The same wrong date was in the account of the Gannett printing and publishing businesses in the Nov. 12, 2020, issue of The Town Line.

The First Amendment Museum website says the Pat and John Gannett Family Foundation bought the building. The foundation is named for Eugenie’s and Terry’s parents, Patricia Randall Gannett and John Howard Gannett.

They met in Florida when he was assigned there as an Army lieutenant during World War II and married July 5, 1943. Patricia Gannett died Feb. 12, 2013, at the age of 91; John Gannett died July 16, 2020, at the age of 100.

[Editor’s Note: The online versions have been corrected.]

Main sources

Corbett, Matthew, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Ella R. Hodgkins Intermediate School, Feb. 26, 2015, supplied by the Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

Ives, Amy Cole, and Melanie Smith, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Waterville High School (former), June 11, 2010, supplied by the Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

Websites, miscellaneous.

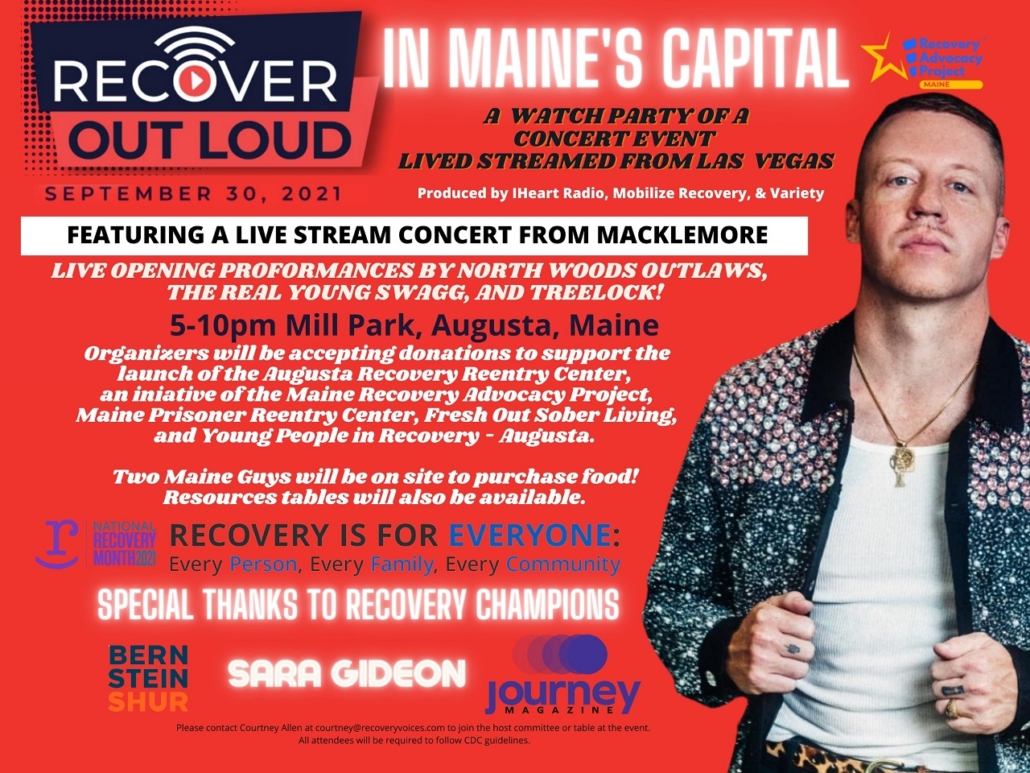

Join the Maine Recovery Advocacy Project as we Recover Out Loud in Maine’s Capital! and celebrate International Recovery Day and National Recovery Month on September 30th, 2021 from 5 to 10 pm in Mill Park!

Join the Maine Recovery Advocacy Project as we Recover Out Loud in Maine’s Capital! and celebrate International Recovery Day and National Recovery Month on September 30th, 2021 from 5 to 10 pm in Mill Park!

The following local residents were named to the 2021 spring semester dean’s list at Simmons University, in Boston, Massachusetts.

The following local residents were named to the 2021 spring semester dean’s list at Simmons University, in Boston, Massachusetts.

Big Brothers Big Sisters of Mid-Maine has received a generous $30,000 Innovation Grant from United Way of Kennebec Valley (UWKV) to help launch a new program linking local law enforcement one-to-one with Augusta youth. The new program, called Bigs with Badges, is a collaborative partnership matching students from Sylvio J. Gilbert Elementary School (Littles) with Augusta Police Department law enforcement and first responders (Bigs), in long-term relationships that support local kids facing adversity.

Big Brothers Big Sisters of Mid-Maine has received a generous $30,000 Innovation Grant from United Way of Kennebec Valley (UWKV) to help launch a new program linking local law enforcement one-to-one with Augusta youth. The new program, called Bigs with Badges, is a collaborative partnership matching students from Sylvio J. Gilbert Elementary School (Littles) with Augusta Police Department law enforcement and first responders (Bigs), in long-term relationships that support local kids facing adversity.